Harold Pinter’s plays have their charms, but they aren’t for everyone. They have a tendency to be abstruse and dialogue-heavy but place a lot of emphasis on what isn’t said, sometimes referred to as the “Pinter pause.” The San Francisco Shorenstein Hays Nederlander (SHN) production of Pinter’s first commercial success, “The Caretaker,” is no exception: it’s a faithful adaptation that will be sure to please Pinter fans but may be inaccessible to the casual viewer.

As “The Caretaker” opens, Aston (Alan Cox), the resident of the flat, brings home Davies (Jonathan Pryce), a hoary vagrant, after rescuing him from a bar fight. Aston offers to share his flat with Davies while he gets back up on his feet. Eventually, we meet Aston’s younger brother, Mick, who owns the building and the flat. Here, the two brothers both offer Davies employment as the caretaker of the building, inciting Davies to ingratiate himself with each, shifting his alliances throughout the play for strategic gain.

“The Caretaker” is like Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” meets Anton Chekhov’s “The Seagull”: a cross between the theatre of the absurd and satirical realism. There are three characters–Aston, Davies and Mick–each pathetic in their own ways, tragically comedic and paralyzed. The characters are confined to a dank, dilapidated, cluttered attic apartment in London for the duration of the play. Like Vladimir and Estragon in “Godot,” Pinter’s characters are always talking idly about leaving to do great things but never actually do, concocting increasingly flimsy reasons to stay put.

Davies’s excuse for inaction is his need for a new pair of shoes to take him places. While Aston offers him multiple pairs of shoes, Davies only finds inadequate and prattles on about their unsuitability, producing a lot of genuine comedy in the process. Aston dreams of fixing up the building, but he never begins; eventually, we learn he spent time in a mental hospital where electroshock therapy damaged his brain, which is his excuse for paralysis. Mick has grand plans to fix up the building with the help of Davies, who seems more an invalid than a worker, but this too is all talk and no action.

What results is a series of scenes in which histories and allegiances are revealed, all through the unreliable storytelling of the play’s characters. These are sad tales of damaged people, but Pinter, like Chekhov, finds the humor in the despair. Davies’s objections to the accommodations would be reasonable if he was a simple curmudgeon, but as a hopeless vagrant, he is in no position to be so choosy. His sycophantic tactics with the two brothers, which change on a dime, are so calculated and yet ultimately futile that this is also very funny. Meanwhile, the brothers’ casual, loyal yet often incomprehensible relationship with one another is another source of comedy: the situation–taking in a chatty stranger no-questions-asked–is so absurd that it’s hysterical to see the brothers behave as though it were run-of-the-mill.

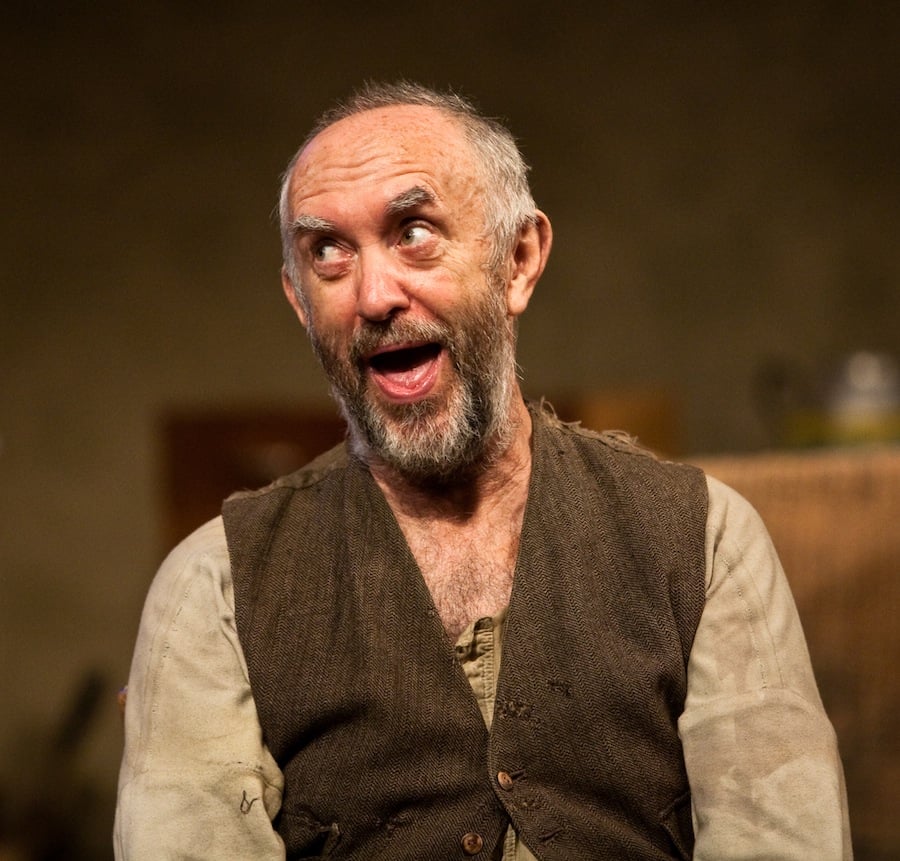

Jonathan Pryce is one of those actors who I would gladly pay to watch read the phone book for his effortless charisma. He’s a great character actor probably best known for his role as Keira Knightley’s father in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” series, but he’s got dramatic depth and comedic timing which may have been obscured in those films. As Davies, he gives a virtuous performance: he is charming yet pathetic, intense, nuanced and uses remarkable body language. Alan Cox and Alex Hassall may not have Pryce’s star power, but they are equally intense and refined, and their characters very carefully portrayed. They play their roles straight, letting the comedy come from the inherent absurdity rather than their own recognition of it.

There are a few unresolved and puzzling aspects to the production. Mick seems to enter and exit like a ghost, and more than once you may find yourself questioning what is actually real. At times, it seems like Mick and Aston merely offered Davies shelter as an opportunity to toy with him sadistically. This is confusing and detracts from a clear message, even if the message is merely that life is meaningless.

Like Chekhov, it’s easy to take Pinter too seriously because he deals in serious topics and themes. But “The Caretaker” is meant to be funny, and, directed delicately by Christopher Morahan, it does successfully elicit many laughs. That being said, this isn’t a mile-a-minute comedy; it carefully relishes in human foibles to subtly create humor. While this is a solid production, the scenes can feel clunky and frustrating precisely because of all the inaction. That’s the point. But you don’t have to like it. That’s just Pinter.