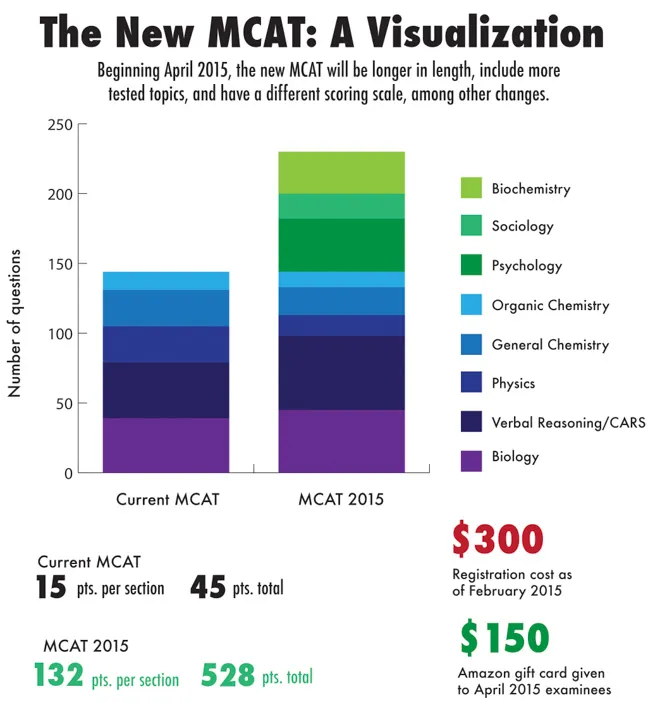

The revised version of the Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scheduled to be released this April will place greater emphasis on biochemistry and the social sciences.

The revised MCAT is a step towards a new and improved “premedical paradigm” that integrates scientific and social fields of study, said Stanford associate professor Donald Barr M.S. ’89, Ph.D. ’93.

According to pre-med advisor Yunny Yip, Stanford’s history of interdisciplinary cooperation may make it uniquely situated to help students meet the challenges of the new test and its underlying assumptions about what kinds of skills make the best doctors.

Changes to the MCAT include a new section on the psychological, social and biological factors that influence health, which is intended to emphasize concepts doctors need to know to understand and relate to a diverse group of patients. There’s also a greater focus on biochemistry, a field at the intersection of two disciplines.

For over a hundred years, admissions to medical schools have been based on the assumption that a prospective doctor’s performance in the natural sciences will accurately predict the quality of his or her professional practice.

“[That] turns out not to be supported by scientific evidence and in fact the scientific evidence questions that,” said Barr, who is trained in both medicine and sociology.

As an “unofficial advisor” to the writers of the new MCAT, Barr advocated a more holistic approach to premedical education—one that deals with biology, physics and chemistry as interrelated subjects, not as discrete fields. Barr also advocated for the inclusion of social science and humanities components like psychology and ethics.

Barr has implemented these ideas in his teaching at Stanford. Last quarter, he taught HUMBIO 165: Early Roots of Human Behavior, a class that considered the forces shaping human behavior beginning in childhood through the lenses of sociology, psychology and biology.

“You can take psychology, you can take sociology and you can take biology, and the theory is that you would get all the stuff that’s on the test. But it turns out you actually don’t get it all,” said Barr.

Despite this, Barr is the only professor so far who has taught a Stanford class that could be said to be designed to meet the needs of the new MCAT, says Yip.

She and her fellow advisors have been directing students to standard introductory psychology courses to prepare themselves for the test.

According to Yip, there is a great deal of breadth in the curriculum at Stanford compared to small liberal arts schools. She says that majors such as Human Biology incorporate various fields of science and sociology in a way that readies students for the test’s new approach.

“The diversity of courses that most students will have here will train our students well so they really have a strong foundation for the test and they don’t have to feel like they have a big gap,” said Yip.

She thinks, too, that students tend to come to Stanford looking for a broad education.

“Stanford is very interdisciplinary in its approach… Stanford students are adaptable, it’s the message you get when you first come here,” she said.

Many pre-med students don’t seem fazed by the changes – in fact, some welcome them.

“I think it’s very important for the premedical path…to branch out from just organic chemistry and chemistry and biology and physics to actual real life fields like psychology and biochemistry,” said Brian Levin ’16.

“In the future most of the medicine practice will be very much patient-centered, very much collaborative, so I think it’s very important to understand…in addition to the hard science skills, the sociological issues,” said Robin Cheng ’15, co-president of the Stanford Premedical Association.

Maheetha Bharadwaj ’16 took the old version of the MCAT last year but plans to take the revised one this spring, hoping for a better score this time.

“Taking the new one and studying for the new one will prepare me better to be a doctor because I’ll be learning those behavioral concepts, and I think that will be an asset,” Bharadwaj said.

And at the end of the day, though, Bharadwaj says it’s more important to her to learn from and be inspired by her classes than to study just what’s on any given exam.

“Honestly, it’s just a test, how much can you hate it and how much can you love it?” Bharadwaj said.

Contact Abigail Schott-Rosenfield at aschott ’at’ stanford.edu.