Early in the morning of April 18, 1906, Stanford students were asleep in their beds when a massive earthquake shook them awake. The 7.8-magnitude shaker, known as “the Great Earthquake,” lasted for a 20 seconds and caused tremendous damage throughout the Bay Area, including two deaths at Stanford.

Eighty-three years later, history repeated itself. A 6.9-magnitude earthquake shook Stanford apart at 5:04 p.m. Although no deaths were reported on campus, the earthquake caused millions of dollars of damage.

As a result of its California location, the Farm is near two major faults: the San Andreas and Hayward lines. Although a number of smaller quakes have struck campus throughout the years, the Great Earthquake of 1906 and the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake tower above all other disasters in Stanford history.

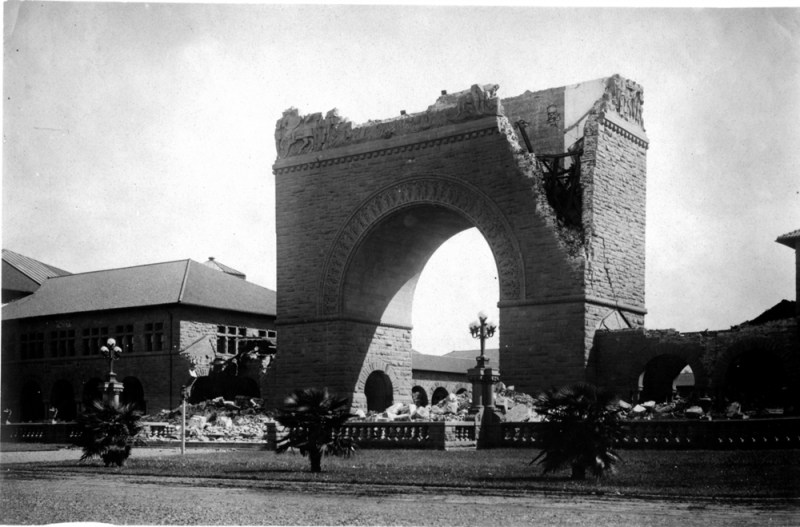

Structures razed and lives lost

At approximately 5:07 a.m. on April 18, 1906, the Great Earthquake struck Palo Alto.

According to a Daily Palo Alto (now The Stanford Daily) article titled “Magnificent Structures Razed and Two Lives Lost” published the day of the earthquake, “the first shock in Encina Hall brought 300 scantily clad men into the corridors in a mad rush for safety and open air” while “the cries of the victims buried in the ruins of the collapsed third floor were plainly audible.”

Two men perished in the quake: Junius R. Hanna ‘08, and Otto Gerdis, a campus fireman. Hanna, a resident of Encina Hall—then an all-male residence—was crushed to death when a chimney fell through the building’s roof. Gerdis was in a campus utility tower attempting to turn off the school’s steam and electricity circuits when the building collapsed on him. Six other students sustained major injuries.

David Starr Jordan, the University President at the time, released a statement in the Daily Palo Alto regarding the university’s next course of action. He began his commentary by focusing on the sad, but slightly uplifting, circumstances of Hanna and Gerdis’ deaths: Despite these tragedies, he said, “had the earthquake taken place in the daytime, the loss of life would have been appalling.”

Jordan anticipated that the damage would total $2.8 million ($73.7 million today) and hoped that “old[er]” and “rich” alumni would contribute to the reconstruction efforts. Jordan’s prediction was roughly $1 million over the mark.

According to Daniel Hartwig, the University’s current archivist, there was around $1.75 million (over $44.7 million today) worth of damage across campus. Damage in the inner quad—the construction of which was had been scrupulously overseen by Leland Stanford before his death in 1893—totaled to roughly $50,000.

The other sections of campus, including the outer quad, Memorial Church and the museum experienced approximately $1.7 million of damage because they were not as adequately prepared for earthquakes.

“They started [reconstruction] on the outer quad that summer, including the library, the physics corner and the assembly hall, finishing renovations a year later,” Hartwig said. “Rebuilding the church, which was badly damaged, was put off and was much more expensive, started in 1908 and lasted until 1917.”

The day after the earthquake, Jordan closed the University for the remainder of the quarter and sent all students home. However, many chose to stick around for the summer in order to volunteer for relief efforts in San Francisco. According to Hartwig, Stanford students participated in Camp Stanford in the City, a project that helped provide food and build shelters for people affected by the earthquake.

The school did not reopen until late August of that same year when fall quarter commenced and the seniors, known as “the Calamity Class,” were able to graduate.

Despite the need for extra income, the college continued to offer free admission to all students, a practice that was discontinued in the 1930s, and received most of their renovation funds from private donations.

The quake televised ’round the world

The Loma Prieta Earthquake of 1989 struck on Oct. 17, just before the third game of the 1989 World Series. Coincidentally, it was the Northern California teams, the Oakland Athletics and the San Francisco Giants, that were competing for the championship.

Richard Gillam ‘65 Ph.D. ‘72, a professor of American Studies, was at home watching the game when the 6.9-magnitude quake hit the Bay at 5:04 p.m.

“My daughter was down the street, and she came running out of the neighbor’s house and back to home,” Gillam said. “It took some small amount of time to calm her down and convince her that the world was not falling.”

In contrast to the 1906 earthquake, the disaster struck at the end of the day, and so most students were dispersed across campus.

Although Loma Prieta did not result in nearly as much destruction as the 1906 disaster, renovation fees totaled $160 million (nearly $302 million today). No deaths or injuries were reported, although students and staff alike certainly felt its seismic waves.

Mark Lawrence ‘67, KZSU’s chief engineer, was working at the radio station’s transmitter site near the Dish when the quake hit. In the middle of tinkering with a piece of equipment, Lawrence suddenly fell on his rear end. After realizing what had happened, Lawrence rushed back to the station’s headquarters in the basement of Memorial Auditorium to assess any potential damage.

Back at the station, a broadcaster announcing a news report had rapidly adjusted the content to include word of the quake. KZSU was the only radio station on the air in the Bay Area—if only for a few minutes.

“The reason for that is not only that we have a backup generator, but also battery power supply on the transmitter,” Lawrence said. “We didn’t lose power on campus, but we did lose power at the transmitter for half a day.”

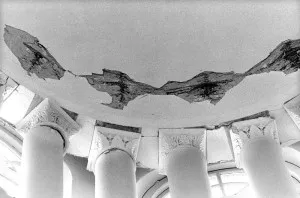

Like the 1906 earthquake, however, Memorial Church and the main library (now Green Library) were two of the most damaged locations. The church was closed for renovation until 1992, and the library didn’t reopen until 1999.

In the quake’s immediate aftermath, many buildings were evacuated until a team of engineers could determine whether or not they were safe to occupy. Fortunately, many of them were.

Despite the damage, Monica Moore ‘71, a longtime campus administrator, found a silver lining in the way that the campus united after the disaster. Smaller programs shared office space and faculty held classes outside—students even utilized construction spaces as outlets for creativity.

“After the earthquake, they put up these big plywood supports on the arches, and then the Studio Art students came out and painted them,” Moore said. “They were kind of big, bright and colorful, sort of abstract mostly, and I just thought we should keep them there as public art, but they took them down once they retrofitted the arches.”

Preparing for the future

In the years since Loma Prieta, Stanford has done much to ramp up its earthquake safety precautions, particularly in light of scientific predictions for another shaker in the near future.

After the disastrous earthquake that struck Honshu, Japan, on March, 11, 2011, Stanford seismologists became concerned with the Hayward fault, which is reaching the end of its average fault slip cycle of 140 years.

“After the 1989 Earthquake, Stanford became much more adamant about being earthquake safe,” Hartwig said.

Stanford’s next step towards earthquake preparedness will be demolishing Meyer Library, a campus staple for late-night studying since 1966.

“[Recently], there was analysis done and the cost was determined to be prohibitive, so rather than upgrade and reuse Meyer, it was better to tear it down,” Hartwig said.

For the Stanford community, the end of Meyer, which university officials have proposed to demolish in 2015, will mark a step towards earthquake preparedness, even if such disasters can never be truly predicted.

Contact Molly Vorwerck at mvorwerc ‘at’ stanford.edu.