Plagued by immediate concerns like the daily risk of caffeine overdose and that last problem on the midterm, few Stanford students stop to consider a more existential question: “What will be my legacy at Stanford?”

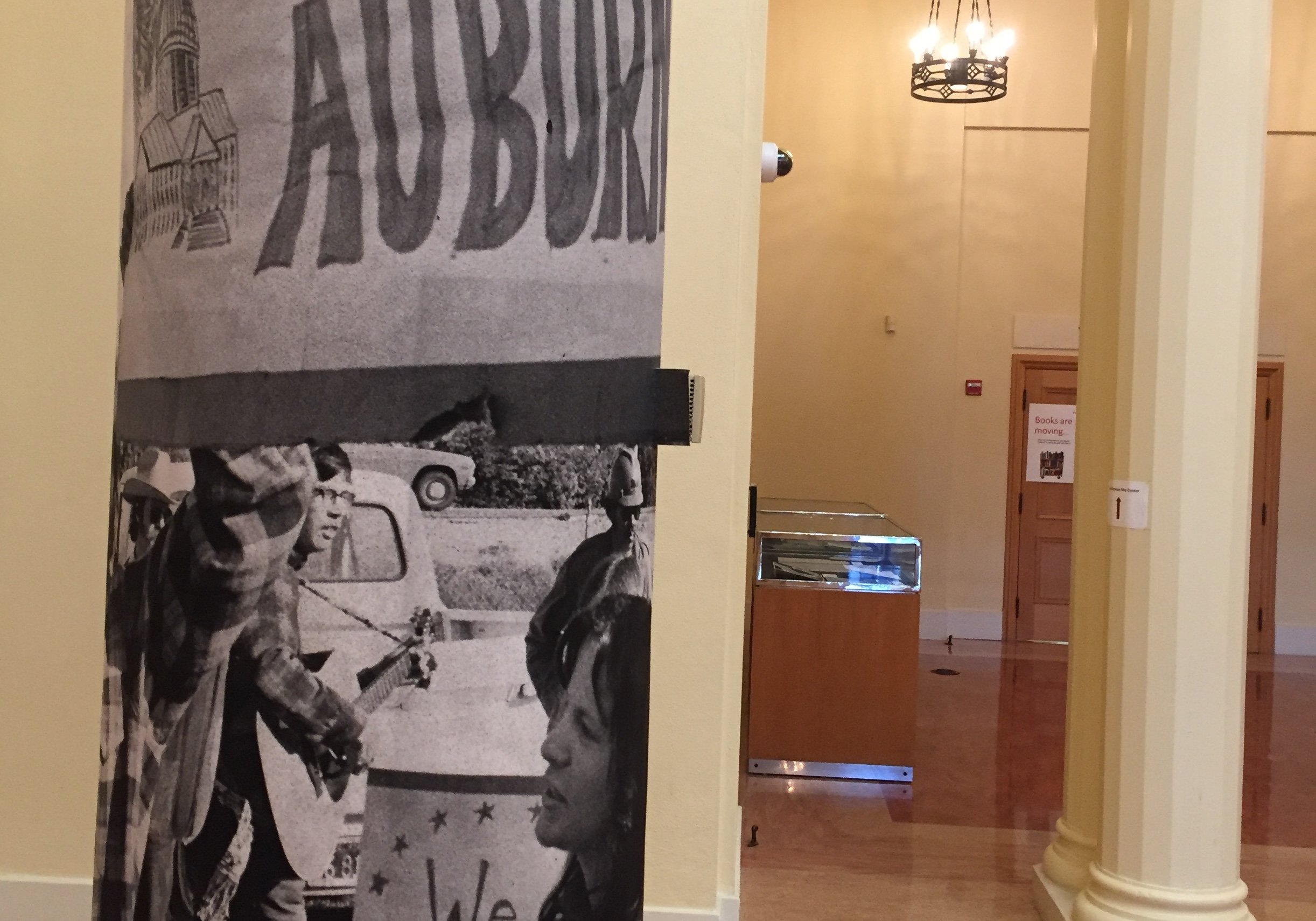

But every year, the graduating class Wacky Walks its way to Commencement — and risks exiting Stanford without leaving a trace. The University Archives address these questions of legacy and memory for students by piecing together the tangible items each class leaves behind, documenting student life across time. From Vietnam-era anti-war posters to photographs of the Fossil Free Stanford protest, the Archives aim to actively transcribe history as it unfolds in the present.

“We realized what we weren’t getting was students as they are here,” said Jenny Johnson, collections management and processing archivist. “When students are here, it’s an active time, and they’re not really reflecting as much. So, we’re really trying to get people to stop and think before they leave and graduate — are you just going to forget about all that stuff?”

Currently, archivists are expanding the depth and range of their materials on student group activism, especially those documenting the LGBTQ community, people of color and women. The move is motivated by both historical and present-day concerns: On the one hand, these minority groups have been underrepresented since the archive’s inception. On the other hand, archivists hope to give a voice to overlooked groups and underscore the impact of their activism amid the discriminatory political rhetoric today.

University Archivist Daniel Hartwig said that the initiative is an effort to promote diversity and inclusion by making sure student and faculty voices have a platform to be heard, given value and preserved. Without these voices, he pointed out, we lose stories that help us gain a broad perspective on what Stanford was really like at a particular moment in time.

For instance, archivists say that while Stanford has always had strong currents of student activism, the changes across time have also been significant.

“Things haven’t always been the way they are now,” Johnson said. “In many cases, students have changed the direction of the issues they care about.”

As such, archivists like Hartwig and Johnson are working to document this activism as it unfolds on campus in real time. They attend student group events such as the Inauguration Day and Dakota Pipeline protests as well as the Women’s March, and are constantly collecting materials from student groups.

The archives also serve an educational purpose. Building on the success of the “Stanford Stories” exhibit, which highlighted the civil rights history of Stanford, the University Archives are digitizing and cataloguing materials for research, teaching, learning and display in future exhibits.

“[It’s hard because] it’s what you with your lens think will be of historic significance, and then there are the things left behind that you don’t take,” Johnson said. “Odds are, if it’s important to a student now, it’ll be important to a researcher later.”

Resource-collecting versus memorializing

Some student groups have taken it upon themselves to engage in archival work in an effort to make future activism easier. In a similar project, Lily Zheng ’17 is in the midst of creating the Stanford Organizing/Archiving Resource (SOAR), which aims to be a digital archive of resources and materials for activists.

According to Zheng, who is also a Daily staffer, student activists often depend on the institutional knowledge passed down by their leadership — meaning that groups only last as long as leaders remain on campus. To centralize the materials that all groups can benefit from, Zheng began collecting materials from various student groups for an online archive that activists may access at the same link.

SOAR’s brand of archiving differs slightly in purpose from that of the University archivists. Initially, SOAR considered a partnership with the archivists, but according to Zheng and Schneider, the goals of the two projects diverge: Zheng hopes to guide future activists, while University archivists hope to capture student life more broadly.

According to Zheng, SOAR has the potential to engage with current students more effectively than the University Archives, which not all students may be aware of.

“The primary shortcoming of the archives at Stanford is that they’re not very accessible and very few students know about them,” Zheng said. “It doesn’t matter if you have perfect records of everything if no one knows that you have them.”

Her online resource guide will include digitized materials already present in the University Archives and collect them in one place for easy reference. In this sense, her work is less about memorializing objects — a poem or a photo of a protest, for instance — and instead attempts to make the the day-to-day practicalities of activist work less dependent on leaders who will leave in four years or fewer.

Archivist Josh Schneider explained that the University Archives have sought to make their materials more accessible by cataloguing all items donated by student groups and making them available in the library reading room or online. Each collection is carefully itemized on SearchWorks and the Online Archives of California.

Still, the differences in design between a project aiming to memorialize and one aiming to collect resources for present use reveal the archives’ different priorities. Josh Lappen ’17 of Fossil Free Stanford noted the importance of centralization and availability when it comes to activist knowledge. According to Lappen, while Fossil Free maintains its own comprehensive internal records, they are not necessarily well-organized or accessible to outside groups.

Fossil Free has donated to the Stanford archives in the past, but Lappen was not sure what the materials were, as the person who coordinated the donations has since left Stanford — representing the very knowledge vacuum that SOAR seeks to address.

Lappen and Zheng both said that the lack of publicly available activist history means that students rarely appreciate the past efforts that led to their present privilege.

“It can be hard in an atmosphere where activism isn’t visible to really mobilize the student body to realize this is an important use of their time and attention,” Lappen said. “I think that’s where having an unbroken record of activism on campus … can make a difference.”

In particular, Zheng highlighted that students today frequently dismiss the institutional memory held by administrators and professors. In the anti-University mindset of students, she said, there is little appreciation for the way these figures have watched and contributed to significant changes on campus.

“I think that memory is lost most of all because it’s not deemed important,” she said. “We need to change that. We need to create a culture that says, look, administrators, you can do something, and we’ll recognize it … Tenured professors, you’ve been here for so long, you don’t even have to be an activist, just write about what you’ve seen. What were things like in the last 30 years?”

Changing activism over time

Yet it is precisely the University Archives’ interest in Stanford history for its own sake that offers a unique perspective on activism in the longer view. By examining the parallels in student activism past and present, the Archives present an evolution of activism at Stanford.

Schneider noted that there have been several observable “periods of intense activism” in Stanford’s history, most notably during the Vietnam War. During this period, many students felt that their anti-war efforts were hopeless and would go to waste, a feeling that is not uncommon among protestors in today’s seemingly uncompromising political climate.

According to Schneider, the outcomes of history as recorded in the archives can show students that their activism has the potential to transform not only Stanford, but the world.

“[During the 60s], male students on campus actively burned their draft cards, [and] some went to jail,” Hartwig added. “Some [students were also] hopeless back then that they couldn’t do anything to end the war in Vietnam. I think there are some parallels for students today to examine what was successful then and what wasn’t successful and how that informs what they do today.”

However, constructing memories for the digital age presents its own set of difficulties. It may seem counterintuitive, but the digital materials that students produce nowadays are actually harder to preserve than paper materials due to hardware and software obsolescence.

“Someone hands us a scrapbook from 70 years ago, and as long as it’s not water damaged or moth ridden it’s good,” Johnson said. “But think about your digital materials from even ten years ago: Are they organized? Can you think about how to hand them off or describe them, or would we be able to read them?”

According to Hartwig, students rarely consider that technology may be impermanent. While the archives accept many forms of digital input, the reality is that texts, Facebook messages and Google docs may not persist — or at least not in a usable form. As the Class of 2017 begins to consider its legacy at Stanford, perhaps more paper and fewer emojis is the way to go.

Contact Ellie Bowen at ebowen ‘at’ stanford.edu and Fiona Kelliher at fionak ‘at’ stanford.edu.