Often cited as one of the most influential studies in human behavior and social psychology, the Stanford Prison Experiment has spawned numerous films and cultural references over the past four decades. Just this past week, “The Stanford Prison Experiment,” a film based on the events of the study, had its world premiere at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah.

In conjunction with the film’s debut, The Stanford Daily caught up with members of the Stanford psychology department — including Philip Zimbardo, the lead researcher during the experiment and a current professor emeritus at Stanford — to learn more about the experiment and why the results of the study continue to remain relevant today.

Originally conducted in 1971, The Stanford Prison Experiment was designed to shed light on the underlying causes of abusive behavior in prisons. Professor Zimbardo planned a two week experiment in which he created a mock prison environment. In preparation for the experiment, Zimbardo sought out 24 male undergraduate student volunteers to be prison guards and prisoners and elected himself prison warden. Though Zimbardo supervised the subjects of the study, he did not interfere. The guards were allowed free rein to run the prison as they saw fit — so long as no physical harm came to the prisoners.

Within 36 hours of the start of the experiment, prison revolts broke out, and the guards began to institute sophisticated systems of punishment. Well-behaved prisoners were assigned to “privileged” rooms while the less subordinate were denied bathroom privileges. Soon, volunteers began to internalize their roles; one prisoner even begged for the termination of the experiment so that he might receive “parole.”

Though Zimbardo was forced to stop the experiment after only six days, his findings have become a permanent fixture in psychology textbooks and an inspiration for many artists. On the experiment’s cultural legacy, Bridgette Hard, Ph.D., Psychology 1 program coordinator at Stanford noted, “it’s a very, very old question to ask why people do bad things. The easy answer we usually come to is because bad people do bad things and good people do good things. But the Stanford Prison Experiment showed that people can be transformed and molded by the situation around them. Realizing that we can be so easily shaped in such a powerful way was eye-opening.”

In the years since the experiment, Zimbardo’s controversial methods have spawned several American films and documentaries — one of which was even scripted by Philip Zimbardo himself (available for purchase here) — while films such as “La Gabbia (The Cage)” and “Das Experiment (The Experiment)” have made the study known to foreign audiences. Even television series such as “Veronica Mars” and “Life” have aired episodes inspired by Zimbardo’s research.

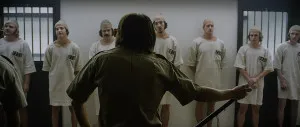

Now at Sundance, Kyle Patrick Alvarez’s film “The Stanford Prison Experiment,” which The Daily reviewed last week, features a historically accurate account of the now-infamous events that occurred in the basement of Jordan Hall. At the festival, Alvarez’s film won both the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award and the Alfred P. Sloan Feature Film prize, which is awarded to films for their outstanding depiction of science. To remain true to the experiment’s timeline, Alvarez recruited Zimbardo to serve as the main consultant to the film’s production, providing guidance on how the prisoners and guards were to be dressed and how the events of the film transpired.

The film’s inclusion in Sundance’s famed US Dramatic Competition line-up underscores the continued relevance of the Stanford Prison Experiment. Zimbardo notes, “I only realized afterward that the experiment had a message. It had a message that the general public needed to know about: You need to begin self-questioning. If you were in this situation, how would you have reacted? What kind of prisoner would you be? What kind of a guard would you be? Use these questions to think about your motivations and values.”

“The Stanford Prison Experiment” is currently in the process of finding distributors, and based on early reviews, it is well poised to shock movie-goers when it eventually hits theaters. Zimbardo, however, hopes the movie will act as a means of increasing empathy and compassion for people who commit contemptible acts. Hard agrees with Zimbardo. Each time she gives a lecture about the experiment she references the words of Martin Luther King Jr.: “There is some good in the worst of us and some evil in the best of us. When we discover this, we are less prone to hate our enemies.”

Since the conclusion of the experiment, Philip Zimbardo has been regarded as an expert on the effects of prison environments on guard and prisoner behavior, even testifying as an expert witness during the Abu Ghraib torture trials.

Contact Diana Le at dianale ‘at’ stanford.edu