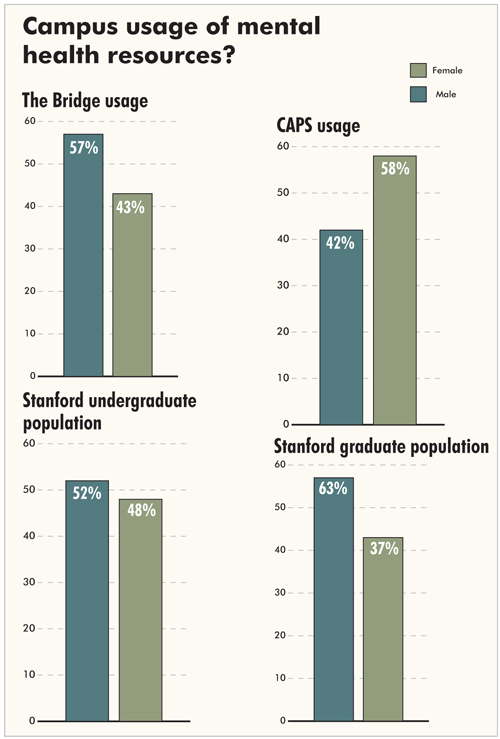

A sustained gender gap in students’ usage of different mental health resources has emerged on campus, according to data from the University’s Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) and the Bridge Peer Counseling Center.

While female students constitute 48 percent of Stanford’s undergraduate population and 37 percent of Stanford’s graduate population, 58 percent of students who have sought assistance from CAPS over the past four years have been female.

“In general, what you find through all medical care as well as in mental health care is that women tend to use services more than men,” said Ronald Albucher, director of CAPS. “In the general population that’s true, it’s true in mental health and it’s true at CAPS also.”

Meanwhile, the Bridge has seen a gender gap emerge in the opposite direction. Patrick McGuire ’14, a Bridge peer counselor, reported that in the 2011-2012 academic school year, the Bridge found that 57 percent of those seeking counseling services were male and 43 percent were female.

“For us it is always encouraging to see the kind of data that is atypical, because it does reinforce the notion that our services are providing something that is not solely provided by CAPS or by professional services,” McGuire said. “It is reassuring that perhaps we do provide a more accessible resource for some populations.”

Addressing the gender disparity at CAPS, Albucher acknowledged several different hypotheses.

“Women tend to interact more with other people, so this model is more familiar and comfortable,” Albucher said. “Men are taught to tough it out and it shows weakness if you have to go to somebody and so I think there are all of those stereotypes that men have to deal with.”

Nikita Desai ’15, co-president of the student health organization Stanford Peace of Mind (SPoM), noted that her group has noticed predominately female interest among students involved with SPoM’s mental health panels.

“I think that just goes back to the unfortunate fact that in our society it is not necessarily considered ‘manly’ to open up and talk about issues that you may be facing, express your emotions and as a result be able to seek out help for it,” Desai said. “I think that they don’t feel as comfortable opening up about things and there is a larger culture of silence in general among males.”

Desai framed the Bridge’s predominantly male audience as indicative of an equal need across genders for mental health support and services.

“Clearly, based on the Bridge counselors’ experiences, there is the need, though not expressed overtly, for mental health services and increased dialogue and openness within the male community,” Desai said.

“Male students may be less inclined where they get to the point to go get services, open up to people about concerns and deal with them, but that’s not to say that those issues don’t exist and that they don’t deal with the same issues,” she added.

Both SPoM and CAPS have mounted efforts to address the gender gap. CAPS has notably sought to increase outreach to the male international graduate student population, a group that is– according to Albucher– naturally predisposed to underutilization of mental health services.

SPoM, meanwhile, is currently working to schedule a mental health panel for the Inter-Fraternity Council (IFC) this quarter. SPoM had a panel focused on the Inter-Sorority Council at the end of fall quarter, which Desai said received a strong reception.

According to Desai, the IFC expressed interest in having such a panel because it recognized the existence of mental health issues among members.

“I think that the key to open discussion is revealing vulnerability and letting other people reveal their own vulnerability and that’s what fosters dialogues,” she said. “In general that is more in line with the female culture than the male culture and I think that leads to some of these issues, but hopefully that can be addressed.”