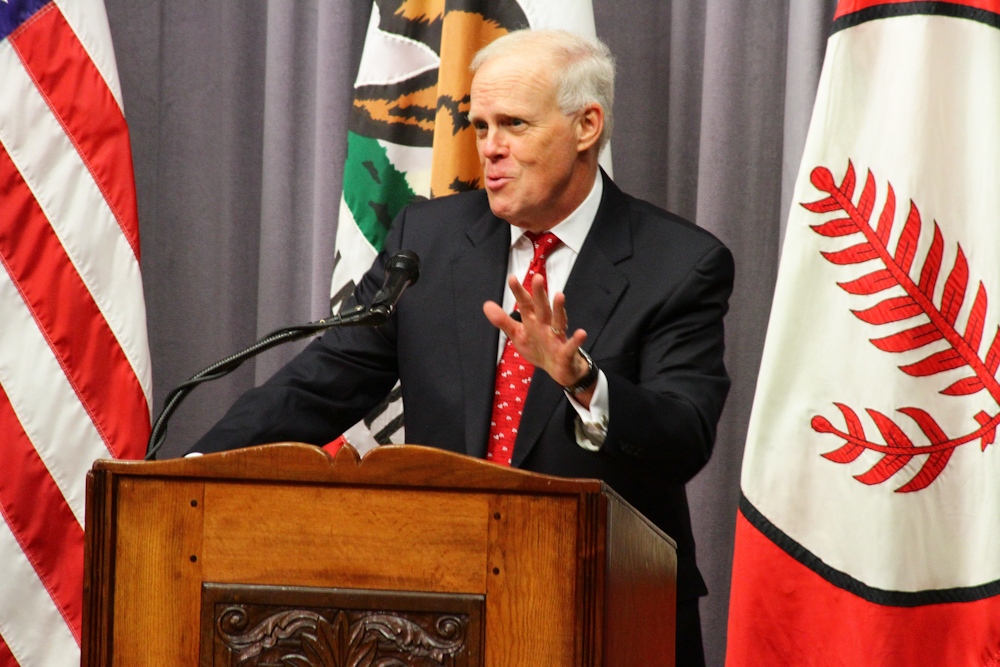

Stanford University President John Hennessy sat down with The Stanford Daily on Oct. 29 to discuss a wide range of topics, including online education, Stanford’s failed campaign for a New York City campus last fall, Stanford’s fundraising successes and more. This is the first of four installments of that interview; this one focuses on online education.

President Hennessy was on sabbatical for the second half of winter quarter and all of spring quarter 2012. During that time he still participated in a number of Stanford events, visiting Beijing to dedicate the Stanford Center at Peking University, stopping by campus for the launch of the Campaign for Stanford Medicine and visiting the Bing Overseas Program in Florence.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): How was your sabbatical?

John Hennessy (JH): It was good. It was a nice opportunity to get some reading done and do some thinking about long-term things and the kind of thing that you don’t have the opportunity to do when you have a schedule just jam packed with…events.

TSD: How did that prepare you for this year and future years?

JH: Well, I had a very large stack of books on higher education, everything from trends to changes to what’s happening with student population and how they’re thinking about college. [The sabbatical] gave me a chance to read them. Some of them have been sitting there for a few years, so it was a good opportunity to do that. Then…thinking about long-term directions for the University, what are the key things to understand and begin to contemplate, what do we want to do about online education? And what role does it have at Stanford? How do we think about doing what’s right for us as a University in the online space as opposed to what everyone else thinks we should do?

The Faculty Senate has heard two reports in the past six months on online education. In August, John Mitchell was appointed the inaugural vice provost for online education; this is just the third vice provost office created in the past 20 years.

TSD: What do you think the biggest challenge for us in terms of the online space is?

JH: Well, I think there’s more than one. I mean the first challenge is probably to say, “How do we use that technology to make the learning experience for our on-campus students better?” And right now, we’re trying a bunch of different things: flipped classroom and things like that, but we haven’t yet gotten to the stage where we say, “Okay, now we think we have an idea well worked out. Now let’s go try to scientifically understand whether or not students are learning more in that environment, whether they’re better engaged, how they feel about the experience.” So we’re going to have to do this whole process of actually saying, “Is online better? Is it worse? Is it the same?”

Let’s not just do it anecdotally but build up the capability to do an assessment so we can say, “We’ve got data. These students in the online class are learning as well [compared to current methods].” So that’s going to be a key for all of this…It’s early on. It’s the Wild West out there. So that’s okay, but there’s way too much anecdotal, situational [evidence].

Then I think, figuring out what role Stanford wants to have. The MOOCs [massive open online classes] are more about self-made, motivated learners than they are about having another 10,000 students at Stanford. They’re more about sharing some of what the University does with the rest of the world, particularly those who don’t have access to education.

The data is quite compelling in this. If you look at sub-Saharan Africa, the place where education is hardest to achieve – in the Western world, 70 percent of the students of college age are enrolled in either a two-year or a four-year program and the average years of education you can expect if you were born today in the United States is 16 years. If you were born in sub-Saharan Africa, then less than 10 percent of the kids go to any kind of college [or] any kind of post-high school, and your average years of education are eight. So there’s something I think to add to the rest of the world…And that’s a good thing for Stanford to do, it’s a good thing to do for the rest of the world, and then we can do it with relatively little cost associated with us at the end.

So we have our on-campus students and we have this broad outreach sort of thing, in the middle I think we think about how can we use online to enhance what we do today perhaps in professional and continuing education, perhaps with respect to master’s degrees.

I don’t see fundamentally changing the undergraduate, four-year, residential experience because that is, in some sense, the gold standard. It’s the thing we do know how to do really well. Now, will other institutions in the United States try to develop an online alternative to that? Yes, they will, because the gold standard is, by its nature, expensive. So it is, in my mind, the ideal educational opportunity for the really best students for the institutions that can afford to provide that together with families. But it can’t be the entire solution given the cost of education in the U.S. So people are going to have to figure out how to use online in that other space and should we contribute content to it? What role could content coming from Stanford play in that? We don’t know the answers to that, but there probably are opportunities there that would be good things.

Numerous Stanford students, professors and affiliates have founded online education startups, such as Coursera, Udacity, Class2Go and Venture Labs. All but Udacity have formal partnerships with the University.

TSD: There are a lot of affiliated, Stanford-related groups in the online education space. How do you feel about that? Is that encouraged? Do you encourage faculty to experiment with this stuff and do their own thing or is it just sort of something you don’t actively discourage?

JH: Well we don’t discourage it and I think in some cases we felt, to move the technology along, it would be nice to have something out there that had a similar kind of business model and similar approach to what we were thinking so we could develop a good working relationship with them. So I think it’s a combination: We believe that getting some external entities out there will probably accelerate the rate at which this technology moves, which I think it has. And that’s generally a good thing.

Tomorrow’s installment will focus on Stanford’s failed bid for a New York City campus and Thursday’s will center on long-term projects for the University.