For many, childhood dreams fade into obscurity over time. For some others, however, those ambitions and aspirations remain as fresh as ever, becoming the compasses guiding their lives.

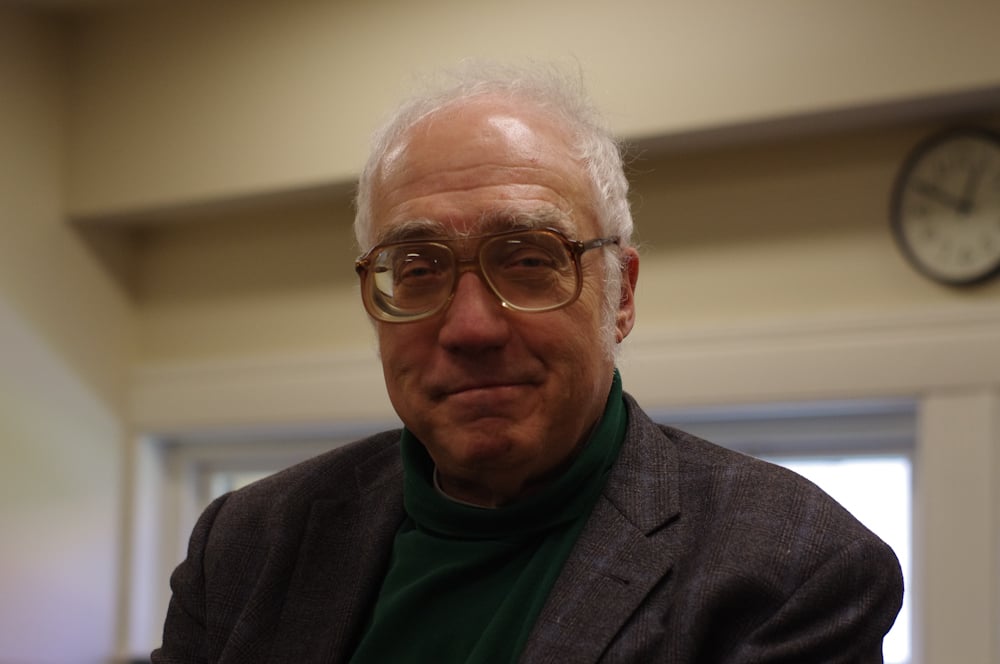

Richard Klein, professor of anthropology, may fall into the latter category, with an affinity for paleoanthropology– the study of evolution through fossils and artifacts–

that began when he was a fifth-grader living in the suburbs of Chicago.

“They would pack kids on the school bus once or twice a year, and take us into the museums in Chicago,” Klein recalled. “One of them was called the Field Museum of Natural History. They had these wonderful diagrams of ancient people sitting around a campfire… and artifacts. I thought it was very interesting.”

Initially, however, Klein believed that the study of fossil forms was something he would outgrow and refrained from taking a related course until later in his undergraduate career at the University of Michigan.

“I didn’t know much about the subject except that it had interested me a long time ago,” he confessed.

During a summer as a graduate student at the University of Chicago, Klein embarked upon his first excavation, spending four months in Spain “excavating a 500,000-year-old site with hand axes and elephant bones.“

His stint in Spain was just the start of an archeological career that would span the globe, with experiences ranging from bleak winters and citizen’s arrests in St. Petersburg to beautiful wildlife safaris in South Africa’s Kruger National Park, all in the pursuit of bones and artifacts.

Klein’s proficiency in Russian led to his choice of artifacts from Russia– then the Soviet Union– as the focus of his doctoral degree. He also spent time in France and Yugoslavia and currently spends his summers doing fieldwork in South Africa, where he has worked since 1969.

“I go there every summer and I dig up some old bones and artifacts,” he said. “I’m mostly interested in bones– I would love to find human ones, but that seems to be not my luck.”

Through his research, Klein developed a special interest in different kinds of antelopes, the animals most abundantly represented in the sites he has excavated. His work offers much of the information gathered to date, for example, on the habits and environments of the Blue Antelope, which became extinct in the 1870s.

“It’s not the center of my research, but I find it very interesting… I’m a kind of an antelope specialist, I guess,” Klein said.

In addition to travelling and teaching, Klein has also written several books about his research, producing– among other works– an evolutionary theory grounded in his study of Neanderthal artifacts.

“I’ve been mainly interested in the last 200,000 years, when people who looked and behaved like we do emerged,” Klein said. “We know they emerged in Africa first, and were confined there until perhaps 50,000 years ago when they moved from Africa and replaced other kinds of people elsewhere, like the Neanderthals from Europe… in probably just a few thousand years… I’m interested in trying to find out why that happened.”

Klein disputed the widely accepted rationale for humanity’s spread, which emphasizes the development of sexual divisions of labor and a resultantly different economic system.

“This makes no sense to me– there is no evidence for population increase,” he added. “The major alternative, and the one that I believe, is that there was genetic or genomic change in Africa.”

Klein acknowledged a lack of support for his hypothesis.

“It’s not a popular idea,” he conceded. “To some people it almost seems like some kind of intellectual Nazism– like you’re suggesting people before 50,000 years ago were not human. I’m not. We know that over the course of evolution, there’s been a huge amount of genetic change. We start with people with brains one-third the size of ours, and then we have us. That’s not population increase, that’s genes.”

Klein expressed optimism, however, that modern science’s ability to compare Neanderthal and modern genes might offer a conclusive resolution.

Since he arrived on the Farm in 1993, Klein has taught HUMBIO 2B: Culture, Evolution, and Society every fall. He also teaches specialized courses on human evolution, which used to attract more than 100 students before the rise of more “technical” subjects caused interests to taper out.

“Two or three years ago, the demand dropped precipitously, as it has for all more liberal-arts type classes… The students are more interested now on coursework that will help them in their future life,” he said. “I sometimes think that it would be better if students came to Stanford when they were 30.”

Klein described the listing of his courses under the anthropology department as “awkward,” saying that most interested students have no intention of pursuing the major.

“In anthropology, they think the courses on evolution are too scientific and they’re more into interpretive work,” he said. “Then you go to biology, and they don’t think it’s scientific enough.”

This ambiguity surrounding the classification of evolution classes has not, however, deterred the enthusiasm for the students who do enroll. Tim Weaver M.A. ’98 Ph.D. ’02 recalled that “it was fun” to be Klein’s student, emphasizing Klein’s scientific integrity.

“I certainly learned a lot from him, not only about the field of paleoanthropology, but also about how to conduct myself as a scientist,” he said.

Ann Horsburgh Ph.D. ’08 echoed Weaver’s sentiments.

“My favorite thing about Richard as a scientist, is that nothing matters more than the work,” she said. “His integrity is absolute. He takes a real interest in his students and concerns himself with their well-being, as well is with the quality of their work.”