Universal language finds dedicated following on Stanford campus

”

Pardonu min…Ĉu vi parolas Esperanton?” is Esperanto for “Excuse me, do you speak Esperanto?” While most people will not understand this phrase, the language was created to be a universal tongue.

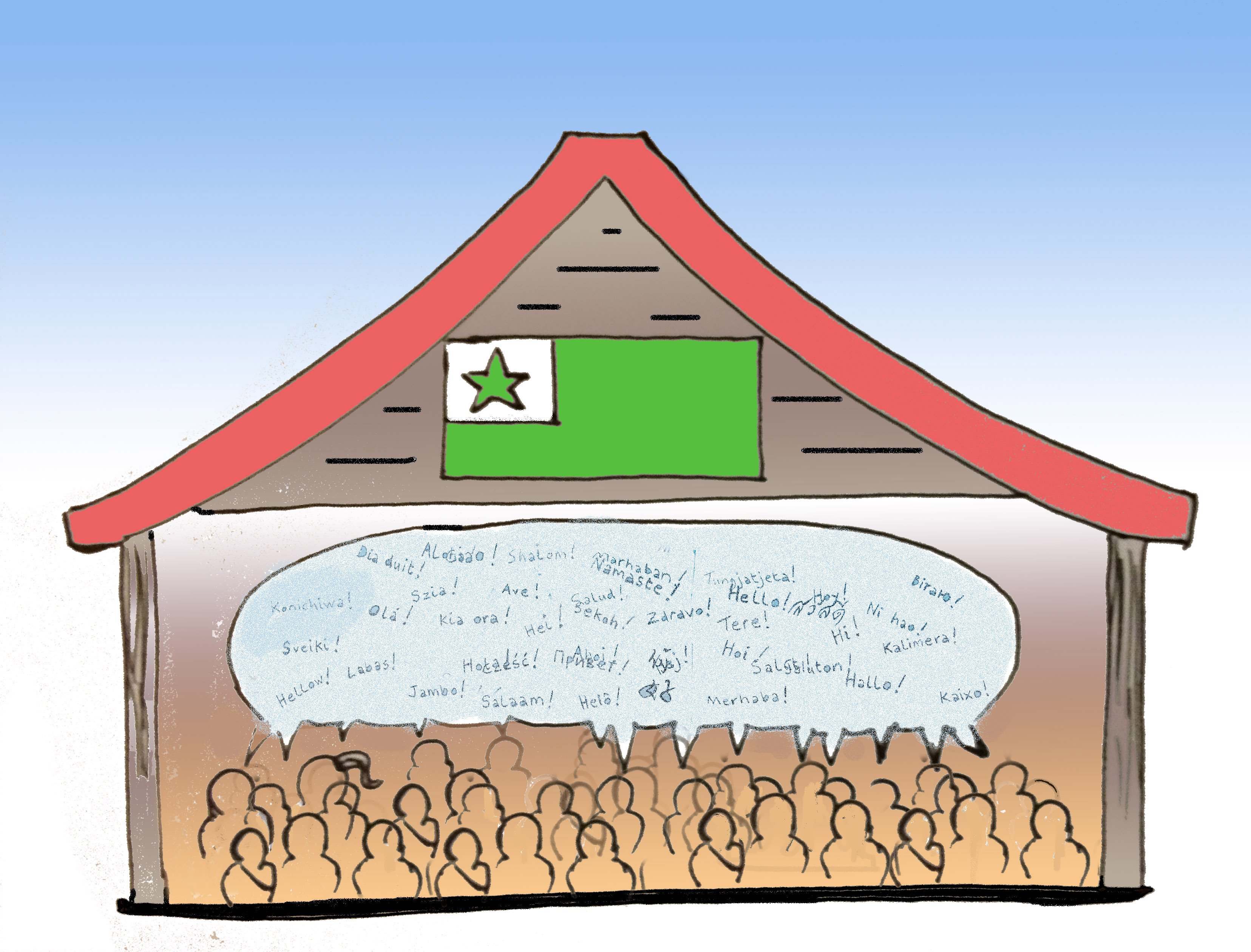

In 1887, L. L. Zamenhof designed Esperanto as the “universal language” in an attempt to break down the linguistic and cultural barriers that prevent cross-national conversations. In Zamenhof’s ideal world, everyone would continue speaking his or her native tongue, but speak Esperanto as a second “planned” language as a way to communicate with all people.

Stanford offers a free drop-in class called “Conversational Esperanto, the International Language” on Tuesdays from 6:30 p.m. to 8:30 p.m. at the Bechtel International Center . Students can take the class for two credits a quarter through the Linguistics Department . The class website guarantees that, following coursework requirements, students and community members will learn the language within a year.

“Even four lessons are enough to get more than just the basics,” the Esperanto at Stanford website reads.

The teacher of the class goes by the name Trio, explaining that Ed Williger, his given name, just doesn’t work in some languages.

“Trio is short and is pronounceable, and as of right now, I haven’t had any sort of problem with it,” he said.

He is reluctant to call himself a teacher, but since he has been teaching the class for 21 years, he “guesses that he is a teacher just because he’s been doing it for so long.” Trio teaches voluntarily and has been on the Stanford campus teaching Esperanto at the same location and time for the last 21 years.

Five students, ranging from young undergraduates to older alumni fill the small back room at the Bechtel International Center for his class, which begins with a cultural discussion as well as Esperanto music of all genres–from rap to rock.

One of the students in the class is Julie Spickler ’62, who started to learn Esperanto in the summer of 1994 in a 10 lesson course. By fall, Spickler had finished the class and her teacher urged her to come to monthly meetings of the local Esperanto community in San Francisco to converse with other Esperantists.

“I didn’t want to go at first because I thought it would be too difficult,” Spickler said. “But my teacher said to try it …you’ll find it is easier than you think…and sure enough I could understand half to three quarters of what the others were saying after just studying four or five months on my own without hearing anyone speak it.”

She brought a book to class, “Konciza Etimologia Vortaro,” a concise etymological Esperanto dictionary, explaining that Esperanto is rooted in multiple languages. Mostly, Esperanto borrows from Romance languages because of Zamenhoff’s own background.

“He was very idealistic and lived in a town in Poland under Russian rule where there were four or five language groups which were not always friendly to each other,” Spickler said. “He decided that to help decrease misunderstandings, they needed a common language. Though it’s true a common language doesn’t prevent conflict, it definitely helps.”

Spickler has been attending the Stanford Esperanto class for the past 10 years and says that the number of students in the class fluctuates widely. According to her, some students come in for only a few classes and then leave, thanking everyone for helping them learn Esperanto so quickly. What she finds curious is that new students come in periodically, but the new male students never seem to meet the new female students because they come in at different times, a trend that Trio also noted.

“We tell the guys, ‘Oh yeah, girls take this class. There are girls that speak Esperanto. You just never see them,’” Trio said. “This happens all the time–it’s a running joke among us old farts.”

Trio is a computer consultant who uses Esperanto almost every day. He said that he sometimes plays online Go, a board game that originated in ancient China, with other Esperantists around the world.

“Esperanto is my political work,” Trio said. “I believe in the ideals of it, and I believe that everyone can work together if everyone decides to keep Esperanto as a common language.”

“Esperanto really levels everyone out, since we all come in on the same ground, having it as our second language,” he said. “There are only a few native speakers of Esperanto, but they don’t dominate.”

Native Esperanto speakers are those born into families that speak Esperanto and acquire the language from childhood.

Trio became interested in Esperanto when he was studying economics in the 1970s. He had wanted to live in China, Sweden and Yugoslavia but realized that he would have to learn quite a few different and difficult languages. While reading the book “One Language for the World” by Mario Pei, Trio first encountered Esperanto and thought that it might solve the obstacle he was facing.

According to Trio, the Esperanto community around the world forms a unique and global bond.

“When the war in Yugoslavia broke out, I had stayed with Esperantists, who also took in other Esperantists who needed shelter,” Trio said. “You wouldn’t just do that with someone else if you both spoke English. Samideano–that’s what we call each other. It translates to ‘same idea person,’ but what it means is that we’re on the same planet on the same level.”

One of his other memorable experiences with the language was when he applied for citizenship in Hungary, and Esperantists translated the application for him.

Esperanto is the most widely spoken invented language in the world. While no definitive number of Esperanto speakers exists, the BBC reports between 500,000 and two million speakers worldwide. It has a national organization that sets linguistic standards and is the only invented language for which speakers can be certified. Many musical lyrics and works of literature from different languages have been translated into Esperanto for the Esperanto-speaking international community to enjoy. For example, Trio finds the Winnie the Pooh Esperanto translation “fantastic.”

At Stanford, Scott Parks ’13 co-founded the Esperanto Club. Parks became interested in learning Esperanto during the summer between his high school senior year and his freshman year, finding it “really, really easy.”

“We decided we wanted to make a student group with the local Esperanto community and we have been meeting since then,” Parks said.

Although many of the club members were interested in Esperanto, many were also interested in what Parks called “conlanging,” or constructive languages.

“So we changed our focus to conlanging and linguistics in general and are working on learning Mandarin specifically this quarter,” he said.

Parks noted that the local Esperanto community is strong but aging. According to him, not enough members in the student community or the younger generation are engaged in the effort to learn and spread the language.

“Esperanto isn’t doing as well as it was 20 years ago,” he said. “But it isn’t going to die out anytime soon either–it still has an international standing. Esperanto gatherings…are still going strong.”