In the wake of the Campus Climate Survey report released last week, students and faculty have expressed concerns that the survey downplays the level of sexual assault students experience on campus.

Stand With Leah, a movement that seeks to change the way Stanford treats sexual assault survivors, responded with its own press release stating that the University “released numbers manipulated to minimize serious sexual violence at Stanford.”

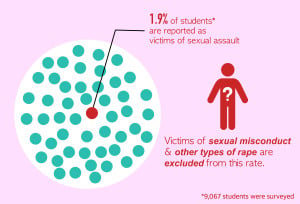

1.9 percent

At the heart of the controversy is Stanford’s reported 1.9 percent sexual assault rate – a far lower figure than Stanford’s peer institutions have reported.

The University arrived at this number by taking into consideration the individual percentage of every demographic – from undergraduate women to graduate men – and averaging them into one statistic.

Stand With Leah, however, holds that this number is “wholly misleading” precisely because averaging all the percentages downplays the fact that, in general, the rate of sexual violence against women is three to five times the rate against men.

The organization also found fault in the way that the survey was conducted. If students indicated that someone had performed a sexual act on them without their consent, respondents were then asked how the person had committed the offense. In order for the incident to be classified as “sexual assault,” the respondent had to indicate that he or she had been “asleep, unconscious, or unable to resist or respond,” that the offender had “threatened to physically harm [the respondent] or someone close to [the respondent]” or that force was used.

If a respondent only selected that they had been “drunk or high” without any of other three conditions, then the incident was classified as “sexual misconduct.” Stand With Leah asserted that this led to some survivors who had been incapacitated due to drugs or alcohol not realizing that they had to check multiple items for their incident to be considered “sexual assault.”

According to the Stand With Leah press release, which aggregated numbers from the survey data, 43.3 percent of fourth-year (senior) undergraduate women on campus experience either sexual assault or sexual misconduct – a figure that resembles rates at other top schools much more closely.

Stand With Leah co-creator Tessa Ormenyi ’14 explained that sexual assault and misconduct “affect women and gender diverse individuals disproportionately.”

“[The 1.9 percent statistic is] accurate but completely uninformative,” said Michele Dauber, a professor at the Stanford Law School who has also been involved in the past with Stand With Leah.

Dauber found the 1.9 percent to be counterproductive, giving students a false impression of how safe the Stanford campus is.

“The reason I care about this – there is a whole new group of freshman on campus, and their takeaway is that ‘I have a better chance of getting hit by lightning than getting raped…I don’t need to worry,’” Dauber said.

However, University spokesperson Lisa Lapin said averaged percentiles are appropriate for this kind of survey.

“Typically when you are summarizing a survey, you pick the numbers that are the aggregate and representative,” Lapin said.

Lapin maintained that the University was not emphasizing any single statistic and that it is not possible to provide all the pertinent figures in the first sentence of a press release.

“The 1.9 has been highlighted by the critics,” Lapin said. “The critics are giving more attention to that number than the University did.”

Survey methodology and definitions

Another area that has garnered criticism has been Stanford’s decision to forgo the Association of American Universities (AAU) survey in favor of creating its own, which uses a narrower definition of sexual assault.

The AAU survey – which has been utilized by Yale, Harvard and other peer institutions – defines sexual assault as unwanted behaviors such as touching and penetration carried out by force, threat of force or incapacitation.

“The definition that we used for the survey is the same definition that we use in our policies and it’s the same definition that is used for adjudication, and if a case were to go through the criminal justice system, it’s the same definition,” Lapin said. “The University decided it’s really optimal for everything to be consistent.”

For Ormenyi, however, internal consistency is not as important as the way the two terms are generally perceived. And their current perception is problematic:

“Sexual assault is really bad, and sexual misconduct not so bad,” Ormenyi said.

“Other schools did not use their states’ definition,” she added, citing other California institutions such as the University of Southern California and California Institute of Technology.

ASSU Executives John-Lancaster Finley ’16 and Brandon Hill ’16 also responded to the survey results with concerns about unclear definitions.

“[W]e believe there is a narrative of violence hidden underneath the data – as the blurred definitions of ‘misconduct’ and ‘assault’ helps create an illusion, one that is unnecessarily conducive to tolerance of unwanted sexual activity,” they wrote. “Sexual violence of all forms is a problem at Stanford, and one we are required to confront.”

But according to Lapin, the University included additional topics, such as perceptions of safety on campus, sense of community and types of sexist and homophobic behaviors, that the AAU survey did not cover.

“We ask many more questions than the AAU survey asked,” Lapin said. “[The University] designed a survey that was as extensive as possible and more extensive than the AAU [survey].”

Moving forward

Ormenyi explained that transparency is not the only issue. She said that there is also important information from the recent survey that was not released – including the percentage of women stalked and the percent by year of respondents who experienced penetration through incapacitation.

“The University should write a new report and include data that is missing and include full tables of which boxes were clicked when,” Ormenyi said.

Dauber wants the University to go one step further.

“One way we could double-check is to administer the AAU survey taken by Harvard and Yale and 25 other schools,” Dauber said.“We want to make sure we get it right.”

The University, however, stands firm behind the validity of its survey and the importance of the results.

“We had every expectation there would be people critical of the survey,” Lapin said. “We did the most thorough survey of any University.”

In their email sharing the survey results with the student body, President John Hennessey and Provost John Etchemendy Ph.D. ’82 emphasized that any percentage above zero of sexual assault is unacceptable.

“The results show clearly that we have much more work to do in battling sexual assault and sexual misconduct at Stanford,” the email read.

According to Lapin, there are no near-term efforts to re-administer the survey to the student body. But when another survey is once more administered to Stanford students, the results of this Climate Campus Survey will serve as the comparison point to address any trends about sexual violence on campus.

An earlier version of this article indicated that the in order for an incident to be classified as “sexual assault,” the survey respondent had to select both being “drunk or high” and “asleep, unconscious, or unable to resist or respond.” Being “drunk or high” was not a required condition for “sexual assault.” The 43.3 percent statistic also refers to fourth-year undergraduate women, not all undergraduate women. The Daily regrets these errors.

Contact Andrea Villa at acvilla ‘at’ stanford.edu.