The World Solar Challenge is held every two years and draws teams from around the globe to race solar-powered cars nearly 2,000 miles across Australia from Darwin to Adelaide. In the 2013 race, the Stanford Solar Car team acquired the prestigious title of “Best Undergraduate Team in the World” and fourth overall, and this year the team seeks to expand on those achievements with its new car, Arctan.

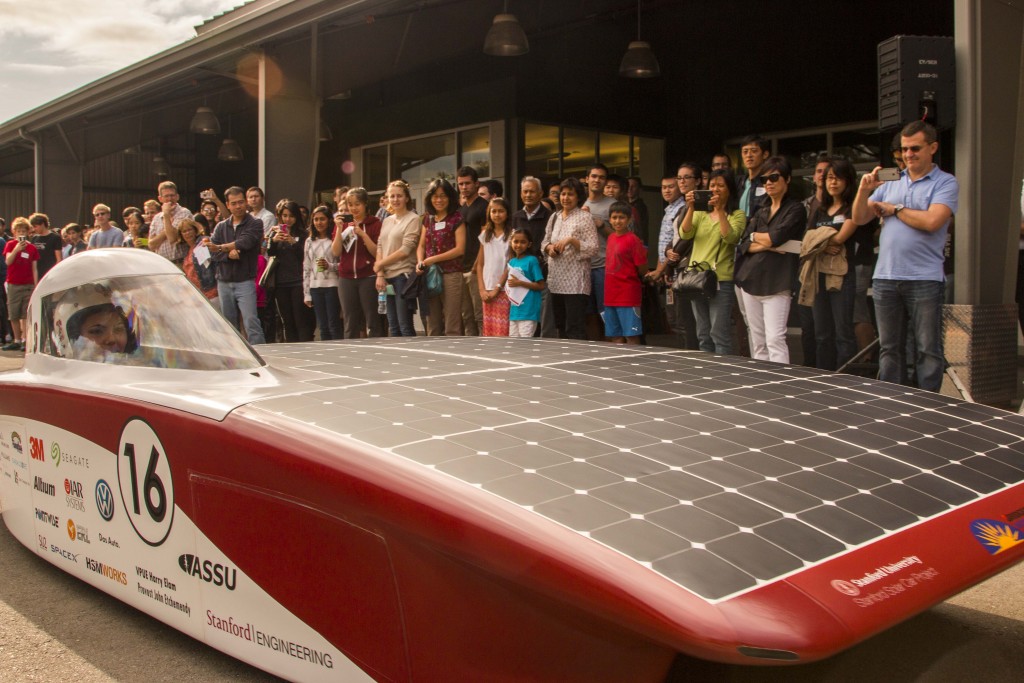

On July 10, Stanford Solar Car unveiled Arctan to the public. The event drew a diverse crowd from around the Bay Area to see the team’s new design for the 2015 fall race. For the rest of the summer, the team aims to fine-tune Arctan and prepare it for shipment to Australia.

A self-contained car

While an intense process by itself, the challenge of the competition comes not just from building the car, but from each season’s rule changes. The biggest rule change for this year’s race is the self-contained car requirement. The car cannot receive support from another auxiliary vehicle.

In the past, the team relied on a structure carried in a support vehicle to assist in flipping the car on its side to gather as much sun as possible during non-driving hours. Due to the new rule change, an immense amount of design work was necessary to allow Arctan to stand up and track the sun on its own.

According to team lead Guillermo Gomez ’16, the team also made a few additional changes.

“For one thing, the driver sits on the right side as opposed to sitting in the middle,” Gomez said. “The car is much thinner overall, and the top is much flatter and shorter to the ground. All these changes reduced the drag by 12 percent.”

The compartment for the driver is smaller than in previous years, and the driver’s legs sit next to the wheels. In addition, the car has a carbon fiber chassis built with the lightest technology available. It runs on about 1000 watts, depending on sunlight availability, acquired from six square meters of solar panels. That’s about the amount of energy it takes to use a toaster.

“Imagine trying to have your car run on that amount of energy,” said engineering lead Darren Chen ’16. “That is what makes this project so insanely difficult and such a great engineering exercise. We’re allowed so little energy that we have to make the most of it.”

This year’s season

Each new car is completed by the team working a non-stop cycle for two years. Solar car team members have worked in the lab every Monday, Wednesday and Saturday for the past year. After the rules were released in June 2014, it took half a year and 30 frantically working students to design Arctan throughout the summer of 2014 and the following school year. Fine-tuning will continue throughout the summer prior to the fall race.

Many team members said that the most exciting part of the season is the race in Australia. The team flies over in early September, accompanied by Arctan and extra supplies. This year, the race will take place on October 18-25.

“Overall, it’s just a blast,” Gomez said. “There’s no other way to put it – it’s an adventure. You’re driving out in the middle of nowhere in the outback, wilderness all around you – kangaroos, emus and so many beautiful landscapes.”

For Stanford’s team, the race typically takes four and a half days while driving from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. The car begins with a full battery of five kilowatt-hours and is driven until the end of the day or until the battery is empty.

“It’s basically like a big math problem – figuring out how much power you can spend,” Chen said. “Every day, over five days, you want to be curving down until you reach zero. If you’re driving too slow and consuming too little energy, you’re basically wasting power because you could have been going faster. If you overshoot it and you’re below zero, you’re sitting on the side of the road, and other teams are catching up.”

In order to manage this crucial power, the team has a whole fleet of vehicles that accompany their solar car. They include a scout car to examine conditions, a lead vehicle to warn pedestrian traffic and a chase car that connects to the solar car over wifi to determine its power usage.

“Being able to learn something inside of a classroom is one thing; passing a test is one thing,” Chen said. “But putting your name on the track and saying, ‘Look we have to build a car, and we’re trusting that we can put one of our friends or yourself inside of it and drive it down 3,000 km’ – that’s really putting your money where your mouth is.”

Contact Katie Mishra at 18kmishra ‘at’ castilleja.org.