Perhaps the worst fate of an insurance policy is the so-called “death spiral” — high premium costs lead to people dropping their coverage, and that smaller pool of enrollees pushes premiums even higher, fueling a self-sustaining loop. Graduate students say this is the current status of Vaden Health Center’s Dependent Health Insurance Plan (Dependent Plan), which provides coverage for dependent spouses and children.

Criticism resurfaced after Vaden announced on Monday that the Dependent Plan would see another round of increases in premium costs for the upcoming academic year. The hike, at between 12 and 15 percent from the last academic year, depending on how many dependents a student has, marks an increase of roughly 80 percent since 2013-14. Graduate students say that the increases aggravate already pronounced affordability and mental health challenges for graduate students at Stanford, and contribute to a less diverse campus.

“It’s unethical,” said Justine Modica, a fourth-year history Ph.D. student and a member of the Stanford Solidarity Network (SSN). “How is that okay for folks with families to be paying that for their kids, when their stipends aren’t going up at anywhere near the same rate?”

Modica and other graduate students — including representatives of SSN and the Student Parent Alliance — met with Vice Provost for Student Affairs (VPSA) Susie Brubaker-Cole, Vice Provost for Graduate Education (VPGE) Patricia Gumport and Graduate Life Office Director Ken Hsu on Thursday to express their concerns. Some students delivered personal testimonials about financial challenges and healthcare. Among them was Irán Román, a fifth-year Ph.D. student in music and neuroscience with a wife and a two-year-old child. Román and his family have faced severe affordability problems, which they say are compounded by healthcare costs.

“We are one ER visit away of being without food for almost two months,” he told attendees.

University officials say they are aware of the high cost of the Dependent Plan, and seeking more affordable alternatives.

“We care deeply about the concerns they shared with us, and we will continue to look for solutions to rising costs of dependent health care,” Brubaker-Cole and Gumport wrote in a joint statement to The Daily following the meeting.

Thursday’s meeting

Graduate students who attended the meeting asked for a reversal of the increase in premium costs, a moratorium on future increases to the Dependent Plan and the development of a long-term plan for full subsidization of healthcare coverage for children and spouses who cannot receive coverage through their employer. They maintain that the Dependent Plan’s high premiums are themselves responsible for the plan’s declining enrollment.

Brubaker-Cole and Gumport said that they are working to mitigate the plan’s high costs. In a statement to The Daily following the meeting, they said that the University has acted on a number of recommendations made in a report from the Student Families Working Advisory Group (SFWAG), and pointed to subsidies provided by the University that have prevented additional increases in Dependent Plan premiums.

In fact, next year’s 12.2 percent increase would have been 45.6 percent, if not for a $400,000 “one-time” subsidy provided by the Office of the VPSA, according to Brubaker-Cole and Gumport. This was the second consecutive year the University has provided a subsidy for the Plan. The previous one — a sum of $500,000 in “one time stop-gap funding” disbursed on the recommendation of SFWAG — was able to keep costs the same as the year before.

“We continue to be concerned that the current dependent plan is not sustainable,” Brubaker-Cole and Gumport wrote. “We are looking for alternatives that are more affordable.”

Before Monday’s announcements, there was uncertainty about whether the Dependent Plan would continue into the 2019-2020 academic year at all. SSN representatives attribute the program’s continuation and progress in improving affordability partly to advocacy efforts by their own group and the Student Parent Alliance, as well as the work of the Graduate Student Council (GSC).

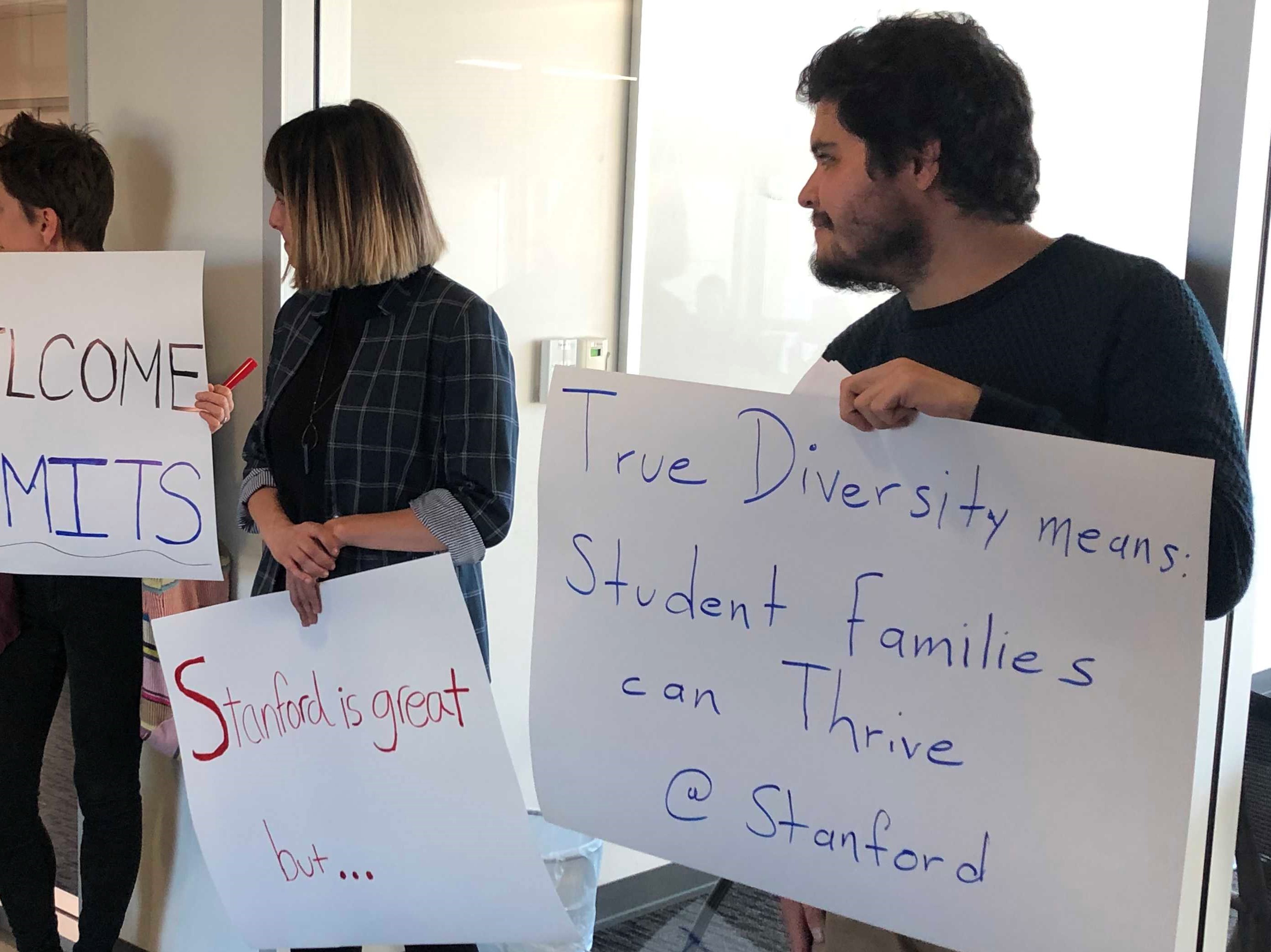

“We’ve been pushing,” said Dean Chahim, a fifth-year anthropology Ph.D. student and SSN member. Describing the increase as still “unacceptable,” Chahim called on graduate students to continue to advocate for improved affordability. Warning of the University’s alleged failure to address affordability, mental health and sexual violence issues, SSN representatives and others protested at an event on Friday for prospective and admitted graduate students from diverse backgrounds.

Chahim described alternatives to Stanford-subsidized healthcare such as Covered California, the state insurance marketplace and part of the Affordable Care Act, as largely inadequate, with high co-pays and deductibles.

“Basically people don’t get care at all,” he said. “They don’t go to doctors unless it’s an emergency.”

International students — who comprise 34 percent of the graduate student body — may be labelled as “public charges” if they enroll dependents on public insurance plans, which could harm their chances of receiving a green card, a prerequisite to citizenship. Affordability challenges may also be particularly acute for international students due to restrictions on their visas that limit their opportunities for additional employment, or keep their spouses from working at all.

“The University needs to make graduate education accessible to all — whether or not you have dependents,” Chahim said.

Students reported that University officials, while “sympathetic” to affordability concerns, would not reverse the increase, and made no new commitments to increasing the Dependent Plan’s affordability.

“We need more than knowing that they care,” Modica said. “We need money.”

Behind the numbers

While the announcement describes a hike of 12.2 percent, the increases in fact start at 12.2 percent (for coverage for a spouse) and climb to 15.0 percent (for coverage for multiple children).

Though a subsidy kept costs constant between the 2017-18 and 2018-19 academic years, next year’s increase continues a years-long trend. Relative to 2013-14, monthly premiums for graduate students with a spouse and multiple children will have increased by between 77.8 and 83.5 percent, depending on the type and number of dependents a student has. Since 2013, inflation has increased only by 7.8 percent, and the average family premium in the United States has risen by only 20 percent since 2013.

The current iteration of the Dependent Plan was rolled out in 2010 to mixed student reviews. Some criticized it as too expensive, others argued it was inferior to the Cardinal Care coverage students themselves can enroll in. A previous version of the Dependent Plan was discontinued in 2006 after it too fell into “death spiral” territory.

With the new policy, Vaden has tried to manage the costs of premiums by controlling enrollment: students can enroll a dependent only within 30 days of the start of their “academic career,” or after a “qualifying life event” like birth or marriage.

Vaden’s website says that the growing rates are necessitated by declining numbers of enrollees. Along with “robust utilization,” this shrinking pool has “caused costs to soar.” The University-sponsored health insurance option for students, Cardinal Care, has around 8,000 enrollees, whereas the Dependent Plan has a much smaller population of 389, according to figures from 2016-2017 academic year, the most recent data available. This makes the Plan “more vulnerable to spikes in utilization” than Cardinal Care, contributing to increased costs.

Peer institutions are grappling with similar issues, and have also seen increased premium costs for their graduate students with dependents. In 2017, healthcare coverage for dependents increased by 9.4 percent for dependents and 4.4 percent for students at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). The increase generated pushback from some graduate students, with one graduate student criticizing campus healthcare provider MIT Medical for “disproportionately” increasing insurance costs for families compared to “young, single students [who] tend to cost less than spouses that often have pregnancies or children that sometimes have complications which require expensive medical care to survive.”

MIT Medical responded with a statement denying that it had discriminated against families, and instead had kept rates for family coverage “artificially low” with subsidies.

With Vaden’s Dependent Plan, there is no evidence of intentional discrimination against graduate students with dependents because of supposed higher risk. However, Cardinal Care, the insurance option available to students, has consistently seen smaller rises in premium costs than the Dependent Plan. In the upcoming year, premiums will only increase by 7.4 percent as compared to the Dependent Plan’s increases of between 12.2 percent and 15.05 percent.

SSN representatives have urged Stanford to emulate peer schools like Yale or the California Institute of Technology (Caltech).

In the case of a married graduate student, Yale’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) provides half the cost of the two-person plan, resulting in an annual cost of $4,467 in 2018-2019 (less than the $4935.60 Stanford students pay in this academic year for 12 months of spousal coverage). Moreover, GSAS provides full coverage for all Ph.D. students and for their children under 26 years in age, who all receive coverage through Yale Health.

At Caltech, ensuring a single child costs $821 for each of the year’s three terms. With a $100 subsidy available per month per dependent, students pay $105.25 monthly, compared to Vaden’s $210.08 monthly premium this year. For graduate students living dollar to dollar, $105 a month makes a difference.

Beyond the numbers

Mateo Carrillo is a member of the GSC, and a sixth-year Latin American history Ph.D. candidate with a wife and two children. His family used the Dependent Plan in the 2013-14 academic year, when rates were far lower. Even still, to Carillo, this was not an indication of better quality care.

“I know of multiple grad student spouses who missed one payment and were immediately dropped by the provider,” he wrote in an email to The Daily. He cited this as an example of how the decline in Dependent Plan enrollment is “manufactured.”

“My impression of the insurance back then was that it was expensive, unnecessarily confusing to navigate and provided low quality service,” he wrote. “I can only imagine what it is like now.”

For Román, an international student on an F-1 visa, the “now” is not much better. Román delivered a testimonial at Thursday’s meeting about his family’s severe struggles with affordability and health care coverage. On his stipend, he supports his two-year-old child and his wife — who holds an F-2 visa that forbids her from working.

“Since I started the Ph.D., there has not been a single day that does not start with me checking our bank account,” his statement reads. “I wish I could say that we live paycheck to paycheck, but sometimes that’s not even possible, since after we moved to Family Housing my paychecks can be as low as $7 or $0 after Stanford deducts our rent payments.”

With funding from the Family Grant — a program that began this academic year — Román says he’s in a better financial position, with around $700 a month in after-rent income. Still, healthcare for his family remains a challenge.

“If I were to pay for my wife and child health insurance through Stanford, I would use $630, leaving us with $70 to buy food every month,” he said. While his child is covered through the Dependent Plan, his wife — having forgone health insurance for her first three years in the U.S. — now receives coverage through a private company.

With his current arrangement, he said, his family has around $290 per month for food, “as long as we don’t have to go to the doctor.”

Román also said that the coverage provided to his son through the Dependent Plan was inferior to his own Cardinal Care coverage. A trip to the emergency room cost was, for him, around $100. For his son’s December visit after a high fever, the cost was $444, creating extreme financial pressure. Román said that the University, given its financial records, can do a better job of ensuring students’ costs don’t become prohibitive.

“This is just a matter of someone grabbing some spreadsheet that I’m sure exists somewhere and realizing, ‘Okay, this is one student that is getting this [research assistantship] payment and they have two dependents and they’re going to probably live on family housing on campus,’” he said. “After you put all of that on that spreadsheet, you’re going to see that I’m going to be getting a $7 paycheck.”

To this end, Brubaker-Cole and Gumport reiterated in their email that the University will look into improving future plans for affordability measures, including the data acquisition process for formalizing collection and accessibility of data and resourcing data expansion.

In email correspondence between Gumport and Román, Gumport wrote that she was “extremely concerned” that Román lacked funds to cover his basic expenses, and described other University resources, including the Graduate Student Aid Fund, which covers the Campus Health Service Fee and students’ own Cardinal Care costs. She also described the Emergency Grant-in-Aid Fund, which she wrote “may provide funds beyond the publicized limit under certain circumstances,” though financial aid assistant dean and director Karen Cooper said in a recent interview that this fund was for “unanticipated emergencies,” not long-standing financial problems involving living expenses “that students are aware of before they come to campus.”

Gumport connected Román to Cooper and graduate and undergraduate studies assistant director Susan Weersing, who she said “stand ready” to assist Román and his family. Gumport added that she was “confident” that the Affordability Task Force would help address financial situations like his.

The challenges of the Dependent Plan

Many graduate students describes their affordability problems as a mere matter of math, with their stipends inadequate for covering these healthcare premiums on top of housing costs and living expenses.

Lisa Hummel, a third-year sociology Ph.D. student and a member of SSN and the Student Parent Alliance, has a partner who is a graduate student at another school.

“If I had her as my domestic partner and had her on the Stanford plan it would cost us $400 a month that we don’t have,” she said. “We currently live off of my graduate student stipend because she pays to be in her program.”

“In terms of having children, there’s no way that we can think about having a family in any sort of timeline that I’m here,” she added.

Carrie Townley Flores is a second-year Ph.D. student in Race, Inequality, and Language in Education (RILE) at the Graduate School of Education (GSE), who serves on the board of the Children’s Center of the Stanford Community and as the Family Chair of the GSE’s Student Guild.

In these capacities, she wrote in a testimonial delivered at Tuesday’s meeting, she hears “over and again stories of financial difficulty and financial stress among [graduate] students and postdocs with families.”

She also described her own circumstances. Her husband and her two sons depend on her for healthcare coverage. She pays $1,000 a month in healthcare costs — some of which goes toward her own coverage, which is not fully covered by her department. Along with childcare costs, rent, food and miscellaneous expenses, her basic necessities are around $7,000 a month.

“Increasing the cost of health insurance will only add to that burden,” she added.

In additional to doing research, taking courses, caring for children and working at their daycare, she wrote, she works an hourly job, and her husband works nights and weekends outside of his own full-time job.

“I understand how rising health care costs are putting pressure on Stanford — as they are putting pressure on everyone,” Townley Flores said. “But please consider other ways the system can absorb these costs without passing them along to grad student parents.”

Exacerbating issues of mental health and diversity

Graduate students connect the cost increase to broader issues at Stanford, including mental health diversity.

Chahim emphasized that the detrimental impact on students’ extends beyond their budgets.

“There’s many people who are suffering from this in silence, in isolated ways which only adds to the mental health burden that we’re talking about,” Chahim said. “One thing that came up over and over again in the meeting was the anxiety of this — trying to map out your future, trying to even just live day to day.”

Hummel said that the departments which don’t offer full subsidies of Cardinal Care coverage to their students are those which have “severe” mental health issues.

Graduate students also said that financial strain such as that imposed by healthcare costs has a detrimental impact on diversity, contributing to more narrow representation at Stanford.

“If we actually want to ensure that Stanford is a place where any student can go to pursue a Ph.D. … they need to make it affordable for students with families,” Modica said.

In the coming academic year, a graduate student with a spouse and two children will pay $893.69 per month, or $2681.07 per three-month quarter, for their dependents’ coverage. The minimum stipend for graduate students with a standard 50 percent research assistantship will be $10,956 per quarter.

“How does the math even work?” Modica asked. “Let alone if you need childcare for any reason. Childcare costs are astronomical.”

If she were an international student with two children and a spouse whose visa restricted their work opportunities, and she were deciding where she would do her degree, she said, “I can’t imagine saying that I would pursue it at Stanford.”

Contact Charlie Curnin at ccurnin ‘at’ stanford.edu and Elena Shao at eshao98 ‘at’ stanford.edu.