Two years ago, Tom Camenzind ’16 was a sophomore at Stanford studying computer science. He had a 4.0 GPA and summer job offers from Facebook and Dropbox. According to him, his “medical history was a clean slate.”

Then, in January 2014, he contracted a respiratory infection from which he never fully recovered.

In February and March of the same year, Tom had enough energy to complete assignments and projects but often needed to rest in bed for a day or two to have enough energy for the next day. But after contracting a second cold in April 2014, his post-exertional malaise, characterized by extreme levels of fatigue following mental or physical exertion, began to worsen.

Since late August 2015, Tom has been unable to spend more than 30 minutes at a time out of bed. He spends most of the day in his bedroom, where the lights are always off and the blinds are drawn. When he’s ready for his three meals, he rings a pager button, whispers to his parents what he’d like to have and then eats in a chair beside his bed. His speech is limited to simple words that meet basic needs.

“It takes energy to listen, to comprehend and to respond,” his mother Dorothy Camenzind said. “But he does not even have that mental energy [to sustain normal conversation].”

Once a voracious reader, Tom Camenzind hasn’t been able to read for a whole year.

Camenzind, now on his second year of medical leave, is one of about 2.5 million Americans with severe Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, more commonly known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). According to Dorothy Camenzind, those afflicted with severe ME live in the “world of one room.” They experience “systemic exertion intolerance” and are also “sensory input intolerant.” The recovery rate for the disease is estimated at around 18 percent.

Despite the debilitating effects of ME/CFS on patients and their families, research on the illness has been historically underfunded. For decades, Dorothy Camenzind said, physicians have failed to recognize ME/CFS as a real disease, relegating it instead to a form of psychological or psychosomatic illness.

With inadequate institutional research funding, much about the disease remains a mystery — its molecular mechanisms have yet to be identified, and appropriate treatment options have yet to be developed.

Stanford’s Research Initiatives

The Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Research Center at Stanford is led by Ronald Davis, professor of biochemistry and genetics and director of the Stanford Genome Technology Center. The Center’s members include scientists, specialists and physicians across many disciplines, including Michael Snyder, chair of the Stanford Genetics Department, and Jennifer Frankovich M.F. ’05, M.S. ’09, director of the PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome) Program at the Stanford Children’s Hospital.

Davis claims the Center’s foremost goal is to identify molecular biomarkers for ME/CFS.

“The biggest problem really is that we don’t know enough [about the disease],” Davis said. “The way to solve that is to collect a lot of data. [The data] needs to be molecular data, not phenotypes. We have a lot of [phenotype] data; we know how people feel, what they can do and so forth. We need molecular data.”

In addition to searching for potential biomarkers, Davis’ research group will also study the roles of proteins, mycotoxins, heavy metals, cellular metabolites and the immune system in relation to ME/CFS.

“It’s very unlikely that we’ll find a single biomarker for the disease; it may be a combination,” Davis said. “We’ll pick those [biomarkers] out and actually test them on a large population, but we need to figure out what it is we need to look for. It’s going to involve looking at [and sequencing] the genome [and] looking at expression in the white blood cells.”

The research team’s current model proposes that ME/CFS results from a type of mitochondrial dysfunction.

“We’ve seen some evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in the metabolites,” Davis said. “You don’t see that in mitochondrial diseases, so it’s probably not a genetic effect. No one has seen this kind of defect before, but it’s something we have to continue to explore. It would explain everything [including the brain function and fatigue].”

“It would explain why those doctors are totally wrong when they say [to ME/CFS patients], ‘It’s all in your head,’” he added.

Previous obstacles in obtaining ME/CFS research funding

In March 2015, Davis submitted two grant proposals to the National Institute of Health (NIH) for funding to study patients severely affected by ME/CFS. Neither application was able to move past the NIH’s pre-proposal stage.

“They weren’t even sent out for review,” Davis said. “One of [the responses said we] should look at severe patients, but that’s what the grant was all about.”

Another response criticized the lack of data points in Davis’ proposal.

“They said we’re not making any neurological measurements like NMR scanning,” Davis said. “This is a proposal about severe patients that are bedridden. You can’t take them into the hospital and do a scan.”

The difficulties Davis and other world-renowned scientists have faced in obtaining funding for research initiatives on ME/CS reflect the overall lack of NIH-supported funding for the disease.

CFS has consistently ranked as one of the lowest NIH-funded diseases for the past five years. In 2014, the NIH devoted $5 million to ME/CFS research, a figure that amounts to less than $5 per patient. Comparatively, for the 1.2 million people living with AIDS in the United States, the NIH allocated over $2.9 billion dollars to HIV/AIDS research that same year, or about $2,482 per patient. Yet, physicians who treat both ME/CFS and HIV patients often agree that chronic fatigue syndrome is the more debilitating disease.

“The level of functional impairment in people who suffer from CFS is comparable to multiple sclerosis, AIDS, end-stage renal failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” said William Reeves, a former chief of the Viral Diseases Branch of the Center for Disease Control (CDC) in a 2006 press conference. “The disability is equivalent to that of some well-known, very severe medical conditions.”

Renewing focus

Fortunately, “the tide has turned,” Davis believes.

According to Davis, general understanding of the complexity and severity of ME/CFS has been furthered. He credits a comprehensive report created by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in February as “the major turning point of that tide.” The report, titled “Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness,” compiled research findings from virtually every CFS-related publication (approximately 9,000 in total) and proposed a detailed set of diagnostic criteria to enhance understanding of ME/CFS among the public, physicians and health care providers.

Two months ago, the NIH announced its plans to increase ME/CFS research in a news release detailing new actions by the institute.

“Of the many mysterious human illnesses that science has yet to unravel, ME/CFS has proven to be one of the most challenging,” said NIH director Francis S. Collins in the release. “I am hopeful that renewed research focus will lead us toward identifying the cause of this perplexing and debilitating disease so that new prevention and treatment strategies can be developed.”

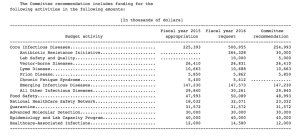

Further, in a budget agreement announced on Dec. 13, 2015, funding for the Centers for Disease Control’s CFS research program was restored to the full $5.4 million after being slashed to $0 by the U.S. House Committee on Appropriations last fall.

Personal perspectives on ME/CFS

These institutional initiatives to tackle chronic fatigue syndrome research have the potential to bring real change to ME/CFS patients, like Tom Camenzind and Davis’s own son, Whitney Dafoe.

“[Whitney] can’t communicate,” Davis said. “He can’t talk; he can’t read; he can’t write. He can’t listen to spoken words. He can’t look at something written. He can’t even look at letters. So I have to wear clothes that have no letters on them.”

Davis pointed at the black shoes he was wearing.

“See — this had ‘North Face’ on it. I had to grind it off because if [Whitney] saw that, if I walked in his room with that on [my shoes], he would try to interpret it, and that would exhaust him,” Davis said. “Basically, his brain is just on the very edge of surviving.”

Tom Camenzind’s condition has also continued to be severe.

“When he is at his sickest, he is unable to tolerate communication (verbal or nonverbal) or touch,” his mother said. “He hand-motions ‘leave me alone’ with a hand motion for me to leave the room. When he is slightly better, he can whisper some limited conversation, smiles, nonverbally manifests his humorous self and welcomes and reciprocates a warm hug.”

Dorothy Camenzind shared insight on the frustrations and challenges of finding therapies.

“Since he worsened shortly after starting both of the experimental medications that he tried this year, he now opts for no more experimental medications and is following the medical mantra ‘Do no harm,’” she said. “Tom’s and our hopes lie in current and future research — both into understanding the disease and evaluating treatments.”

With renewed focus on chronic fatigue syndrome by the NIH, increased CDC funding and strengthened public support, the hopes of ME/CFS patients like Tom are one step closer to being fulfilled.

“Our hopes and Tom’s hopes are that one day he will feel better, be able to participate in life and contribute to the world,” Dorothy Camenzind said.

Contact Katie Gu at katiegu ‘at’ stanford.edu.