The idea of taking out loans was considered taboo in Monica Alcazar’s family.

“I grew up in a Mexican household and it was always like ‘Don’t get yourself in debt,’” Alcazar ’13 said.

But when Alcazar’s parents decided they weren’t going to support her Stanford education after she came out to them about her sexuality, Alcazar – now a financially independent student – had to turn to loans. She started taking out federal loans, including Federal Perkins Loans, during her junior year. She will graduate with about $11,000 in debt and has to forfeit the option of graduate school to be able to pay it off.

“I thought I had a narrowly defined, direct trajectory of what my education process was going to look like and now it’s been interrupted because I’ve taken out loans,” she said.

Alisa Royer ’11 works as a conservation biologist at the Stanford Department of Land, Buildings and Real Estate paying off a $30,000 principal debt from three private loans.

Because her parents’ expected contribution did not qualify for need-based financial aid, and her younger brother started college soon after she did, taking out loans also did not feel like a choice.

“Paying it outright would have caused serious problems for my parents so I felt like loans was not a choice,” Royer, who is a Daily photo editor, said. “It was pretty much a requirement; if not in writing, in practice it felt like a requirement.”

Though Alcazar and Royer’s situations match national stories on increasing numbers of students graduating with larger debt, they are a minority on Stanford campus for having taken out loans in the first place.

The debt landscape

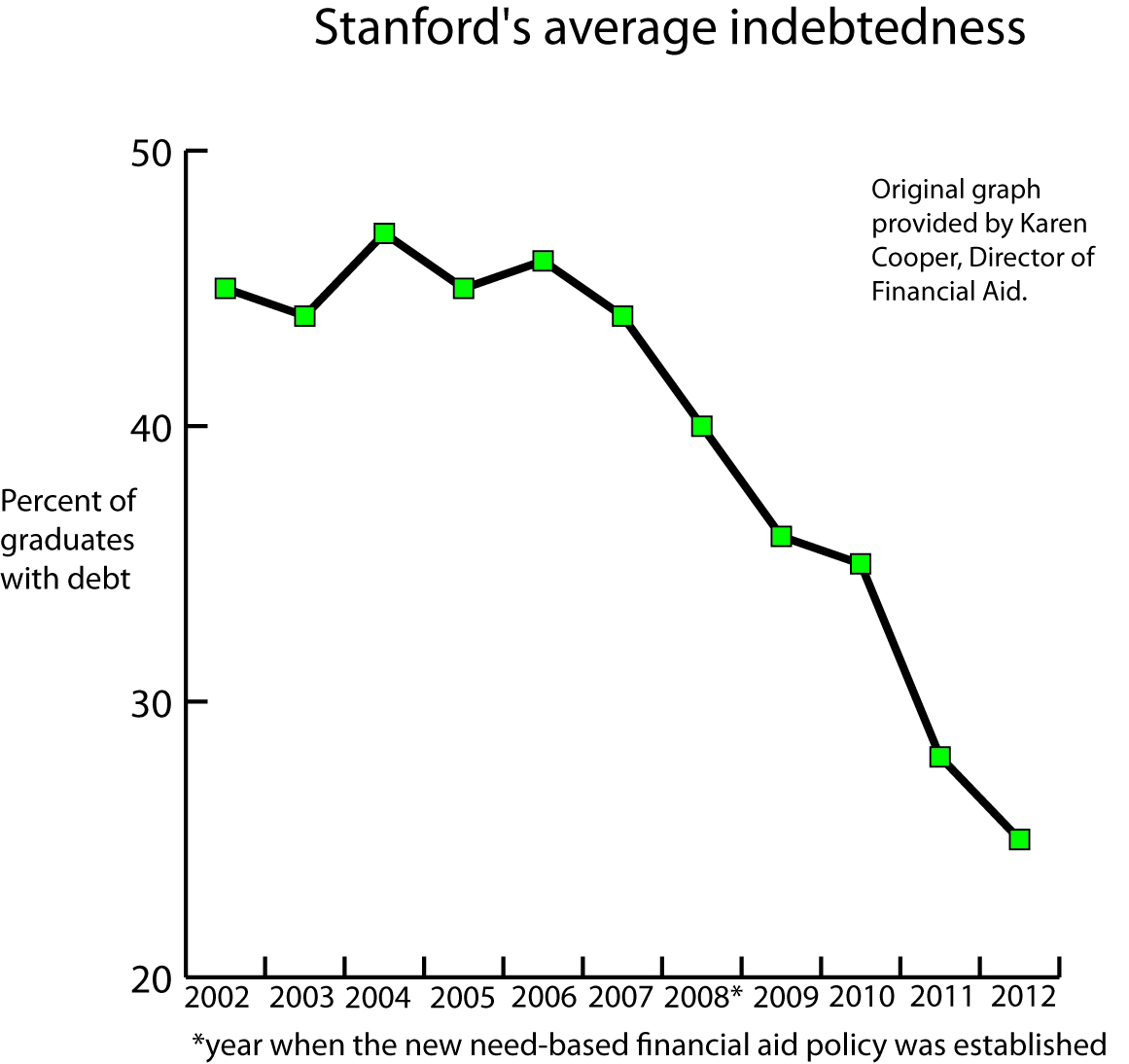

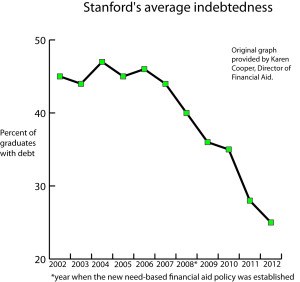

Compared to national statistics showing the number of college students graduating with loans increasing within the last few years, Stanford defies the trend with only 25 percent of the class of 2012 graduating with debt.

Beginning around 2009, the proportion of Stanford graduates with debt from federal and private loans dropped from the average 44.4 percent of years prior to 36 percent and then well down to 25 percent last year.

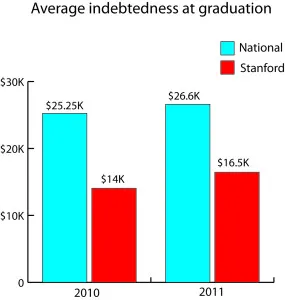

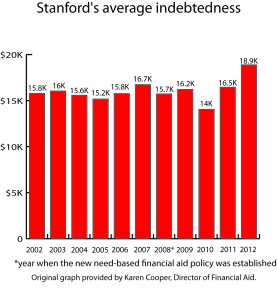

Conversely, the average indebtedness of Stanford graduates has seen increases from $15,724 in 2008 to $18,883 in 2012. However, the average remains below the 2011 national average debt of $26,600 according to The Institute for College Access and Success (TICAS).

Karen Cooper, director of financial aid, said that the new need-based financial aid program – implemented in the 2008-09 school year – is in large part responsible for the decreasing percentage of Stanford students taking out loans.

The new program does not expect students to take out loans as part of their financial aid package. It also reduces the expected parent contribution to zero for families making less than $60,000 a year and eliminates tuition payments for parents earning less than $100,000 a year.

Cooper explained that the average dollar amount of debt has increased because the pool of borrowers has decreased and the few that remain borrow more. She added that many of the students borrowing are from socio-economic backgrounds where families do not qualify for need-based financial aid.

“The main reason students here at Stanford borrow is to help parents with the expected parent contribution,” Cooper said.

However, not all the 25 percent of borrowers come from more affluent socioeconomic backgrounds.

While high-earning families tend to take out more private loans than federal loans, there are several reasons students who qualify for large institutional grants still opt for federal loans.

Multi-faceted reasons

According to Cooper, under the new financial aid program many students are eligible for low-cost federal loans with yearly maximums, meaning there is a limit to how much they can borrow.

Diana Gonzalez ’13 has used the Federal Perkins Loan every year since freshman year and will graduate with about $7,000 of debt.

Even though Gonzalez’s parent contribution is zero, she still relies on the loans to pay for extra expenses not covered by financial aid, like books and dorm supplies.

“After all my financial aid is taken care of, the refund that I get is very little and it’s not enough for me to survive for the quarter so the loan helps with that,” Gonzalez said.

Cooper said that students with a financial aid package like Gonzalez’s would typically use loans to cover their expected student contribution that they may choose to fulfill through federal work-study or outside scholarships.

Though the current financial aid policy makes loans more of a personal option varying between individual families, for some students whose parents still qualify for need-based aid, loans may be required as with Alcazar.

The process of reapplying for financial aid as an independent student was frustrating, Alcazar said, but with the help of an LGBT liaison in the financial aid office she was able to sift through the paperwork and figure out what loans she would need to take on to finish her degree.

“The worst thing you could do was take out loans for higher education but it’s because I’ve been able to take out these loans that I can even have a higher education,” Alcazar said.

While Gonzalez and Alcazar are anxious about having to graduate with debt and how they will pay off the debt, they have some safeguards to rely on because they opted for federal, not private loans.

Federal versus private

When students choose to take out loans at Stanford, the financial aid office first recommends federal loans and insists on federal loans even when providing information on private alternatives.

Cooper points out that federal direct loans have high interest rates when compared to private education loans and they have annual maximums. However, private loans can have variable rates that may increase over time and do not have any repayment safeguards in place like federal options.

The Federal Perkins Loan is unsubsidized — meaning it does not incur interest while a student works on her degree and students can wait until after graduation to pay it off.

Additionally, when tuition rises, students taking out private loans may accumulate more debt whereas those eligible and taking out federal loans can find solace in institutional grant funding that matches tuition increases.

Tuition rose 3 percent for the 2012-13 school year but institutional grant funding in the financial aid budget rose with it.

The previous financial aid policy — which applied to Royer when she was admitted — expected students to take on loans as part of their aid package. The new process that took place is not retroactive, so the University could not help Royer with her previously incurred loans.

Royer’s family falls into the category of students that Cooper said are more likely to go for private loans than federal.

“Students who are using the private loans, I can say very comfortably, those are not our students who are coming from low income backgrounds,” Cooper said.

“Those are students who are coming from more affluent backgrounds and it’s family choices that a driving whether or not they are taking those private loans,” she added.

When looking back at the process Royer felt that even though she was expected to take on loans from the beginning, she did not get the kind of guidance Alcazar found at the financial aid office but the Student Services Center (SSE) helped her deal with any student bill complications.

“Everyone pretty much tells you [Student Services Center] is where you need to go,” Royer said.

Helen Grieco, the Northern California organizer for California Common Cause — a nonpartisan, bipartisan citizen’s lobby group that offers college students activist training for democratic reform, including the topic of higher education — said that students with private loans face a greater risk.

“Private companies are in it to make money where you’re seen as the consumer,” Grieco said.

Based on her experience working with students in debt, Grieco said that students need to be calculating and cautious in taking on any type of loan, especially when thinking about the financial consequences they will face.

Stanford silver lining

As the percentage of students facing debt at Stanford decreases, the national statistics continue to trend toward more students facing larger debt amounts.

Grieco said that 75 percent of the Stanford class graduating debt-free is “not the norm.” According to TICAS statistics, 51 percent of California college students at both public and private institutions graduate with debt.

Though education costs are rising, there is still evidence that getting a college education is economically advantageous.

A report published by the Georgetown University Public Policy Institute on Aug. 15 revealed that the unemployment rate for recent four-year college graduates is 6.8 percent compared to the 24 percent unemployment rate for high school graduates.

On the matter of getting a job to pay off debt, Grieco said Stanford graduates have a “silver lining.”

This year, when Stanford faced a 5 percent decrease in Cal Grant funding, the financial office was able to offset that with more institutional grant funding totaling $130 million. There is also the benefit of a Stanford degree that Grieco said will help graduates find a job faster, and ideally pay off debt quicker.

Gonzalez considers Stanford’s financial aid program a blessing and recognizes Grieco’s emphasis on the Stanford degree, including for those on private loans.

“Even though they have a lot of debt, the ball’s in their court where they’re going to be able to find a better job or more quickly than someone who graduated from a state school,” Gonzalez said.