In last Saturday’s Stanford-Arizona State football game, No. 5 Stanford pounded then-No. 23 Arizona State, solidifying its status as a national championship contender. The Cardinal set the tone early by pummeling the Sun Devils at the line of scrimmage and led 29-0 at the half before cruising to a 42-28 victory. Stanford opened the scoring with a lovely tunnel screen pass to explosive junior wide receiver Ty Montgomery, a play that exemplified the smooth execution of the Stanford offense.

Stanford was facing third-and-10 at the Arizona State 17-yard line and needed to get a first down. The Sun Devils dropped five defensive backs to the first-down line, which opened up large spaces up front for short throws. Taking what the defense gave, head coach David Shaw and his play-calling team called a short throw: the tunnel screen.

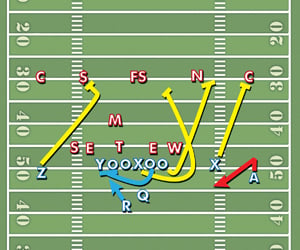

To set the play up, Stanford faked its most ubiquitous run play, “power.” Right guard Kevin Danser pulled from the formation (outlined in blue), ostensibly leading the way for running back Tyler Gaffney (R). Because defensive players are trained to recognize visual cues such as a pulling guard, the play-action deception was a success; it caused Arizona State’s front six to focus on Gaffney. Even without actually blocking anyone, Stanford opened up the middle of the field, and Montgomery could then run wild.

Consistent with the situation, Stanford’s quick passing game got speed in space. As soon as the play began, quarterback Kevin Hogan threw the ball to Montgomery (A), whose job was to use his explosiveness to get into the end zone. Montgomery broke inside to receive the pass then ran downfield, where three Stanford players were blocking for him: receiver Devon Cajuste (X), right tackle Cameron Fleming and center Khalil Wilkes. The successful play-action gave Stanford the numbers advantage — with three blockers against three defenders, Arizona State had no answer for Montgomery.

Stanford’s big linemen and the 6-foot-4, 228-pound Cajuste had a clear physical advantage over the smaller ASU defensive backs (F/S, N, and C). With both numbers and size on their side, the Cardinal players mauled their opponents, accomplishing that rarest of football feats, a “chalkboard play” — a precious moment in which the action unfolds exactly as it was designed to and every player does his job because he is both in position to make his play and physically capable of making that play.

By this point, scoring was a foregone conclusion: Montgomery flew into the end zone, giving Stanford a lead that it would not relinquish. With advantages both in physical strength and schematic efficiency, Stanford’s play illustrated the seamless execution that characterized the Cardinal’s first-half annihilation of Arizona State.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.