Zombies and ghost ships and cats — oh my.

For the month of April, the Stanford Theatre will screen the films of legendary horror producer Val Lewton.

All nine of Lewton’s horror films will be screened in gorgeous 35mm film: “Cat People,” “I Walked with a Zombie,” “The Leopard Man,” “The Seventh Victim, “The Ghost Ship,” “The Curse of the Cat People,” “The Body Snatcher,” “Isle of the Dead” and “Bedlam.” “Bedlam” screens in a brand new 35mm print, prepared by the Library of Congress for this occasion.

Although David W. Packard, the stalwart owner of the Stanford, has screened Lewton’s movies in the past, this is the first time he will dedicate an entire retrospective to all nine Lewton horrors (or should we say, “terrors,” as Lewton preferred?)

Seventy years on, these masterworks of dread still chill the bones. Lewton, a Russian immigrant, took his melancholy with him on the boat to America. It infected his work when he was named the head of a B-movie horror unit at RKO Studios in 1942. There were only three rules: budgets of less than $150,000, running-times of less than 75 minutes, and rigid, lurid titles (“The Curse of the Cat People”) that couldn’t be changed. Otherwise, Lewton had free reign to make whatever movies he wanted.

Lewton could have made schlocky quickies — good money, but totally disposable products. He didn’t. Instead, in nine films in a space of only five years (the length of American involvement in World War II), he crafted a sad vision of a world crippled by gnawing loss, deep anguish, amnesia of history, amnesia of a dark past, and suicidal desperateness.

Lewton’s influences were wide-ranging: from Dostoevski to William Hogarth, from “Jane Eyre” to pulp porn. An unforgettable team of collaborators helped sustain his vision during the trying war years. The director Jacques Tourneur, with a pictorial feel for the unknown. The black actor Darby Jones as the zombie we walk with, the spirit of the slaves who stalk the sugar plantations. The French actress Simone Simon, the face of the displaced Eastern European, of repressed Woman.

Here’s my rundown of the five double-bills this April. All are essentials.

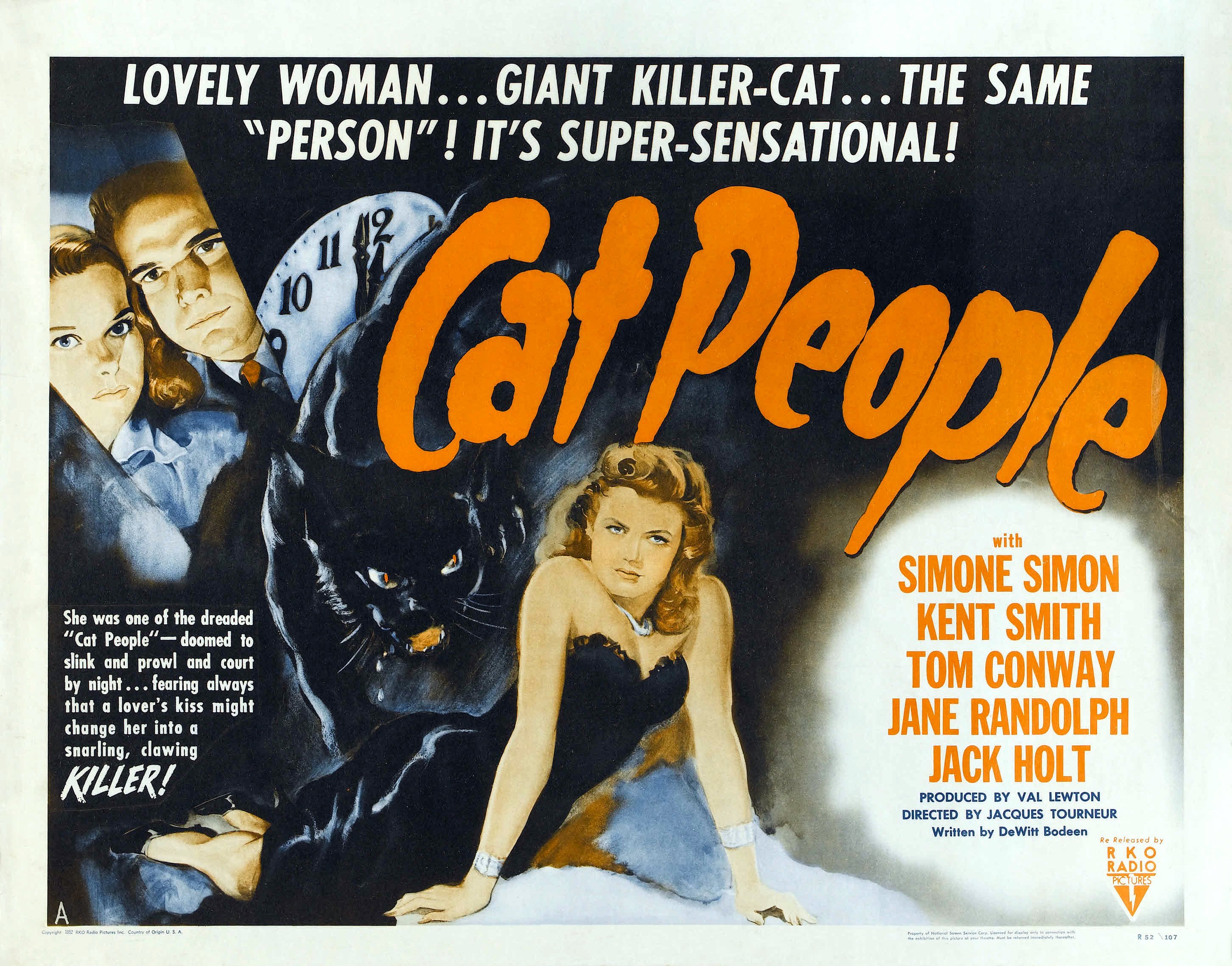

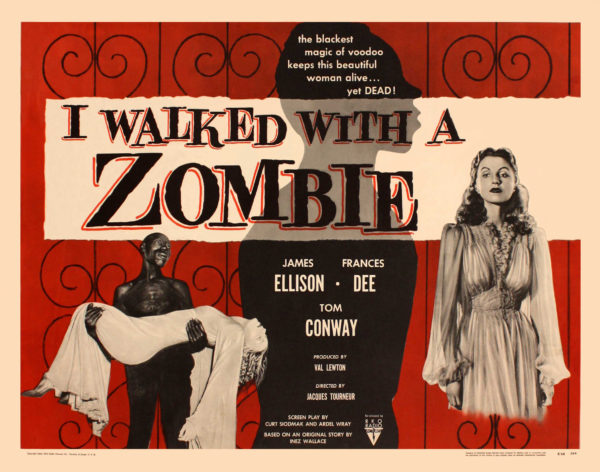

“Cat People” (1942)/”I Walked with a Zombie” (1943). The scary movie that started it all, and one of the greatest explorations of race, slavery and the loss left in the wake.

In “Cat People,” Simone Simon is a Serbian sketch-artist who refuses to consummate her marriage with a dashingly bland chap (Kent Smith); when she feels aroused, a condition in her bloodline makes her feel…rather catty? In “Zombie,” a Canadian nurse visits a sugar plantation island in the Caribbean, haunted by the history of slavery. She must cure the plantation owner’s mute wife, whose sickness may be a voodoo hex conjured up by the island’s slave descendants.

The best moments of “Cat People” (the beast’s growl morphs into a bus screech, running footsteps, spacey echoes in a rec pool) make up the entirety of “Zombie”: a hermetically sealed atmosphere of woe, tiny particles of terror packed together from various fears (social, psychological, racial, sexual). Lewton only suggests, even though we know what’s being suggested. We know “Cat People” is about sexual repression and ethnic homogenization; we know “Zombie” is about America’s hands stained with the blood of slavery. They are the skeletons in our closet — there and not there, acknowledged and yet ignored.

In both, the camera keeps needing to look away from the inexplicable horrors it shows. This can’t-look-away quality is courtesy of one of Hollywood’s great abstract directors, Jacques Tourneur. Like Vincente Minnelli, Tourneur fits into abstraction because he uses Hollywood plots as an excuse for deeper explorations into indefinite moods and emotions. Tourneur’s chief emotions — gloriously on display in “Zombie” and “Cat People” — are mania, oppression, empathy for outsiders who don’t fit the model of happy, healthy society.

“I Walked with a Zombie” plays Friday, March 31 through Sunday, April 2, at 7:30 p.m. — and 4:45 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. “Cat People” plays all three days at 6:05 p.m. and 8:50 p.m.

“The Leopard Man” (1943)/”The Seventh Victim” (1943). For me, these are Lewton’s two grisliest and depressing films — a stellar double-bill.

The New Mexican village of “The Leopard Man” is the site of a series of brutal serial murders against young Mexican women. There is a moment in this film — we only see seeping liquid beneath a door — that will shock you with its horrific poetry. Here, Lewton’s pet themes are in full effect: the focus on the marginalized edges of society, fetishizing the fear of the unseen, the bizarre appeal of the occult.

The latter is given its own 71-minute elaboration in “The Seventh Victim” — or, “The Big Sleep” if Bogie and Bacall were up against satanic cults. Choke-stuffed with too many twists to count on one hand, stuttering in and out of coherence, the characters are as lost as we are. When it starts, a schoolteacher is investigating the disappearance of her sister. When it ends, you simply won’t believe it. I still don’t. The ending literally sucked the breath out of me. I had to rewatch it three times on DVD, just to make sure my mind wasn’t playing jokes on me (it wasn’t) and Lewton was seriously suggesting what I thought (he was).

“The Seventh Victim” plays Friday, April 7 to Sunday, April 9 at 7:30 p.m. — and 4:45 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. “The Leopard Man” plays on all three days at 6:10 p.m. and 8:55 p.m.

“The Curse of the Cat People” (1944)/”The Ghost Ship” (1943). The moving sequel to “Cat People,” and the captain of a cruiser goes drunk with fascism.

“Cat People” was about feminine and ethnic repression; its daughter “Curse of the Cat People” is about the hallucinations of childhood. A little girl with an active imagination (Ann Carter in a spirited child performance) is visited by the ghost of her mother (Simone Simon of “Cat People”). It’s a story about a mother’s loss, the broken family, how grief pollutes the hopeful heart.

In “The Ghost Ship”, there is a hardening of arteries: wall-to-wall cruelty, the grisly smothering of a sailor with an anchor chain — and it only gets more hysterical from there. Though its title may seem to have no connection with the non-ghostly story, it does make a startling insight on the supernaturality of irrational power. We are reminded of this on the daily. The captain (Richard Dix) gets a thrill off killing people because his status and position guarantees no one will ever stop him. The desperateness of the positive ending only masks what we know is the real ending. This is only a movie. Out there, the Dixes rarely meet justice.

“The Curse of the Cat People” plays Friday, April 14 to Sunday, April 16 at 7:30 p.m. — and 4:50 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. “The Ghost Ship” plays on all three days at 6:10 p.m. and 8:50 p.m.

“The Body Snatcher” (1945)/”Isle of the Dead” (1945). Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster meet, and a plague spreads across a Greek island.

“Body Snatcher” stars the two giants of classic horror: Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff. I haven’t seen it, so I can’t speak for or against it. But come on: It’s Lewton.

He had the good sense to cast Karloff again in the apocalyptic “Isle of the Dead.” The situation is old yet always ripe: isolate some people in a remote setting away from civilization, tell them a plague is upon them, and watch them slowly turn against each other. Playing a Greek general guilty of unspeakable war crimes, Karloff is Frankenstein’s monster without the pathos — a chill in his heart — his untrusting face blocking access for those foolish optimists who try to read a hint of humanity in everyone. Martin Scorsese considers “Isle of the Dead” one of the eleven scariest films he’s ever seen: “There’s a moment in this Val Lewton picture that never fails to scare me. Let’s just say that it involves premature burial.”

“The Body Snatcher” plays Friday, April 21 through Sunday, April 23 at 7:30 p.m. — and at 4:35 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. “Isle of the Dead” plays on all three days at 6:05 p.m. and 9:00 p.m.

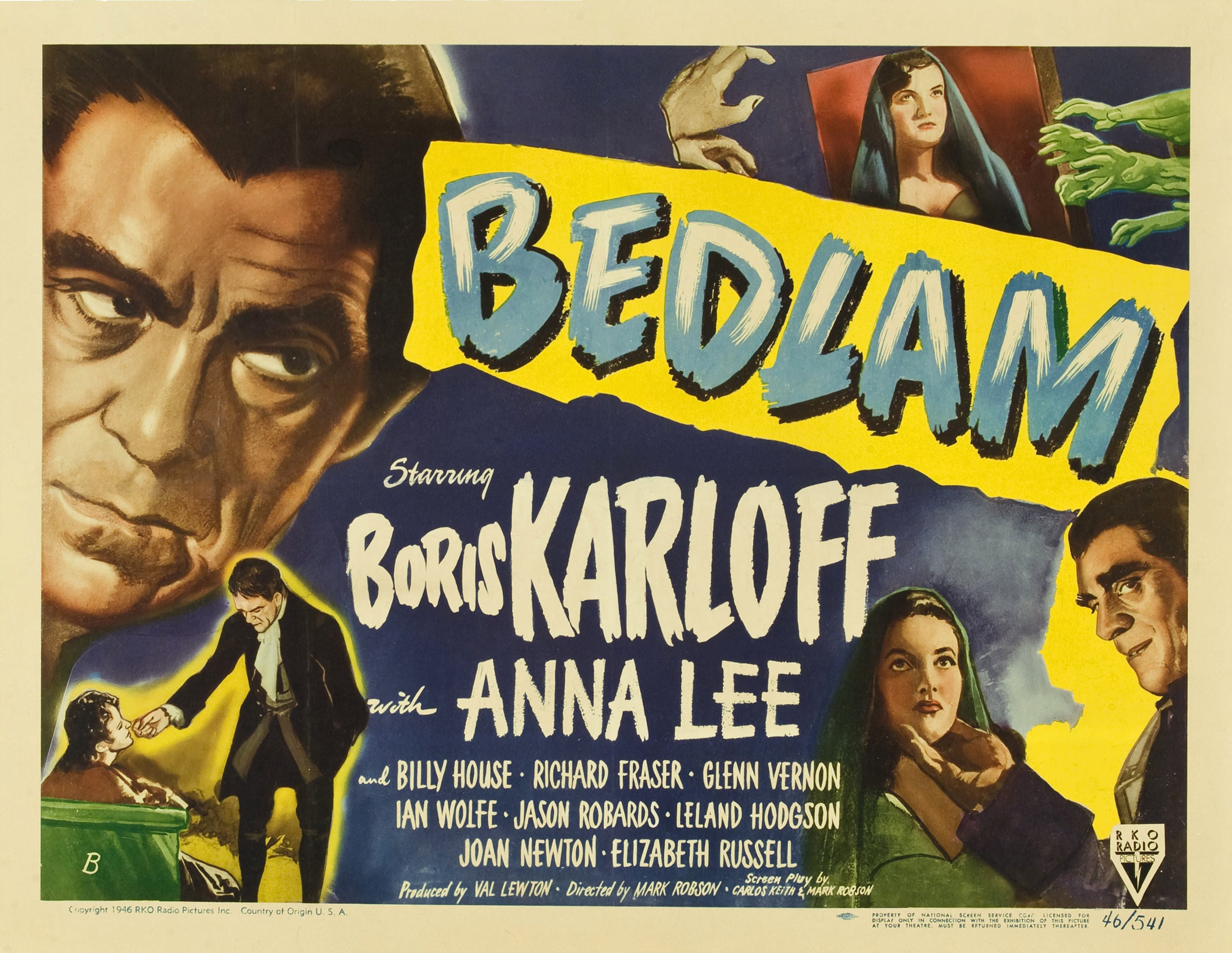

“Bedlam” (1946)/”The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952). The last of Lewton’s horror cycle, and Hollywood’s quasi-modernist tribute to the cycle’s greatness.

“Bedlam” features Boris Karloff in one of his greatest roles as Master Simms, the brutal head of the titular asylum. When the inhumane practices of Bedlam catch the attention of nurse/amateur sleuth Nell Bowen (Anna Lee), Master Simms kidnaps and commits her. It’s about the gap between theory and practice (can Nell the social crusader walk the walk?), female resistance to patriarchy, the blurring between real and nightmarish states, and (once again) a festering sense of a loss inside your gut that can’t be explained.

“The Bad and the Beautiful” (1952) is not a Lewton film; rather, it’s director Vincente Minnelli’s masterful tribute to artists like Lewton — and a fascinating glimpse at the Hollywood studio system during its own heyday. It’s a flashback yarn in three parts. Kirk Douglas is a washed-out producer who wants to get his three favorite people in the biz — a starlet (Lana Turner), a director (Barry Sullivan), and a screenwriter (Dick Powell) — together for one final film. They aren’t eager to work with such a brutal, manipulative and scheming cad. Each explain their side of the story — what a genius Kirk was, and what a monster.

Though it’s not a direct parallel to Lewton (he left directors like Tourneur alone to do their own business on set), one scene serves as a magnificent ode to Lewton. It’s when Kirk and Barry are trying to make the most out of a schlocky horror assignment (“Doom of the Cat Men”) neither of them want. Director Barry hates the Cat Man’s costume. But Kirk-as-Lewton comes up with an ingenious solution: don’t show the Cat Man. Barry asks, Will that work? Kirk responds, Of course it will. When Kirk gives Barry his reasons, he gives us the perfect epigram for Lewton’s cinema, and the weird, spooky phenomenon of watching movies:

“What scares the human race more than any other single thing? The dark. Why? Because the dark has a light of its own. All sorts of things come alive!”

“The Bad and the Beautiful” is one of the many great Minnelli films, but he would outdo himself 10 years later with the even-more-self-aware “Two Weeks in Another Town” (1962), a modernist snuff film of Classic Hollywood’s own suicide — and brief resurrection?

“Bedlam” plays Friday, April 28 to Sunday, April 30 at 7:30 p.m. — and 3:50 p.m. on Saturday and Sunday. “The Bad and the Beautiful” plays on all three days at 5:20 p.m. and 9:00 p.m.

For more on Lewton, I highly recommend Stanford professor Alexander Nemerov’s book on Val Lewton, “Icons of Grief: Val Lewton’s Home Front Pictures” (2003), where he analyzes with poet’s precision “I Walked with a Zombie,” “The Ghost Ship,” “Bedlam,” and “The Curse of the Cat People.”

Contact Carlos Valladares at cvall96 ‘at’ stanford.edu.