It seems impossible that any sort of journalistic lede could possibly do justice to Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, when its Communist leaders massacred a quarter of the nation’s people. Faced with a similar display of evil at the Buchenwald concentration camp, the finest reporter of his era could only say: “For most of it, I have no words.” The same most certainly applies to Cambodia — a so-called “Democratic Kampuchea”– from 1975 to 1979. The word “repressive” doesn’t quite capture the sadistic quality of it, and “mindless” ignores its ideological underpinnings. No words can truly express the evil that ran amok under the Cambodian regime, so why try?

It’s not as though words are necessary. The Khmer Rouge was composed of fastidious record-keepers, and today Cambodia remembers its holocaust through all the documents of genocide: photos of the dead, personal histories, false confessions and cabinets full of human skulls. But for those that insist on words, it seems almost more descriptive to use the terms that the Khmer Rouge falsely claimed for itself: “equitable,” when the revolution simply swapped one social structure for another; “visionary,” as though mass murder could be called visionary; “democratic” — and here we are reminded that if a government must call itself democratic, it probably isn’t.

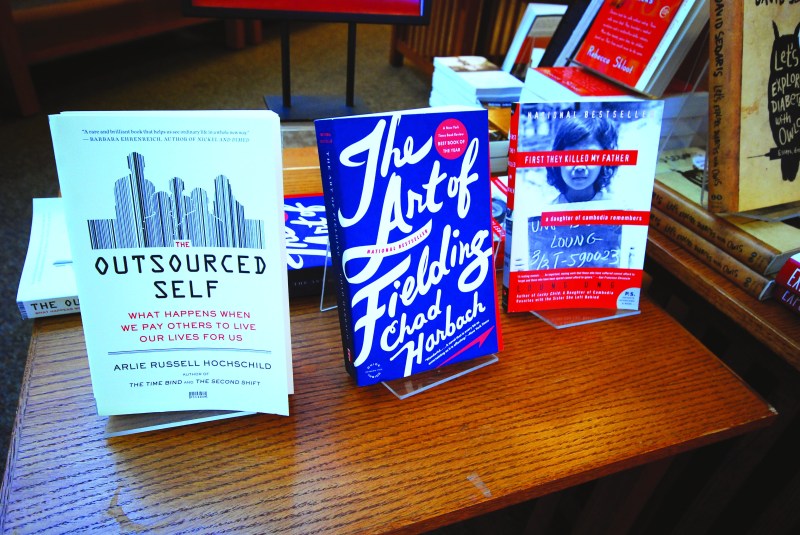

The most terrifying fact about the Cambodian killing fields, though, is that they are nothing new. In her memoir of the Khmer Rouge, “First They Killed My Father,” Loung Ung never mentions the Nazi Holocaust or the Rwandan genocide, but one’s mind drifts inexorably to these crimes nonetheless. As Ung transitions from comfortable city girl to orphan stumbling around the countryside, the ghosts of atrocities past reach out to us. Perhaps that is because the Cambodian genocide occupies an undeservedly minor space in the American psyche; nevertheless, the key point is that its darkness is not alien to us.

Ung does not pretend in any way, shape or form to give a definitive account of the Cambodian horror. Why would she need to? Thrown into starker relief, then, is the greater crime of the human spirit — that even after so many horrors, yet another genocide was allowed to occur.

In this vein, Ung reasons further: If genocide is shocking enough, why not make it more shocking by telling it through a child’s eyes? But the incongruity of a child experiencing such worldly pains, envisioned as the book’s greatest asset, is actually its greatest fault. In a sense, Ung portrays a child far too well. The book reads in the same way that little girls and boys talk — far too much description and thoughts flying every which way, coherent but a dream.

Everything is told; nothing is shown. Paragraphs are disconnected more often than not. Perhaps that is part of the point. But children are really not that good to talk to, and by sounding like a child Ung sacrifices some of her credibility.

The book, put simply, is badly written. Portraying the sheer inanity of the mind of a five-year-old is a very questionable decision on Ung’s part. I hesitate to declare the book not worth reading, because it is; things get rolling as soon as we leave the industrial capital of Phnom Penh, and Ung’s stark description of the faces of evil leaves little more to be desired, if only because of evil’s sheer undesirability.

But readers cannot be faulted for putting the book down within the first 50 pages or so. Ung seems caught between remembering an idealized pre-Communist Cambodia and documenting her trials in the years that followed. The book only declares itself towards the latter when the eponymous father dies. Meanwhile Ung maintains her insistence on the child narrative. In the end, the Wikipedia article on the Khmer Rouge is more informative and more readable — in this case, a picture really is worth a thousand words.

Indeed, with the book complete, the reader is left with more questions than before. From the perspective of a child, war seems totally senseless, and indeed on a certain fundamental level it is. But that fact fails to adequately explain why people rise in revolution and fight wars. Ung describes her pre-Communist life as an idyll, and perhaps for her family it was — well-off, her father a government man, cosmopolitan city dwellers all. The Khmer Rouge ultimately betrayed its own people, but from where did it derive its power? Surely not all Cambodians were as contented with the prewar government as Ung’s family was.

Many people actually supported the Khmer Rouge; the question, then, is why? While nobody expects Ung to support revolution or murder, her refusal to acknowledge the underpinnings of the upheaval that led to darkness makes her life seem not idyllic but cripplingly out of touch. Ung’s passing mentions of the restless countryside are even more frustrating in this regard: She could explain more, but she simply won’t.

In the end, Ung’s description of horror is far more compelling, although — similarly to the exposition — the plot leaves us somewhat adrift with regards to context. At the time, Ung did not know the context of the tragedy surrounding her, but the context does matter to us readers because, unlike her, we can actually make use of it.

Ung argues implicitly that ideology and self-awareness are irrelevant to a child. She is right, but hers is not a children’s book. Any book on the Cambodian genocide, especially one as bluntly titled as “First They Killed My Father,” is a book for adults and an inseparably political book. Ung does her readers a disservice by claiming that the hopes and dreams of people other than her family are immaterial to the narrative. Knowing that a crime occurred is meaningless; knowing how and why it did helps us prevent it from happening again.

Someday, words will be written that fully capture the horror and madness of the Khmer Rouge, that ignoble brother of the Holocaust. Ung’s memory, however, is not that book. Still, one must imagine that when that book is written, its writer will have been standing on the shoulders of the proverbial giants — giants such as a small little girl from a big city who suffered things that we can hardly imagine.