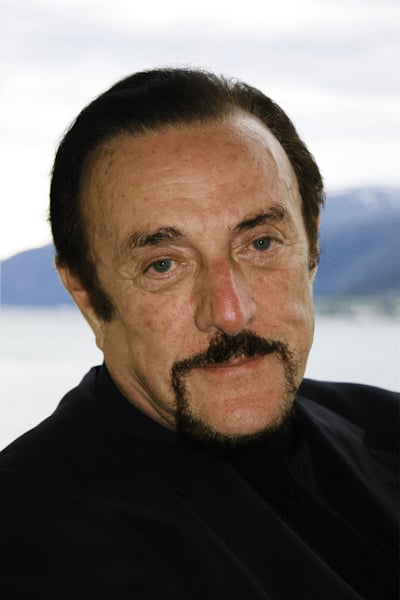

Philip Zimbardo, the psychologist best known for his Stanford Prison Experiment, died at 91 on Oct. 14.

Zimbardo’s legacy lives on through his research over five decades, spanning mind control, attitude change, heroism, deindividuation and time. His work frequently emphasized the role of the environment in shaping social behavior, a major contribution to the field of social psychology.

Zimbardo was raised in the Bronx, a borough of New York City, as the eldest of four siblings. Before leaving the East Coast for Stanford in 1968 — which would become his academic home for the rest of his life — he sought out education as a way to overcome poverty. After receiving his bachelor’s degree from Brooklyn College in psychology, sociology and anthropology and a doctorate degree from Yale in 1959, he pursued teaching. He taught psychology at Yale, New York University and Columbia. In 1968, he moved to the epicenter of creativity and innovation — Silicon Valley — to become a professor in psychology at Stanford.

Zimbardo and two of his graduate students, Craig Haney J.D. ’78 and Curtis Banks developed the Stanford Prison Experiment in 1971 to explore the effects of social situations on human behavior. The experiment assigned roles as either prisoners or guards to 24 consenting male participants for $15 a day. The prison, in the basement of the psychology building in Main Quad, consisted of three cells, guards’ quarters, an observation screen and an interview room.

Zimbardo hypothesized the environment would contribute to how the subjects reacted to situations, ultimately resulting in a hierarchy.

While Zimbardo instructed the guards to be tough on the prisoners, the participants never expected the post-traumatic stress they would experience for years to come. The experiment quickly descended into abuse toward the prisoners and intense hostility between the groups. The guards would search the prisoners, humiliate and verbally abuse them.

“The SPE serves as a cautionary tale of what might happen to any of us if we underestimate the extent to which the power of social roles and external pressures can influence our actions,” Zimbardo wrote in 2018, responding to persistent criticism of its methods.

Richard Yacco, a prisoner in the experiment, created an uprising among the prisoners against the treatment they endured.

“This was one week of my life when I was a teenager and yet here it is, 40 years later, and it’s still something that had enough of an impact on society that people are still interested in it,” Yacco told Stanford Magazine in 2011. “You never know what you’re going to get involved in that will turn out to be a defining moment in your life.”

The study was originally planned to last two weeks but ended after six days due to the psychological warfare the prisoners said they experienced at the hands of the guards.

Criticism and debate over the Stanford Prison Experiment have continued for decades ever since. Some commentators have even rejected it as a “fraud,” because researchers had instructed participants to act cruelly. The experiment is a continued case study in experimental ethics, as critics have called for psychology textbooks to omit the Stanford Prison Experiment from their curriculum.

In 1981, Zimbardo produced the documentary “Quiet Rage: The Stanford Prison Experiment” which details the methodology of the study and its findings. A 2015 film titled “The Stanford Prison Experiment” portrays the study through intense scenes of harassment, torture and prisoners in line-ups. Billy Crudup plays Zimbardo, the infamous psychologist.

Haney, now a psychology professor at UC Santa Cruz who was at the time a researcher on the project, remembers Zimbardo for his intellect and deep passion for psychology. Their interest in prisons and the situational dynamics within them sparked the project’s creation.

“I think Phil’s legacy will be as one of the most consequential social psychologists of our time, or any time,” Haney wrote in a statement to The Daily. “The core lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment, which he will be most remembered for, is at the very heart of the discipline of social psychology — that powerful situations have the capacity to significantly change the behavior and beliefs of persons who enter them.”

Zimbardo received 10 awards for his work in teaching, four awards in writing and 15 for his service work. In 2007, Stanford awarded Zimbardo with the Richard W. Lyman Award which recognizes outstanding faculty members. He retired from teaching in 2003 but continued to give lectures on his work.

“Phil was a truly phenomenal teacher and graduate mentor. In addition to his brilliance — he was a constant source of important ideas and insights — his enthusiasm for research was infectious,” Haney wrote. “You could not be around him for long without being inspired by him. It was a privilege to have been mentored by him.”

Ewart Thomas, emeritus professor of psychology, spoke highly of Zimbardo as a friend and colleague. In 1971, when the University was recruiting Thomas, Zimbardo interviewed him for a position in the psychology department. Thomas said Zimbardo’s warmth showed him that Stanford would be the perfect home for his teaching career.

“Phil’s Psych 1 course was so large that the supply of teaching assistants from the ranks of our graduate students was insufficient,” Thomas wrote to The Daily. “Phil’s innovation in the 1970s was to recruit a handful of talented and motivated undergraduates who had done well in the course and train them to be effective TAs.”

Thomas said the practice was so successful that it was adopted by other departments with large courses, such as human biology. Now, recruiting undergraduate students as TAs is standard practice because of Zimbardo, Thomas said.

Zimbardo is survived by his wife, Christina Maslach, three children and four grandchildren. Maslach was a pivotal part of ending the Stanford Prison Experiment. After witnessing the suffering the prisoners had endured, she told Zimbardo to end the study.

“I don’t know of anyone who loved the discipline of psychology more and who was more effective at spreading important psychological insights throughout the world to help make it a better place,” Haney wrote.