On the far west side of campus, tucked between Stanford’s tennis courts and golf course, 30 horses reside on 13 acres of land in one of two campus-owned barns.

These 1,200-pound animals live in spacious and airy stalls with dirt floors bedded in about three-quarters of an inch of Mallard Mini-Flake, a material that makes the floor bouncy and therapeutic, like a gymnastic floor mat. Every room has what Vanessa Bartsch ’99, the head coach of the Stanford Equestrian Team, describes as a “Harry Potter water bucket”– one that magically refills itself after the horse finishes it.

Along with a staff of 16 groomsmen, the 40 equestrian team members are responsible for caring for the horses. They groom and walk the horses every day, and, of course, do the horses’ laundry. Last year, Bartsch estimates the team did 2,000 pounds of horse laundry.

The Farm was once a breeding ground, with the Main Quad area used for grazing horses. The current Red Barn was built over a hundred years ago, although it is not the original barn that was burned down during a fire in 1888.

According to Bartsch, when John Arrillaga ’60 was asked if he chose to fund the renovation of the barn because he liked horses, he replied that he simply wanted to preserve it because he valued the history of the University.

***

The equestrian season goes from October to May, and during that time the horses participate in an event most weekends.

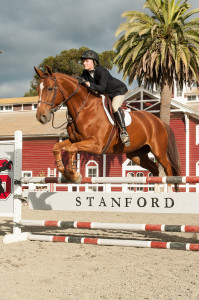

Just outside the barn lies the main show area, where obstacles and open space play home to competition and practices.

According to Alina Benavides ’14, co-president of the equestrian team, the horses are able to tell the difference between practice and performance.

“When the horses see spectators around the fence, they know its go time, and they love to show off,” she said. “They’ll puff up.”

Practice is no simple prance around the field, either. The equestrian team trains with the horses two to five times a week and each team member rides a different horse every day, since at competitions the hosting school provides the horses.

“Everyone is catch-riding, so you really have to learn how to get to know a horse in a minute,” said Claire Margolis ’15, captain of the English discipline within the team. “You have to know how to approach and read a horse well.”

Bartsch usually emails the team with information about which horse they will be riding at midnight the day before an event at Stanford, so that the riders can prepare themselves for the animals’ differing styles– with only one exception.

“If it’s a special occasion, like if it’s the rider’s birthday, I let them ride their favorite horse,” she said.

***

The natural appearance of an equestrian show belies the hard work and preparation that goes into each event. Before each practice, the team members spend about 20 to 30 minutes grooming the horse and picking out the dirt from their hooves before they go into the meticulously organized tack room to gather the horse’s unique saddle and bit.

“Every horse’s back is different and we want to give the horses the most comfortable ride possible,” Bartsch said.

The horses are then walked a bit to warm up before they start their workout, which has different intensities over the week– just like that of any varsity sport.

The horses even have a little workout equipment of their own, called hot walkers, which can accommodate nine horses at once. The machine has arms of metals radiating off from a central pivot point, which contains a motor that moves the arms at various speeds. About six days a week, the horses walk in a large circle either clockwise or counter-clockwise on the device.

“The horses love it,” Bartsch said. “When they switch directions, they love to see who is behind them and touch noses.”

The horses also have a round pen where they can buck and play. Of course, they have to watch out for incoming golf balls flying in from next door.

“Two years ago, our vet got hit in the head with a golf ball,” Bartsch explained. “But golfing neighbors are great– they help us fix our golf carts.”

Aside from golf balls to the head, the horses also have to be protected from the cold.

During the day, they wear a thin blanket over their coats, which are trimmed every year. The blankets are meant to keep the horses warm and prevent growth of their fur, which detracts from dressage points. During the nights, the horses will wear an additional thicker blanket– a “pony parka,” joked Benavides.

As for which horses go in which stalls, Bartsch compares the placement of the horses to Stanford’s freshman year roommate pairings. As herd animals, Bartsch notes, it is important is to figure out where each horse fits in the larger context of a group.

“Sterling is like an alpha mare,” Bartsch explained. “She doesn’t like to be around other mares. And Lenny is quiet and introverted. He also bites so we don’t give him a window. And Lando is strange; he doesn’t like other horses– he just likes people.”

***

With such a wide array of horses, it is no surprise that every rider has a different story to tell.

“Freddy is a weirdo,” said team member Erin Gray ’13, referencing a chestnut horse with a white streak over his head.

“He’s a goon,” Margolis said. “He tries really hard to be good but he throws tantrums sometimes, and he actually hates being brushed, which is weird because all horses love that. But he loves it when you scratch his head.”

And then there’s Handsome, a dark bay Belgian with a little speckle of white between his eyes.

“Handsome is a dork,” Gray said. “He tries really hard to understand what you want from him, but people always say, ‘Oh Handsome, you’re like a water buffalo.’”

While the horses don’t earn awards of their own during competition, at the end of year, the barn has an informal award ceremony. A horse named Ronnie has won ‘favorite of the barn’ for the last few years.

“Ronnie is the love of the barn,” said Gray said. “He’s the biggest of the barn but he’s a sweetheart. He’s a giant teddy bear.”

The bond between the horses and their riders extends well beyond practice and competition. Dressage captain Patrick Freeman ’13 recounted one late afternoon last quarter when he had decided to take a ride on one of his favorite horses, Auzzie, to combat feelings of depression.

Freeman recalls one instance during which he was walking back to the paddock with Auzzie, and the horse leaned his head down for a nuzzle, curling Freeman into a neck hug.

“Sometimes, you don’t need to talk at all to these amazing animals,” he said. “They just know exactly when you need a hug.”