Ayasdi, a data analysis company co-founded by Gurjeet Singh M.S. ’05 Ph.D. ’07 P.D. ’09, Harlan Sexton Ph.D. ’81 and Professor of Mathematics Gunnar Carlsson Ph.D. ’76, has pioneered a new program to help consumers visualize and digest complex data such as sports statistics and genetic maps.

Traditional techniques of analyzing large amounts of data require researchers and businesses to attempt to write code in order to interact with data analysis programs themselves, a job that has often been passed off to computer scientists.

According to Jeff Yoshimura, Ayasdi’s vice president of marketing, the company’s launch transformed an esoteric tool of academia into a “technology platform to [a] scale that any company could utilize.”

Ayasdi’s visualization program, Iris, uses “push-button” functions that take only seconds to display data in 3D structures, compare groups of data or analyze the statistical significance of an event. Ayasdi data scientist Alexis Johnson said that most users can learn how to use Iris in less than a day, making it more accessible than traditional techniques of data analysis.

“Humans are innately capable of recognizing patterns,” Yoshimura said. “It’s just a matter of expressing the data in a way that makes the patterns easiest to recognize.

According to Johnson, Iris allows users to make notes and forward their files back and forth with their colleagues to share insights. Users can also manipulate the 3D form of the data to show their peers different perspectives of the analyses.

Johnson said that Iris has already been applied to real-world problems, including a recent effort to process genetic data from breast cancer patients by separating patients into subcategories based on gene expression.

Though patients with low estrogen receptor expression typically have high breast cancer mortality rates, Iris revealed a subgroup of patients with a 100 percent survival rate. This discovery allowed women with a specific genetic profile to receive targeted treatment.

“What we do is provide a compressed representation of the data set, compressed in a way that retains features and patterns so we can see patterns in very large sets and also flexible in that it can represent complexity,” Carlsson said.

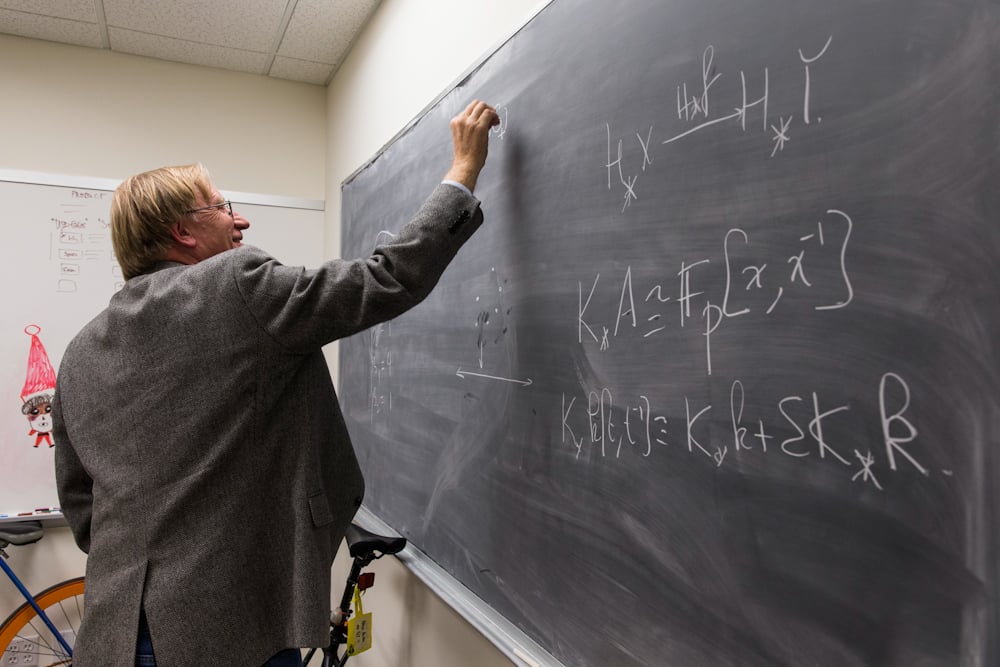

Though Ayasdi was founded in 2008, Carlsson and Sexton met in the 1970s as Ph.D. students in mathematics at Stanford. Singh, who generated many of the algorithms that Iris uses, began working with Carlsson on topological data analysis while pursuing a doctoral degree in computational mathematics.

Ayasdi launched a new website this January and established an office in Palo Alto after receiving $10 million in funding from Khosla Ventures. The company’s 30 employees are currently working on new product applications to make Ayasdi’s technology more accessible.

Carlsson said that the decision to expand Ayasdi beyond research at Stanford was based on the realization that their data analysis could be turned into a usable product. According to Carlsson, creating industrial-grade software within the university would have been very difficult.

“If you’re building very big software packages, it’s sort of not fair to students to have them be involved in writing a lot of code and implementation,” Carlsson said. “Students and postdocs are really here to do their own research and develop intellectually, which isn’t the same as building a bulletproof product.”

Although Ayasdi has since expanded into the private sector, Carlsson said that the Stanford environment has had a significant influence on Ayasdi’s development.

“[Stanford is] the premier place in the world for all sorts of interdisciplinary interactions,” he said. “I myself have taught at other places, I taught at Princeton before this, and in none of those places is the environment even close to comparable.”