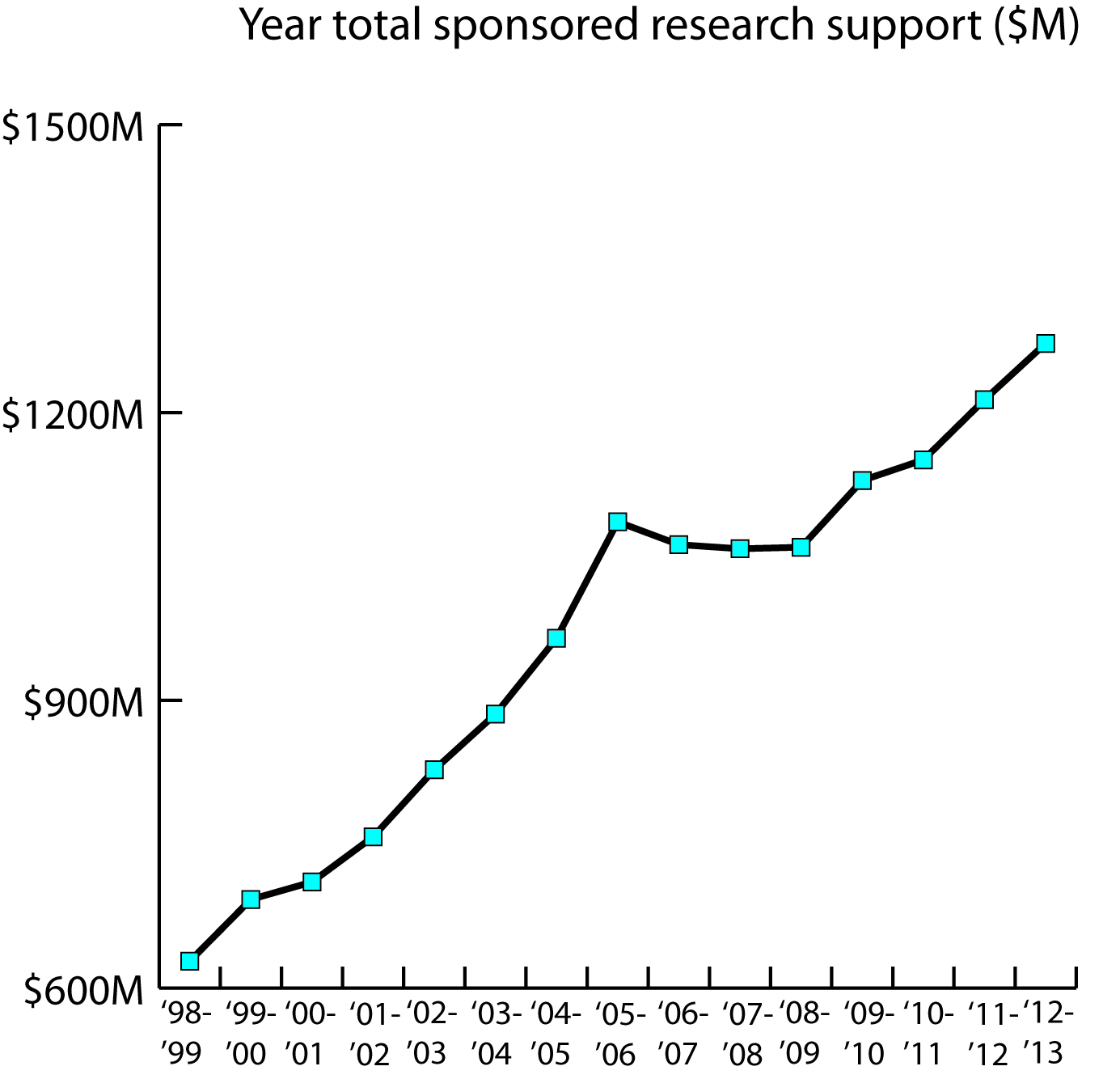

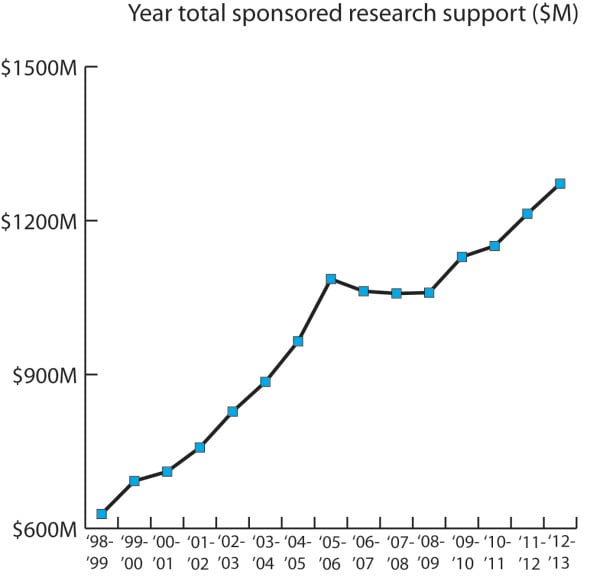

Even as Stanford continues to bounce backstrongly from the impact of the 2008 recession, renewed uncertainty about potential cuts in federal spending may prompt a more serious challenge to the University’s ability to fund faculty and students in the years ahead.

Federal funding currently accounts for 84 percent of all sponsored research at Stanford, which itself constitutes 28 percent of the University’s consolidated revenues. This funding comes from sources as diverse as the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Department of Energy (DOE).

Almost all research at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is federally funded by the DOE according to Andy Freeberg, media relations manager at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

Despite the significance of research funding for the University as a whole, individual faculty members make grant applications independently without administrative supervision.

“Keep in mind the University does not do research – faculty does research,” said Dean of Research Ann Arvin. “The job of the University is to help them get those grants submitted and provide the resources they need to do the work [such as labs and libraries]. We are definitely not in the business of reviewing faculty proposals.”

Arvin noted that recent federal fiscal retrenchment has already become evident in increased competition among grant applicants who are seeking a diminished pool of research funds. Stanford’s success rate in obtaining federal grants – which are peer-reviewed at federal agencies – is historically about 30 percent.

“Our faculty still continue to do well but as you can imagine it depends on how many applications you submit,” Arvin said. “If you want to have an active research lab you have to have two to three research projects to keep the show on the road. When funding is tight, the faculty has to submit more grants. It’s not easy these days.”

Graduate student funding

Sustained uncertainty about potential cuts in federal spending could have lasting and explicit ramifications for graduate students dependent on research positions and grants, according to University administrators.

“I think everyone’s concerned about what the model for federal funding is going to be,” said Sally Gressens ’74 M.A. ’77, School of Engineering assistant dean for graduate affairs.

While undergraduate students with documented need receive centrally coordinated financial support through the Financial Aid Office, graduate students are instead largely supported through fellowships and paid positions such as research or teaching assistantships.

“The thinking tends to be that research funds are what is going to propel a student through a [doctoral program],” Gressens said.

“[For] sciences and engineering, you need to have funding otherwise your students don’t have projects to work on,” Arvin added.

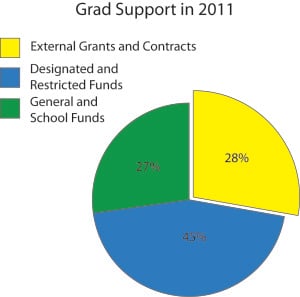

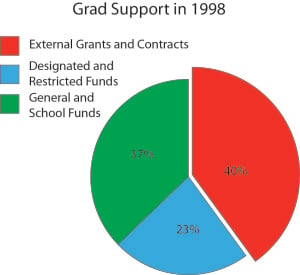

External grants and contracts provided 28 percent of all graduate support in the 2011-12 fiscal year, contributing $85.4 million to a total sum of $300.2 million. Departments more heavily invested in technical fields have historically been more dependent on federal funding.

“We’re concerned that with the federal budget discussions, we might be facing more serious cuts,” said Richard Saller, dean of the School of Humanities & Sciences. “Our allocations are always interacting with federal grants [that are] going to individual faculty members.”

Saller pointed to an ongoing trend in diminished funding from sources like the NIH – which contributed to a $1 million reduction this year in the school’s $90 million graduate aid budget – as symptomatic of potentially more serious issues to come.

“It is a problem,” Saller said. “That doesn’t sound like much, but when you figure in that the cost of living has increased…there’s a 4 to 5 percent decline in real purchasing power.”

A sustained period of fiscal restraint by the federal government may result in a decline in the graduate population

“We may have to settle for what’s been a longer-term base [for H&S], which is around 300,” Saller said, noting that the school admitted 360 graduate students this year.

Saller expressed doubt, however, that the potential for funding cuts will have an immediate detrimental effect on the graduate student population, noting students’ ability to take advantage of other sources of aid within the University.

“We have thought about what will happen,” Saller said. “We’re not going to leave any students stranded.”

Norbert Pelc, chair of the Department of Bioengineering, framed the adjustment in resources available to support graduate students as reliant on individual faculty members to implement.

“At this point, [funding cuts] trickle to the individual investigator level more so than the department level,” Pelc said. “At the department level, we assume that the individual faculty are keeping track of the support they have and aren’t going to take on more graduate students unless they’re confident they can support those students.”

“We all pitch in to help”

For currently enrolled students, the impact of funding shortfalls may be alleviated by the reallocation of resources between schools and departments, as well as through fellowships administered by the Office of the Vice Provost for Graduate Education.

“We try to work collaboratively with the schools in order to help out,” said Vice Provost for Graduate Education Patricia Gumport M.A. ’82 M.A. ’86 Ph.D. ’87. “Where it doesn’t work, we all pitch in to help.”

Gumport cited a diminishing reliance on external grants and contracts in providing student support, as well as a doctoral degree completion rate significantly above the national average, as evidence of the University’s fiscal commitment to graduate students.

“We’re happy to see that we’re less dependent,” Gumport said. “We have a lot to be proud of.”

University-wide fiscal retrenching at the height of the recession, as well as the endowment of 360 graduate fellowships through The Stanford Challenge, have led to a sounder fiscal standing for graduate programs in the event of heavy cuts, according to Gumport.

“The University leadership did a great job of leading us through the impact of the recession, setting a clear path for protecting ourselves and making the necessary cuts,” Gumport said. “The more we have endowed funds, the less vulnerable we are.”

Schools and departments may also contribute more support than is suggested by the University’s standard budget for graduate students – which suggests nontuition expenses of $26,082 through three quarters – in the interest of competing against similar programs at other schools.

“One of the factors in determining [student support] is what other schools are giving to incoming students,” Gumport said.

For some departments, the significance of research cuts may pale in comparison to the impact of the recent recession on private sector investment.

“The School [of Engineering] has a lot of support from industry as well, so we’re affected by the economic climate in any of its pieces,” Gressens said.

Arvin expressed optimism that – even in the case of a significant reduction in federal research funding – the historic success of Stanford faculty in obtaining federal grants might partially insulate departments and graduate students. She did, however, acknowledge that some internal cuts may still be required.

“We think we’re well positioned to maintain our programs,” Arvin said. “But if the federal government decides to make an 8 percent cut across the board, then research funding will be cut by 8 percent which means that, given the amount of money it takes to do research, there is not a good substitute for federal funding so certain programs will have to be smaller.”

For both administrators and faculty alike, however, the continuing uncertainty presents obstacles to effectively minimizing the impact of any cuts.

“No one can predict what will happen,” Pelc said. “In the nightmare scenarios, it would be devastating…If [funding] stays flat or goes down a little bit, that’s the best scenario people are envisioning.”

“[Cuts] will impact graduate education and we will have to make that up from other sources,” Pelc added. “We have to hope for the best and remain competitive.”