Human biology and political science: two subjects that, on the surface, appear to be quite different. Eric Mattson ’15, however, finds his passion in the reconciliation of these two worlds.

“I am interested in anatomy, physiology and the life sciences,” Mattson said. “But I’m also equally interested in access to health care and public health issues in general.”

Cesar Torres ’13 also ascribes to the philosophy of “one [major] informing the other.” As a double major in computer science and art, he says taking classes in both of his interest areas has helped to enrich his designing skills.

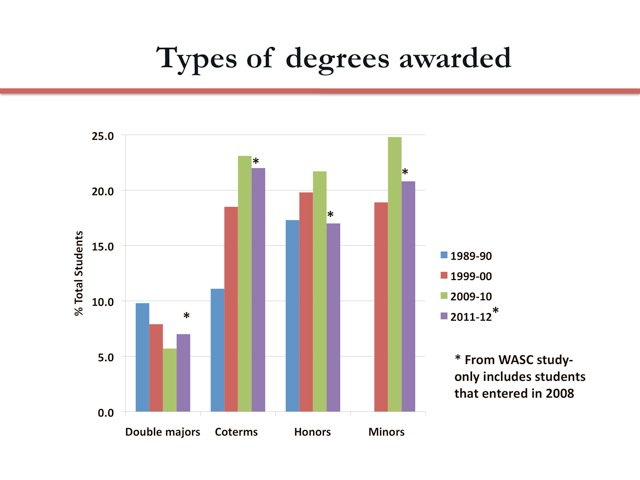

Both students are in a shrinking minority of double majors, according to an October Faculty Senate report. While nearly 10 percent of Stanford undergraduates graduated with a double major in 1990, that number has dropped by half two decades later, hovering just above 5 percent in 2010.

This data might be skewed, according to the report’s author, biology professor Martha Cyert, because undergraduates in the 1989-90 data set were not allowed to minor. During the same 20-year period, the number of students choosing to minor has grown to encompass nearly 25 percent of the undergraduate population.

Despite this fact, department chairs say they have continued to feel the effects of fewer students double majoring in more recent years. Increasing numbers of units required for majors in areas like economics, English, earth systems and international relations likely contribute to this trend.

“Undoubtedly, the number of our double majors has declined in the last few years,” said Gavin Jones, chair of the English Department, during the Oct. 11 Faculty Senate meeting. “We used to have a lot of English/HumBio double majors and double majors in other subjects, and that’s gone down quite a bit.”

Josiah Ober, chair of the Political Science Department, has also seen a drop in students graduating with a double major in his department.

Still, nearly 20 percent of students in the Political Science Department have a double major, and 10 percent have at least one minor, according to Ober. He said these statistics are due to the department’s number of major requirements, which recognizes that students may have other academic interests outside of the department.

“I think that the logic is that we keep that number as low as possible within the framework of the units required to have the necessary command of the subject,” Ober said.

Approximately 20 percent of students in the History Department graduate with a double major as well. According to Karen Wigen, chair of the department, the history major requirement of 65 units is “not a heavy load.”

“We value intellectual exploration,” Wigen said. “That’s one reason why we’ve kept it relatively light. You don’t have to study history from the very first day in order to be able to major in it — we don’t want that to be the case. You can stumble into a history class in sophomore year and still be able to major in it. We want people to be able to find us.”

And indeed, most undergraduates do change their minds once or more while choosing a major. Mattson came to Stanford as a bioengineering major with a premed focus. For him, the turning point was his Alternative Spring Break experience.

“I went to [Washington] D.C. on the project to mobilize voters during election year,” Mattson said. “The experience really solidified my passion for political science.”

Finding room for intellectual exploration, however, becomes difficult for students double majoring. Students who double major often have to plan earlier how they are going to meet all their requirements in time to graduate in four years.

“The most challenging part has been keeping track of all of the unique requirements for each major and making sure that I planned ahead to complete all of the respective requirements in time,” Torres said.

While Wigen said it is “impressive” that a student should have the enthusiasm and passion to delve deeply into two academic disciplines, she also cited advantages to exploring a variety of courses.

“There’s a very high payoff to taking one course in a field,” Wigen said. “As long as it’s deliberate and thoughtful, I think it’s a really good use of time to explore disciplines in a specific way, especially as the disciplines are working very hard to create gateway courses for non-majors.”

Wigen also points to advanced language work, study abroad and research projects that all enhance an undergraduate career.

“You should think carefully before double majoring at the expense of all that other stuff,” she said.

Kirsti Copelend, director of residentially based advising, agrees. For her, Stanford is “a candy shop of opportunities,” and double majoring is not the only way of living two passions.

“Choose your major, and imagine for yourself how you’re going to tell the narrative of your transcript, and the other courses you took outside of that major — it can be just as powerful when you’re talking to an employer or graduate school,” Copeland said.

This philosophy is precisely the one that guides Mattson’s journey as a Stanford undergraduate. He is heavily involved in on-campus extracurricular activities and wants to study abroad during a quarter. He acknowledges that he might rethink his choice of double majoring if that began to affect other things he cared about.

“I’ll be comfortable with the fact that if that doesn’t ultimately come through, I’ll still be able to say that I have a true passion for the subject — I might just not have a major in the subject,” Mattson said. “At the end of the day, taking advantage of all the opportunities here at Stanford is going to be more important than just being able to say that I have more than one major.”