Last autumn, one of my friends was having dinner on the Row when the topic of conversation turned to post-grad plans. Someone mentioned doctorate programs, and before long, the whole table was debating the merits of a Ph.D. in a humanities field.

My friend was the only English major in attendance. The punchline of the story, as she later told it to me, was the following (real) quote: “Imagine making a contribution to the field of English. What do you do, invent a new contraction?”

That night, my friend laughed it off, forgoing any mention of just how many pages of reading it takes to pass an English Ph.D. qualifying exam, the number of words written in the average dissertation or the years of literary research necessary to “contribute to the field.”

But almost a full year later, the words are ringing in my ears.

Even though I’m pursuing a coterm from my bedroom in Pennsylvania, Stanford’s dismissive attitude toward the humanities occasionally feels as palpable as it did on campus during my time in undergrad. It felt especially so when I opened my inbox to find President Marc Tessier-Lavigne’s lengthy congratulations to Stanford’s Nobel Prize winners, economics professors Paul Milgrom and Robert Wilson.

Louise Glück, winner of the Nobel Prize in literature — and a visiting professor in the English department for a number of years — received no such recognition from the University. Over email and on Stanford’s official Instagram, our leadership consistently failed to acknowledge Louise Glück’s accomplishment, while devoting substantial virtual real estate to the economics prize.

While Glück is a visiting professor and not permanent faculty, she teaches students and works closely with other faculty members in the English department. I asked two English department administrators whether Glück herself had anything to do with the lack of official University attention, and while they were both unsure, they also pointed out that her role as visiting professor remains unchanged, and that she will be teaching at Stanford again this winter.

Somehow, I find it hard to believe that the University president would for any reason be barred from writing an email acknowledging a Stanford affiliate who won a prize that made international news. (Especially when the Nobel Prize’s official Twitter was permitted to publish the audio of this 7 a.m. phone call with the famed poet, which certainly rivals Milgrom and Wilson’s late-night doorbell video for entertainment value.)

Still, after a little over four years studying here, I can’t say I was surprised. My disappointment, however, was only compounded by the Stanford Flipside’s coverage of Glück’s award.

Don’t get me wrong — I love the Flipside. I’ve been a faithful reader since my freshman fall.

But their coverage of Glück saddened me, to say the least:

Could this be interpreted as a subtle mockery of Stanford culture, where very real conversations (as evidenced by my friend’s experience) essentially ask the question, “what the f— kind of Nobel Prize is literature?” Of course. It’s satire, after all.

But taken at face value, this “satire” falls flat. There was no such ridicule of the prize in economics, no supply-demand curve laden with expletives. Why not include some personal jabs at Milgrom and Wilson (with all due respect to those two professors)? Why center the sarcasm on the first American woman to win the Nobel prize for literature in 27 years?

Still, the Flipside’s coverage is a symptom of campus culture, not a cause (if there was anything I hoped to convey in my 2018-2019 opinions column). Now, as that culture moves online, I especially worry about the image the University is curating for its students, who are unable to experience the humanities-focused spaces normally available on campus.

We should be making an extra effort to celebrate our unique academic strengths while we are separated by geographic location and pandemic restrictions. And crucially, we should be setting an example for our incoming class, who are joining this institution for the first time and just beginning to explore what it has to offer.

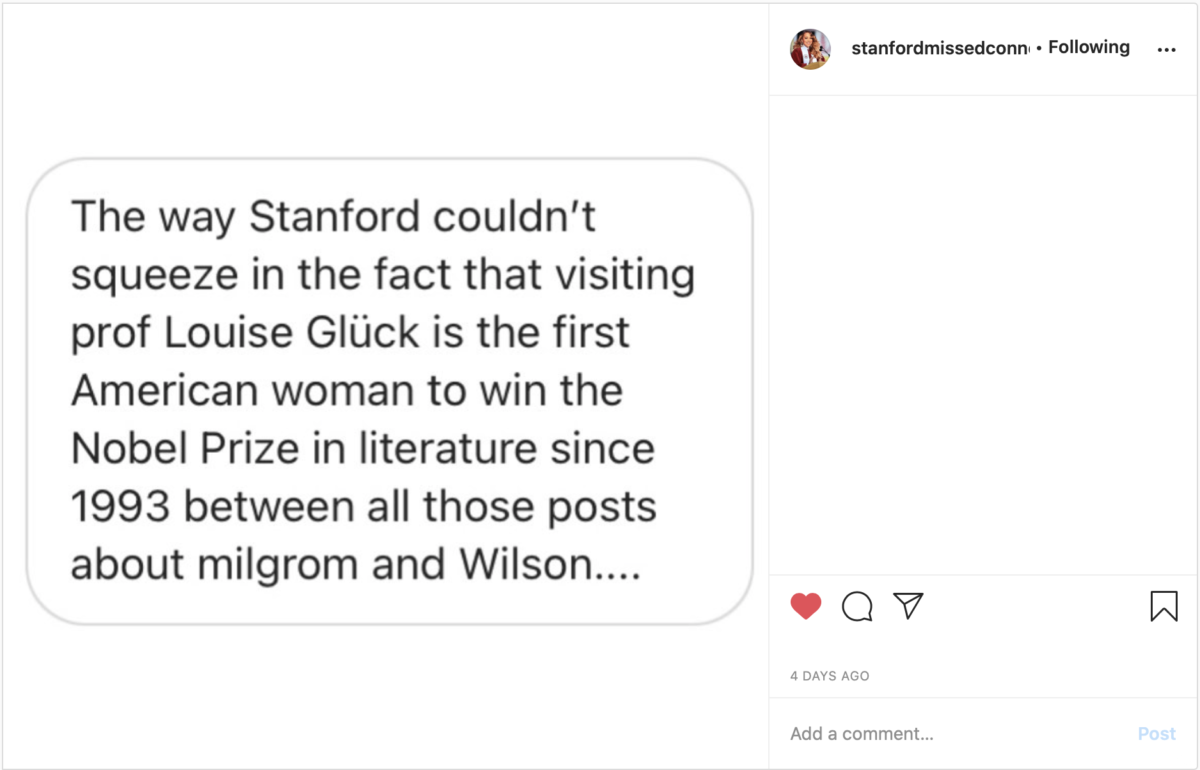

It does give me hope that some students were paying attention, as the Stanford meme page and Stanford Missed Connections Instagram can attest:

But even so, the fact that these posts had to be made at all is a loss. Undervaluing the humanities prevents students from studying those fields in the first place, and once they do choose that path, it wrongfully convinces them that their contributions are worth less.

I studied English and now I’m studying earth systems, with the hope that my future work will bring more people into the conversation around environmental solutions.

We need everyone, and if humanists have to waste time convincing themselves that their work matters, we lose out on their contributions. We lose the way poets can capture beauty in words; we lose the way artists use empathy to connect us; we lose advocates for justice and even just ordinary citizens who care about making the world a better place.

We need everyone, and that includes economists. But their perspective cannot be the only one. As our faculty continue to garner international acclaim, Stanford needs to set a better example — one of community, collaboration and acceptance.

Contact Melina Walling at mwalling ‘at’ stanford.edu.

The Daily is committed to publishing a diversity of op-eds and letters to the editor. We’d love to hear your thoughts. Email letters to the editor to eic ‘at’ stanforddaily.com and op-ed submissions to opinions ‘at’ stanforddaily.com.