About a month ago, the vice provost for student affairs Greg Boardman began the opening ceremony for the Windhover Contemplative Center with the following words:

“Reflect

Renew

Retreat

Replenish

Unplug

Breathe”

Boardman’s simple, elegant words reflect the architectural goals of the Windhover.

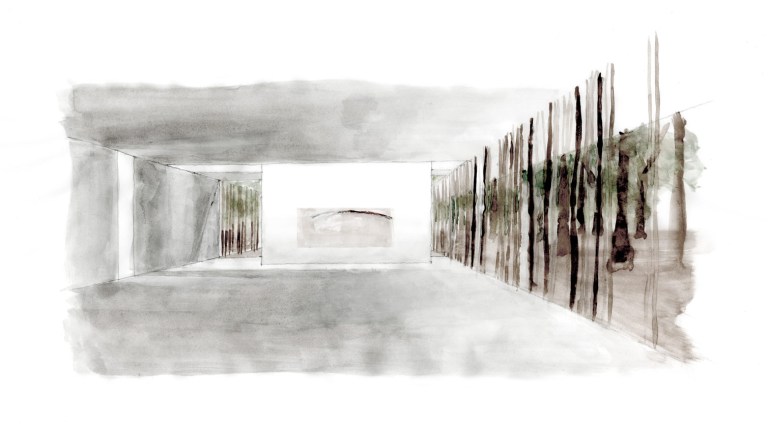

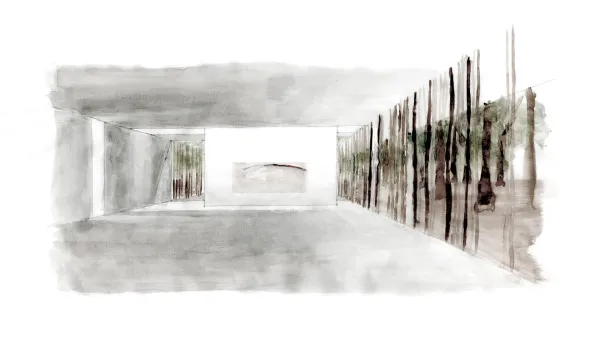

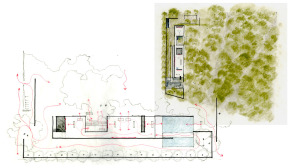

A retreat from the chaos of campus, for students and faculty, the Windhover Contemplative Center is designed to reflect the organic forms and soothing function of nature. Even from the preliminary drawings of the project’s architects – Joshua Aidlin and David Darling of Aidlin Darling Design – you can see that the firm intended to create a dialogue between the building and its surroundings — it doesn’t block the views of trees and natural life with opaque, solid walls. These drawings show the building as a horizontal swath of watercolor, drawing it into a geometric relationship to both the parallel ground plane and the perpendicular trees.

Wrapped mostly in glass, natural light illuminates the building during the day. In front of the glass stands a layer of thin wooden beams, creating a slightly obstructed view of the outside. Spread across the façade in an irregular manner, the tall wooden beams mimic the forms and distribution of the surrounding trees, bringing this language of verticality, irregularity and materiality to the interior of the building. Similarly, a courtyard on the north end of the building cuts into its rectilinear form, inviting the surrounding nature to permeate into the interior space.

The Windhover Contemplative Center’s relationship to the artwork inside is spot on. Created by Nathan Oliveira, a native to the Bay Area, the works are part of a series that examines birds as a subject and a metaphor. In the words of Oliveira himself, “the thing that was so wonderful about these birds is that they could soar so high in the sky, and they seemed to detached from our earth, and they seemed to only engage it when they had to.” In a similar manner, the building serves as a space that allows visitors to escape from the grounding demands of everyday life, and instead soar above these commitments mentally, emotionally and spiritually.

While the incorporation of art and nature into the space is largely organic at the Windhover, the building relies on non-local materials to reference Asian architectural aesthetics — the building is, after all, a center for meditation. But the bamboo, artificial ponds and smooth, grey stones used are unlikely to be found within a 100-mile radius, which detracts from the building’s otherwise powerful connection to its place in Northern California and its place at Stanford.

Although not without its faults, the Windhover Contemplative Center’s architectural connection with nature – instead of the sandstone, tile-roofed academic halls – allows us to remove ourselves from the stressful environments we have created on campus, and escape to a lofty, stress-free state where we can finally “unplug” and “breathe.”

Contact Mary Carole Overholt at mco95 ‘at’ stanford.edu.