When it was founded in 1891, Stanford was ahead of its time: The school did not charge tuition fees, it admitted women and it had no religious affiliation. There were Asian American and Native American students in the first classes. But despite these measures, Stanford was, for the first 70 years of its history, overwhelmingly male – and even more overwhelmingly white.

As late as 1960, there were only two black students in the entire freshman class. In 1965, just one Native American student was enrolled in the University. Women were not allowed to make up more than 40 percent of the student body – although the actual percentage was much lower.

The number of Latino and Asian American students was also low. In fact, during much of the early part of the 1900s, the small number of Asian American students at Stanford lived in the Japanese or Chinese clubhouses. The clubhouses were separate dormitories built with private funds in 1917 and 1919, respectively, in response to racism the students encountered in the University dorms. The Japanese Clubhouse stood until 1968, and the Chinese Clubhouse, which was located where the Law School now stands, until 1971.

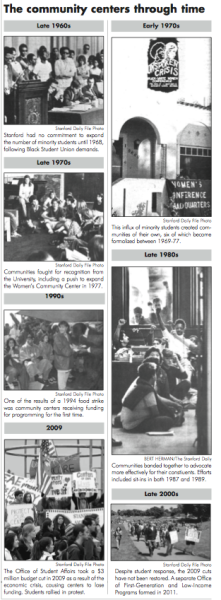

These clubhouses served as the earliest iteration of what would eventually become Stanford’s current system of six community centers, which were formed in the late 1960s and late 1970s as a response to the growing needs of a more diverse student population. This year, for the first time in their 40-year-plus history, the centers are being reviewed by Student Affairs under a routine assessment on all of offices under its purview starting in 2009 (see “Community centers undergo first review in history“).

“Creating a sense of belonging”

The small number of minority students enrolled at Stanford began to rise in the 1960s. As the civil rights movement gained national prominence and attention, Stanford began to recruit minority students, as a result of both student pressure and because of national changes.

By 1967, there were more than 100 black students enrolled at Stanford, and in 1970, the freshman class included 25 Native American students. Both increases came as results of a University recruitment push targeted at increasing minority enrollment. Though smaller than they are today – this academic year, there are 637 black or African American students and 250 Native American students out of an undergraduate population of 6,927 – these numbers marked the beginnings of a new commitment to diversity by the University.

According to Frances Morales, director of El Centro Chicano, the late 1960s saw “the beginnings of Mexican Americans, Latinos, attending universities for the first time.”

“There has long been a presence of Native Americans [at Stanford],” said Karen Biestman, director of the Native American Cultural Center. “But it really didn’t escalate to a programmatic commitment until the late ’60s, early ’70s.”

Once on campus, the minority students quickly formed communities of their own. In five years, students founded the six major community organizations: the Black Student Union (BSU) in 1967, the Asian American Students’ Association (AASA) and the Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlan (MEChA) in 1969, the Stanford American Indian Organization (SAIO) in 1970, the Gay People’s Union in 1971 and the Women’s Collective in 1972.

“At that time, there were not so many students of color at Stanford,” said Cindy Ng, director of the Asian American Activities Center, “So it was part of students creating a sense of belonging for themselves on campus.”

This early activity took place amid the anger and unrest following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968. The murder produced different reactions in the Stanford community. According to a Daily article printed the following day, some members of one freshman dorm cheered King’s death and held a food fight afterwards (“University answers black demands,” April 9, 1968). The Black Student Union (BSU) held a rally in White Plaza in which 40 students burned an American flag.

Four days after King’s death, at a University-wide colloquium on white racism at Memorial Auditorium, 70 BSU members walked onto the stage and took the microphone from former Provost Richard Lyman. The BSU chair, Keni Washington ’68, told the capacity crowd to “put your money where your mouth is,” and issued 10 demands to the University relating to its responsibilities towards black and other minority students.

Two days later, the University had agreed to nine of the ten.

These commitments helped lead to the founding of the Black Student Volunteer Center – now known as the Black Community Services Center (BCSC) – in 1969, making it Stanford’s first community center. Others followed: the Asian American Activities Center (A3C), the Gay People’s Union and the Women’s Collective were founded in 1972, the Native American Cultural Center (NACC) in 1974 and El Centro Chicano in 1977.

“Out of those moments of the ’60s, both on and off campus, the University rose to the fact that it was committed to these values [of diversity],” Ng said. “It’s in keeping with the founding mission, but I think it’s a part of the social movements that occurred.”

Karen Biestman, NACC director, credited an at-times acrimonious partnership between students and the University for the growth the community centers.

“I do think [the establishment of the NACC] was student-led, but there was a partnership” between students and the University, Biestman said. “And that partnership can be credited to the evolution that these 25 [recruited Native students] built upon themselves.”

“I think students had organized and asked for additional resources,” said Benjamin Davidson, the director of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Resource Center (LGBT CRC). “Stanford rose to the challenge.”

Rallying for University funding

But getting the University to rise to the challenge was not always easy. In their early years, the centers were smaller and ran on shoestring budgets. They were staffed entirely by students, and received no money from the University for events or other programming.

“We all recall having to…sell food or something…to raise money,” Morales said.

“These six centers didn’t happen all at once. It was the result of many years,” said Vice Provost for Student Affairs Greg Boardman. The additional funding the centers have received through the years “was based a lot on student advocacy, and trying to meet the needs of students.”

Through the 1970s and 1980s, student efforts to gain greater recognition and financial support from the University on behalf of the centers were mixed with a number of other demands – political, curricular, economic and social.

Often led by coalitions of the main community groups, students held rallies and sit-ins fighting for the removal of the Stanford Indian mascot, more funding and space for community centers, the establishment of ethnic-themed dorms, the removal of the “Western Civilization” requirement, greater efforts at minority recruitment, divestment from apartheid-era South Africa, the creation of a vice provost position for minority affairs, the creation of ethnic studies programs, an increase in the financial aid budget and the hiring of more minority faculty members.

One of the most famous sit-ins came in 1989, when students from different communities came together with a variety of grievances. Sixty of them formed the Agenda for Action Coalition, and, on May 15, they occupied then-President Donald Kennedy’s office until the University responded to their demands. In the next day’s issue of The Daily, Kennedy called it the “gravest” student protest in 16 years (“Students seize Kennedy’s office, 55 arrested,” May 16, 1989).

Though the administration’s original response was harsh – Santa Clara County police arrested 55 students later that day – the sit-in produced results. Many of the activists’ demands, primarily related to the administration of community centers and the hiring of minority faculty, were met.

It was during the 1980s that Stanford hired professional staff for the community centers – first on a part-time basis, then, towards the end of the decade and the beginning of the next, on a full-time basis. According to Ng, it was not until 1994 that community centers began to receive funding for programming, a result of a hunger strike that year by Chicana students.

“A beacon to the people they serve”

From 1994 on, the community centers settled, more or less, into their current forms. In 2001, the University again increased funding to the centers; these increased budgets lasted until 2009, when in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the entire Office of Student Affairs took a $3 million budget cut, which resulted in a budget cut for all the community centers. The funds cut in 2009 have, for the most part, not yet been restored.

For almost the last 20 years, though, the addition of programming funds has led to an expansion of services provided by the community centers. Though each community center tailors its services to its constituent population, the outlines of each are broadly similar.

Each center offers academic support, psychological support and a physical space where students can learn more about their identities.

“If it wasn’t for a place like the Black House…I would have struggled a lot more,” said Shawn Dye ’14, a staff member at the BCSC. “Community centers are a beacon to the people they serve, and they’re also very welcoming places for people to come and learn.”

Because of the community centers’ unique place in campus debates over diversity during the last 40 years, the centers at Stanford have developed in a way that few centers at other universities have. Even compared to its peer institutions, Stanford’s community centers are unusually large and well supported.

“Not all universities even have offices to deal with issues of diversity,” Ng said. Of those that do, “There’s our model, there’s the multicultural model, and then there might just be staff people.”

In the multicultural model, used at UC-Berkeley and at Princeton, among others, all minority communities are housed in one large “multicultural center.”

“For some, they argue that the multicultural model is better because if you put the students together, they can learn from each other,” Ng said. “But I think to really develop a depth of understanding and to be able to learn from people who are different, which is critical, there needs to be a strong sense of who you are to begin with.”

Another criticism Stanford’s model faces is that, by separating each community center from the others, the school forces students to choose one identity over another.

But the center directors dismissed that concern.

Having a separate space for each community, Biestman said, allows students to gain a deeper understanding of their identities and a closer engagement with the issues their communities face than would otherwise be possible. And most importantly, she added, each center stands as a symbol of the University’s commitment to diversity.

“It’s really more than just a place. It is the embodiment of this history, the embodiment of this relationship, of the partnership and the promise of the future,” Biestman said of the NACC. “[It’s] an institutional commitment we can build upon so we use this actively not only to support current students, but, when future students come, when recruitment events come by, we say that Stanford has a physical legacy that others don’t have.”

The number of African American or black and Native American students listed in this article as currently attending Stanford has been updated to reflect the total undergraduate population in 2012-13.