When the movement organized by Fossil Free Stanford began its occupation of the space in Main Quad outside President John Hennessy’s office this Monday, it opened a new chapter in the long history of sit-ins at Stanford. Here are some of the major Stanford protest movements that have used the sit-in technique.

Draft exam

On May 19, 1966, 35 students began a sit-in at Stanford President J.E. Wallace Sterling’s office to protest Stanford’s cooperation with the Vietnam War draft. At the time, school campuses nationwide were being rocked by anti-war protests. Earlier in the year, on Jan. 31, 800 Stanford students joined the largest march in the University’s history after the U.S. resumed bombing in North Vietnam.

Sit-in participants criticized the University’s decision to host a draft deferment exam, which was slated to occur in two days. They argued that the exam was complicit in an unjust war and discriminated against minorities, the poor and the under-educated.

A subsequent handout clarifying the group’s motives also took issue with the administration’s unilateral approach to decision-making. Protesters claimed that, while the draft would profoundly affect student lives, neither students nor faculty had input in whether Stanford would host the exam.

Members of the sit-in said they would not leave the President’s office until they received “a meaningful reply from the administration,” and they settled in for the night with signs that read “I am just expendable” and “Uncle Sam just needs cannon fodder.” A Daily headline declared, “The office smelled of orange peels…”

The protesters voluntarily ended their sit-in after 50 hours, deciding that because the University refused to bargain with them, continued occupation would be unproductive. The draft deferment exam proceeded uninterrupted.

Nonetheless, a Daily article published at the time said that the protest “has been termed the most daring assertion of student rights in Stanford history.”

Military research and ROTC

Related tensions over Stanford’s role in the Vietnam War gave rise to new sit-ins four years later in 1969. Anti-war sentiment coalesced into the “April 3rd Movement” (A3M), which opposed military research at Stanford.

Starting April 11, 400 students held a nine-day-long sit-in at the Applied Electronics Laboratory, where most classified military research was done on campus. Within days, the Faculty Senate responded to student demands by banning classified research.

An April ASSU poll found that 93 percent of surveyed students believed the Electronics Lab sit-in “helped focus the attention of the University upon the nature of research conducted at Stanford.”

However, A3M continued to protest war-related work at the Stanford Research Institute, a University-affiliated innovation hub funded largely by the Department of Defense. On May 1, over 100 A3M protesters broke into Encina Hall in the middle of the night and occupied the building for seven hours before leaving to avoid arrest.

One year later, the “Off ROTC” movement staged an April 29 sit in at Old Union to protest the ROTC’s presence on campus.

Throughout planning for the sit in, Off ROTC struggled with internal rifts between proponents of nonviolent action and proponents of more militant activism. After police arrived to make arrests, the peaceful sit-in escalated into a violent four-hour clash between law enforcement and students: Protesters hurled rocks and police eventually deployed tear gas.

Off ROTC’s protests soon succeeded. In May and June, the Faculty Senate voted to end academic credit for ROTC and halt new enrollment in the program. The program did not become available again until 2011.

Hospital worker’s dismissal

In another demonstration that led to violence, the Black United Front (BUF) led a 30-hour sit-in at Stanford Hospital on April 7-8, 1971. Protesters demanded that the hospital reinstate Sam Bridges, a black janitor fired for allegedly not doing his job. They contended that there had been discrimination against Bridges.

The 60 sit-in participants used desks, chairs and filing cabinets to barricade doors against the police, who then smashed through a glass door with a battering ram and tried to use a Mace-like substance on protesters. Students countered with a firehose and flying projectiles. The police eventually overwhelmed the students with clubs, but only after two dozen protesters and 13 police officers were injured. The hospital sustained an estimated $100,000 in damage.

Later, police and students would both criticize each other’s use of force. Black Student Union co-chairman Mike Dawson ’72 raised issues of racism.

“Last year and earlier this year in massive student demonstrations by mostly white youths, there was not this type of police action in response,” Dawson said at a press conference.

Bridges lost an appeal to National Labor Relations Board and was not rehired.

Meanwhile, The Daily sued the police for breaking into its offices and searching for photos of the protests to identify protesters. The case rose all the way to the Supreme Court, which upheld the police’s right to search the newsroom with a warrant.

Divestment from apartheid South Africa

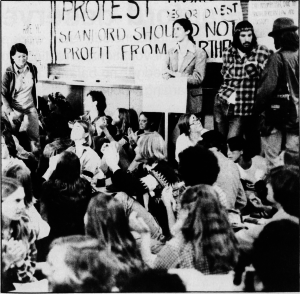

On May 9, 1977, over 500 students participated in a sit-in at Old Union demanding that Stanford divest from apartheid South Africa.

In particular, students were upset by the Board of Trustees’ recent decision not to leverage its stockholder status in Ford Motor Company and push the corporation to cut ties with South Africa.

The sit-in lasted five hours until police arrested 294 participants who refused to disperse. Over 500 supporters cheered for the participants and chanted their support for divestment as the protestors were led off to jail.

The next day, more than 300 students reoccupied Old Union following a 900-strong rally in White Plaza. As a second round of arrests loomed, the students grappled with whether or not to call off the sit-in. Just minutes before police were due to arrive, the protestors voted 180 to 135 to end their occupation. All students ultimately left the building, chanting “The people united will never be defeated” as they walked out the door.

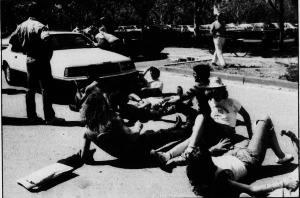

Protest over apartheid divestment renewed in May 1985 after the Board of Trustees said it would not fully divest from companies that invested in South Africa. Board members emerged from a morning meeting to find approximately 35 students laying down around their cars in protest, singing.

While Stanford never fully divested, it did successfully persuade Motorola, Inc. to step selling to the South African military and police.

Contact Hannah Knowles at hknowles ‘at’ stanford.edu.