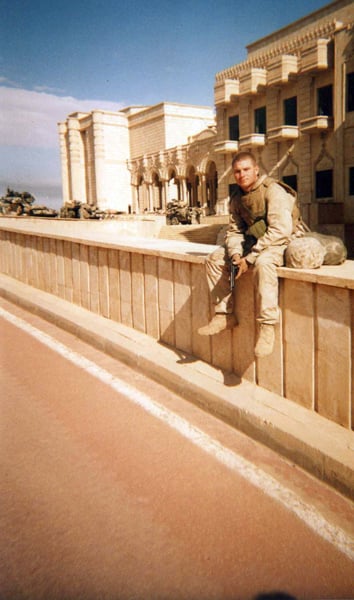

“If my country was going to war, there was no damn way it would happen without me,” said Dustin Barfield ’12, a two-time combat veteran who transferred to Stanford in 2009.

While most students at Stanford enter their sophomore year reminiscing on their adventures as college freshman, Barfield had a profoundly different experience in the back of his mind. Despite attempts by his family and friends to dissuade him, he enlisted in December 2001 and served for four years in Iraq.

“They yelled at me,” Barfield said. “They threatened me. They told me to change my mind… they even tried to bribe me. I was already set though. It was happening.”

After serving in Kuwait, Barfield was deployed again to Iraq in August 2004 for the second battle of Fallujah, one of the bloodiest conflicts in the war. But according to Barfield, the American media wrongly sensationalized the military, causing him to lose confidence in public perception.

“You get back home, and you hear about 13 sergeants killed and one severely wounded,” Barfield said. “You don’t hear about us handing out humanitarian rations and building schools. You don’t hear about torture victims coming up to us, bawling, crying and hugging us, saying ‘George Bush…very good!’”

“It’s 99.9 percent waiting around, pointing your weapon at the middle of a desert, waiting on super high alert for someone who is going to try to kill you at any moment. Waiting and waiting and waiting.”

Upon his return from the Marine Corps in 2006, however, Barfield encountered the civilian-military divide. It’s a divide several members of the military at Stanford feel and acknowledge.

“There’s been a historic divide between civil society and the military–and this is something that has happened since the Vietnam era,” said Haney Hong ’03, president of the Stanford Military Service Network (SMSN). “Generationally, because people have had less exposure to the military, they have less of an understanding of it.”

According to Hong, who served as a submarine officer in the Navy after completing the Navy Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) program at UC Berkeley, SMSN was founded to bridge the civilian-military divide as well as to help the community understand that Stanford military veterans are “just like everybody else.”

“It’s a lot of misconception, and that’s not necessarily [the community’s] fault,” Hong said. “When you’re not exposed to it very much, you don’t really understand. The image of someone in the military doesn’t mesh with what somebody thinks about as a Stanford student.”

William Treseder ’11, a Marine veteran and friend of Barfield, describes how not looking like the “typical military guy” helped him break the ice more easily.

“If you know he’s a veteran but doesn’t look like a veteran, that creates an interesting tension in your mind and you wonder why is this guy not conforming to the model in my head?” Treseder said.

Similar to Hong, Treseder suggests that part of what contributes to this negative attitude dates back to the Vietnam War era. As a result, he feels Stanford is also unprepared to support veterans returning back from war.

“Probably the single biggest part of this is the big chunk of people from the late ‘60s to mid-‘70s whose impression of where Stanford is now is very different from actually where it is,” Treseder said. “They think it’s the place that burned down the Navy ROTC building and that hates the military.”

Opinions vary in terms of what Stanford can do to improve the experience of war veterans on campus. Lillian McBee ’14, a ROTC student and active member of SMSN, believes that dialogue is the most organic way in promoting awareness between the civilian and military community.

“I think those types of questions, where we just get to know one another person-to-person is, at the end of the day, the best way of bridging this divide,” McBee said. “In general, even in my freshmen year, the reason I was afraid for coming out in my dorm was that there were a lot of the protestors for anti-ROTC groups. But now I see that if I talk to them over the years, get to know them a little bit better, they’ll still respect me for the fact that I am pursuing something that I love.”

While Barfield is grateful for the Marine Corps’ post-war support including services for his struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), he believes that Stanford still has room for improvement.

“Stanford University could do a better job connecting with its veterans, understanding their issues and being more sympathetic to them,” Barfield said. “It’s not the same case mentally or emotionally as an 18-year-old who was valedictorian.”

Toward that goal, SMSN is expanding and partnering with the Haas Center for Public Service and the Graduate School of Business.