The inability of the federal government to avert the “sequester” — automatic and across-the-board spending cuts of $85 billion that came into effect last Friday — will seriously affect the state of ongoing and future research at Stanford, according to University administrators.

In a presentation to the Faculty Senate on Feb. 21, Vice Provost and Dean of Research Ann Arvin estimated that the sequester would reduce Stanford’s projected federal research revenues of $685 million for the 2013-14 fiscal year by $51 million.

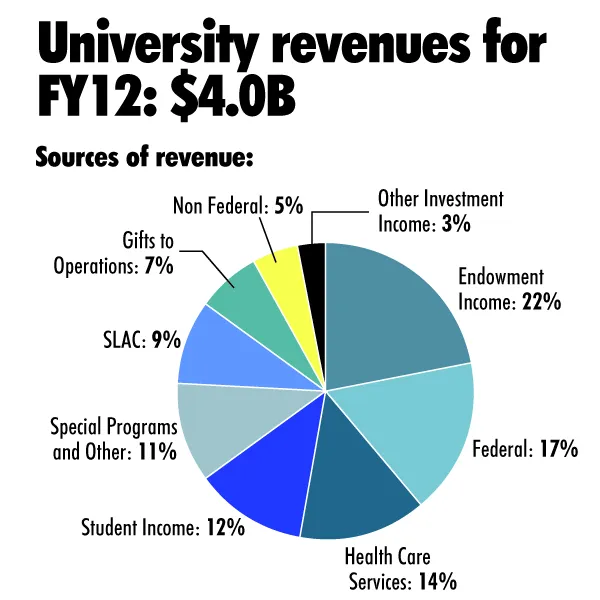

Grants from federal agencies, from the National Institute of Health to the National Science Foundation, make up 17 percent of Stanford’s $4 billion budget and ultimately fund 80 percent of all research conducted at Stanford beyond the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

According to Arvin, the impact of these federal discretionary spending cuts is “quite serious” for the state of Stanford research, forcing faculty to devise a number of measures that will attempt to bring down costs and manage their projects more economically.

“It will affect the amount [of research] and the speed, if you will, the timeline for how quickly the work can be done and the questions can be answered,” Arvin said.

Mr. Adesnik goes to Washington

Ryan Adesnik, Stanford’s Director of Federal Government Relations, articulated his displeasure with the nature of the cuts and the dialogue’s frustrating nature in a phone interview with The Daily from Washington, D.C.

“We’re spending every day communicating the damage that the sequester cuts would inflict on research and education, and the country’s innovation ecosystem,” he said. “We tell them that research and education are investments in the future of the U.S. economy, and that has served us very well over the years.”

Adesnik argued emphatically for federal policies that prioritize research and education funding in acknowledgement of the broader societal benefits produced.

“This is how we drive new technologies of the future, how we educate and train the skilled workforce of the future and it’s the underpinnings of economic future, and it needs to be a federal priority,” Adesnik said.

Additionally, Adesnik asserted that the sequester, ostensibly devised to help manage the U.S.’s burgeoning deficit by providing an unpalatable alternative to Congress passing a more comprehensive piece of deficit reduction legislation, does not actually help fix the situation.

“Sequestration does very, very little to impact the deficit, because the unsustainable growth in the federal budget is being driven not on the discretionary side of the federal budget with the science programs and financial aid, but it comes from the mandatory side, from the entitlements,” he said. “When you’re cutting these investments you’re not helping the deficit problem, you’re just hindering long-term economic growth, and frankly part of how you handle a deficit problem is you have economic growth.”

Adesnik said that the idea of allowing research funding to be diminished at a time where competition around the world is increasing is shortsighted and misguided.

“That’s the absurdity,” Adesnik said. “At a time when the global economy is getting more competitive and other countries are betting on our model, we’re scaling it back, intentionally or unintentionally.”

Peer institutions equally affected

Stanford’s peer universities have been affected in similar ways, with their reliance on federal funding for research leading to potentially grave consequences for the state of research at those institutions.

Princeton University receives roughly $200 million a year from the federal government, and the cuts “could shrink the University’s federally-sponsored research budget by $15 to 20 million for fiscal year 2013 and indirectly diminish its endowment,” according to The Daily Princetonian.

Harvard University anticipates cuts to its $650 million in federal research aid budget and is considering diversification of its funding sources, as well as serious cost-cutting efforts.

The effects of the sequester are also not constrained to research, with federal financial aid programs due to lose crucial funds. According to a White House memo on the specific losses for California residents, “Around 9,600 fewer low income students in California would receive aid to help them finance the costs of college and around 3,690 fewer students will get work-study jobs that help them pay for college.”

According to Director of Financial Aid Karen Cooper, however, Stanford will not be overly affected by these predictions.

“[Federal aid] is a very small portion of the funding that we use to fund undergraduates,” Cooper said. “For this current year we’re spending $128 million in institutional funds on financial aid and we’ll be spending $6 million in federal funds for financial aid, so it’s such a small portion of our budget.”

Because Pell Grants — the majority of Stanford’s federal aid funding — are protected from the sequester, the University should see a marginal impact from the sequester on its financial aid budget, according to Cooper.

“According to NASFA, we would lose around $50,000 from our federal work-study allocation…that should be the main impact to us,” said Cooper. “We spend a little over $2 million in federal work study specifically…so if [funding] is lower than last year by that amount, it actually wouldn’t impact undergraduates. What we would do is reduce the spending on graduate students first.”

Climate of uncertainty

According to Arvin, despite the knowledge of the impending cuts, there is almost no understanding of how the cuts will actually be apportioned for current and future research grants. Instead, that determination has been left to the various relevant federal agencies and internal divisions to decide in the next few months.

“How [the cuts] will happen, we don’t know, but it has to happen within now and the end of the fiscal year, and then it will carry on from there,” said Arvin.

A White House press release claims that, in light of the sequester, “the NIH would be forced to delay or halt vital scientific projects and make hundreds of fewer research awards” and that “the National Science Foundation (NSF) would issue nearly 1,000 fewer research grants and awards”, but as of now there has been no word from those agencies as to when those delays and decreases in grants will be seen.

As things hold as of this moment, “most science agencies will take a five percent hit,” according to Adesnik. He noted, however, that the situation is entirely “variable.”

“If you’re talking from a Stanford-specific perspective, it’s a little to early to tell the extent of the hit,” Adesnik said. “Because there hasn’t been a lot of specific guidance to or from the federal agencies, each agency at least is signaling a slightly different approach for how they’re going to do this. We’re sort of in a wait-and-see mode.”

Lacking solutions

In terms of assessing short and long terms solutions to an impending funding crunch, Arvin offered few answers, citing the enormous expense of conducting fundamental research and Stanford’s dependency on federal research funding.

“If you are successful in getting a grant that gives you $245 [thousand], you’ve only got enough money at that rate to support two trainees and one staff member, and some supplies,” Arvin said. “It looks like a lot of money, but lab research is very expensive.”

“We are lucky we have our donors, but there’s no donor that can substitute $450 million a year of federal research money,” she added. “We don’t have an alternative to federal research funding. Where would it come from, at that scale?”

Despite the difficulty of finding solutions to the impact of the sequester cuts, Arvin emphasized that the cuts come at a time which has been suboptimal for research in general.

“It’s been a very tight funding climate for the last five years,” she said. “I mean, we have been preparing for a long time in terms of the leadership focusing on graduate student fellowships, endowed chairs for faculty, so our strategy really has to be to relieve the burden of costs where we can find a substitute resource.”

In terms of substantive strategies, Arvin said that the essence of any strategy to strengthen research at Stanford would be to cut unnecessary costs and incentivize faculty performance.

“We have to do everything we can to ensure faculty are competitive, and we do that in several different ways,” she said. “We try to offer seed grants, pilot grants internally, for researchers to get preliminary data, we also try to have state-of-the-art shared facilities, because if you have those facilities and instruments available you can have more impact.”

However, Arvin said that cost cutting cannot be a goal unto itself since indiscriminate budget decreases for faculty would diminish the very purpose of much of the research at Stanford — education.

“Keep in mind that our research enterprise is all about education as well,” she said. “Now, we could just take fewer students and hire more research staff and be much more efficient. Are we going to do that? No.”

While the sequester will likely impose substantial damage to research at universities around the country, Arvin emphasized that issues associated with declining federal research spending have been a pressing issue for some time.

“We’ve had to think about the declining federal funding for several years,” Arvin said. “We were thinking about what to do to make sure our faculty remain competitive for research before anybody started talking about the sequester.”