He developed two pitchers to No. 1 selections in the MLB Draft over the last five years and has had 65 of his pitchers drafted over his last 20 seasons of coaching. He has mentored a pitching staff this season that has more than held its own and has been dominant at times, despite having 60.8 percent of innings pitched by the freshman pitchers entering Thursday.

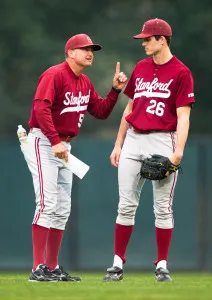

Stanford pitching coach Rusty Filter is no stranger to talent. But when you watch his former players excel as upperclassmen and in the big leagues, it’s easy to overlook the key role that he played in their ascents.

Filter is in his fifth season on the Farm after spending 21 combined years at San Diego State as a student-athlete and as an assistant coach. His San Diego State pitching staffs led the Mountain West Conference in ERA in six of the league’s first 10 seasons, and he has since built Stanford’s staff from both the recruiting and coaching standpoints. Still, of all his accolades, the ones that arguably stand out the most are the two No. 1 overall draft picks.

Both SDSU pitcher Stephen Strasburg and Mark Appel ’13 faced challenges and were doubted early on in their collegiate careers. Strasburg faced an uphill battle getting into strong physical shape during his freshman season and Appel had to overcome a taxing first year and develop new pitches in order to do so.

For Filter, the mental side of the game — building up the confidence and mental toughness of his student-athletes — was a large part of the coaching strategy for those two players and continues to be important with his young staff this season.

“Coach Filter is interesting. He works more on the mental side of the game than any other coach I’ve worked with,” said senior reliever A.J. Vanegas, who first spoke with Filter over the phone on a recruiting call while Filter was still coaching at SDSU. “He realizes we got here for a reason with our mechanics and doesn’t really touch that unless it’s a glaring problem. But he challenges you mentally to become the best player you can be.”

Strasburg — who was undrafted out of high school and arrived at San Diego State 30 pounds overweight in 2006 — by his own admission, “lacked a good mental game [entering college].” Filter and Strasburg’s other coaches challenged him mentally and physically to a point where he was ready to quit baseball entirely; the Washington Nationals would have had to find different Opening Day starters for the last two seasons.

“I never really lifted weights before [college], never really worked hard. I just had the ability to throw 90-92 raw, not really working at it,” Strasburg said. “It was extremely hard, especially my first semester with work outs — I was throwing up all the time — and I was really homesick too. So I was actually leaning towards quitting baseball altogether at the time. But I remember talking to [Filter] and having him work me through it.”

By the end of his freshman year, Strasburg was the Aztecs’ closer and had a limitless ceiling. He was considered in some circles to be the best pitching prospect in at least a decade, finally able to harness his natural ability. As a sophomore, he struck out a San Diego State-record 133 hitters, including one game in which he struck out 23. And in his junior year, he went 13-1 with a 1.45 ERA. That success could have been spurred by one meeting between Filter and the Aztec pitchers during Strasburg’s first year.

“He brought all the freshmen into the visitors’ locker room and he yelled at us like you wouldn’t believe. It was pretty scary,” Strasburg said. “He directly told me, ‘Everybody out there thinks you’re not good enough, thinks you’re too soft mentally, but you’re going to prove them wrong here.’ The fact that he had so much faith in me, despite really not having any sort of track record in college baseball, really hit home and made me feel like I was going to have a guy in my corner through thick and thin…He saw potential in me, he stuck with me, and I consider him to be a second father to me.”

“He brought the bulldog out of me. He wanted me to go out there and literally intimidate the heck out of the opponent,” Strasburg added. “Even if I gave up a few runs or if I struck out the side — especially closing — I was going to go out there and — excuse my French — be an asshole. It enabled me to go out there and let my natural ability work its way out there on the field.”

The mental strength that Filter instills in his pitchers comes from his own personal toughness. And some of that strength, and perhaps even a chip on his shoulder, was shaped during Filter’s childhood.

“One of the things that people don’t understand about him is that he’s very mentally strong. Our whole pitching staff feeds off of his mentality and intensity,” Vanegas said.

“Coach [Filter] would always give us stories of when he was a kid. He was the youngest of a number of brothers and he hung out with the older kids, wanting to fit in,” Appel said. “But his older brothers and all their friends kind of picked on him. He always sees that as an example of telling us where he came from and telling us the mentality that he had and how he’s kind of had to overcome being the little guy.”

Filter also challenges his student-athletes with his pitching strategy: getting ahead in counts and staying aggressive on the mound.

“Philosophy-wise, we’re aggressive by nature between the lines. We’re really going to push the envelope in everything that we do. And the strength side of it is really important to me — being fit to pitch,” Filter said. “The first thing is testing them a little bit physically and then understanding that we’re going to be a fastball-first program.”

Though the Cardinal do pride themselves in being able to command that fundamental pitch, Appel’s struggles in his freshman season — a 5.92 ERA in 38 innings out of the bullpen — mostly originated from having just one pitch: his fastball.

“People assume that he was a star coming in, but Mark didn’t pitch very well his freshman year,” said head coach Mark Marquess. “Then Coach Filter got to work with him and he really developed. [Appel] really grew under Coach Filter’s tutelage and coaching.”

In his senior season at Monte Vista High School in San Ramon, Calif., Appel was even removed from his team’s starting rotation and relegated to the bullpen in favor of other pitchers who were thought to be more talented. (Christian Jones, who went on to play for Oregon after high school, was one of those starters; he was selected just 551 picks after Appel in the 2013 MLB Draft.)

“He threw a lot of fastballs as a freshman because he couldn’t throw anything else for a strike,” Filter recalled. “But I had the data; I told him, ‘Mark, you have a great slider but you throw it for a strike 20 percent of the time. When the count goes 2-2, a number one is going down.’ He was frustrated with that and so he went out that summer and his goal was to come back with a changeup and have command with his slider.”

As they say, the rest was history, as Appel came back to The Farm after playing in the New England Collegiate Baseball League over the summer with a revamped collection of pitches in his repertoire. He won the Friday night starting job in the preseason and essentially held the job until his graduation. The two-time First Team All-American etched his name into the top 10 of nearly every statistical category in Stanford’s record book after a transformation that began in his freshman year and continued throughout his collegiate career.

“It was really all mental — the key stuff what I learned from [Coach Filter],” Appel said. “He’s a guy who’s seen a lot of really good players, he’s not impressed by talent and he’s a guy that respects hard work. He wants guys who don’t get too high on themselves when they pitch well, and also don’t get too down on themselves when they aren’t pitching well. He wants a guy that’ll go out and be a bulldog — who will go out and give seven, eight, or nine innings every time out.”

“I wasn’t that guy freshman year. I wanted to be that guy, but I wasn’t,” Appel added. “But through our conversations, what we worked on on the field, through understanding the game, understanding situations and understanding how to be a starting pitcher, I was able to work on those things both at school and at summer ball, knowing that the stuff I learned under Coach Filter helped me become a better pitcher.”

The Cardinal pitching staff this season has been made up predominantly by underclassmen, to such an extent that they sent out an unprecedented 27 consecutive first-year starters to begin the season. It goes without saying that the team misses Appel’s consistency and dominance in the rotation, especially having some of the toughest competition in the country in already having played six ranked teams.

“The schedule was a killer schedule — the people that we played this year. So the challenge was that they’re very young, and the concern that you have is that you throw them in the deep end and they can’t swim,” Marquess said. “They struggled earlier but they came through it and that’s a credit to him. Not only the mechanics, but the mental aspect too — and that’s critical with young pitchers.”

Cal Quantrill, Stanford’s first freshman Opening Day starter since Mike Mussina got the nod in 1988, has strongly improved after a tough couple of outings to begin the season. Over his last seven starts, Quantrill is 3-1 with a 1.64 ERA after going 0-2 with a 14.52 ERA in his first two starts.

Freshman Brett Hanewich has also been steady throughout the year, and boasts a 3.48 ERA over eight starts entering his Thursday appearance against Arizona State. Classmate Chris Viall, who began the season as the team’s Sunday starter, was roughed up in his last two starts but had previously held the Cardinal close in games against strong competition. But still, there’s room for development, which could be a scary thought for Stanford’s future opponents.

“They all pitched very well in the fall. The one thing is if you’re young or you’re fighting for a spot, you’ll have a tendency to try to throw the perfect pitch every time. And we’re kind of in that situation. We’ll get in trouble because we’re behind in counts or we give up free passes and things like that,” Filter said. “But the young guys have the ability. They have big arms, but they have the ability to throw secondary stuff for strikes. The future is bright any time you get a chance to return that number of quality guys on the mound.”

Regardless of how this season ends, the young Stanford pitching staff should be confident about its future, given Filter’s proven ability to personally connect with his players and develop their mental approaches.

“He’s someone who really cares about every pitcher — he really wants the best. He’s not going to beat around the bush, he’s going to give it to you straightforward — letting you know what you need to do to get better and get more playing time,” Appel said. “He’s somebody that really cares about each and every player that’s there and really wants the best for them and really wants to maximize their potential.”

Contact Jordan Wallach at jwallach ‘at’ stanford.edu.