Stanford football has played four ranked opponents in its last six games, but it will face by far its biggest test yet on Thursday against the third-ranked Oregon Ducks. Stanford is 2-2 in its last four games against Oregon, but what most people seem to be talking about is Stanford’s 17-14 upset victory in Eugene last year. But even though the great Chip Kelly left Oregon for the Philadelphia Eagles after last season, Oregon has hardly missed a beat under new head coach Mark Helfrich, and the Ducks’ offense is extremely difficult to stop.

The principles underlying Stanford’s defeat of the Ducks were discipline in the run game, excellent safety play, conservative pass defense and defensive penetration along the offensive line. With its speed, Oregon thrives on opponents’ mistakes, and last year, Stanford simply didn’t make them. Indeed, by taking a page from the playbook of the legendary 1985 Chicago Bears defense, Stanford actually forced a few mistakes of Oregon’s own.

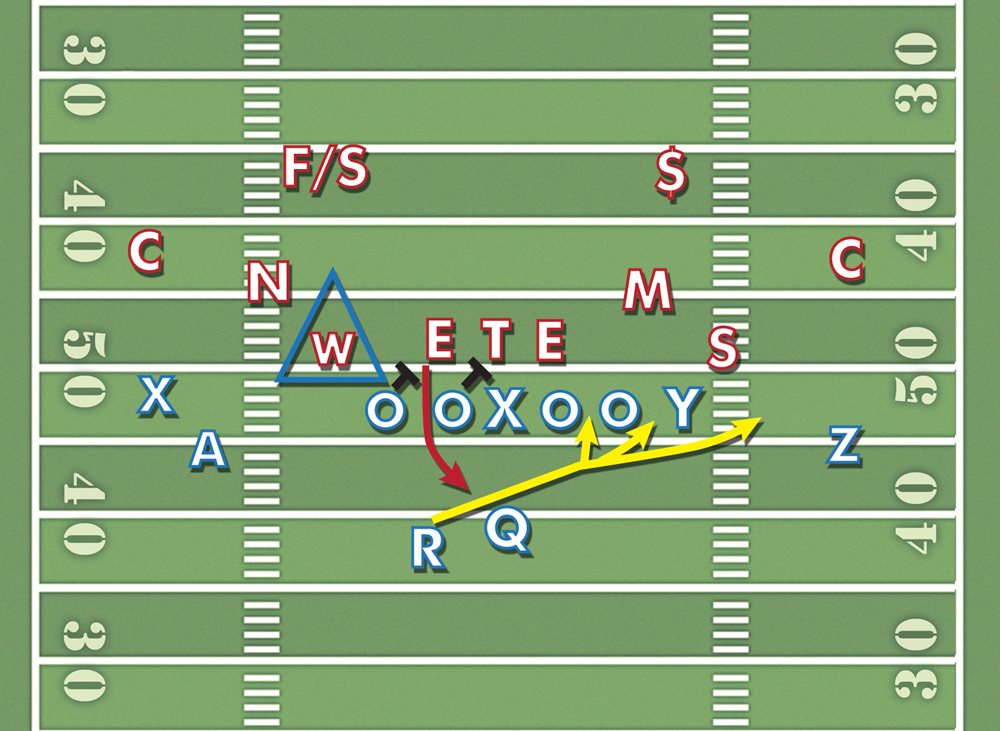

This graphic depicts Oregon’s most ubiquitous running play, the outside zone: a play that presents opportunities to attack both downhill and to the outside (outlined in yellow). The offensive linemen step in unison toward the right (or the left), blocking the first men they see to their right, double-teaming when they have the opportunity and driving toward the linebackers. The running back patiently waits for a hole in the defense and hits whatever running lane he finds. Additionally, Oregon’s quarterback Marcus Mariota will almost invariably option off a player (the blue triangle), neutralizing him by threatening to run in his direction. The real danger of the option, however, is not Mariota’s speed but the fact that it frees up an offensive lineman to block a different defensive player.

By spreading out its offensive line, Oregon also stretches the Stanford defense, so that if Stanford’s players get out of position, the Ducks will have extremely wide running lanes. (Offensive line splits are exaggerated for clarity.) Spreading the field to minimize the defense’s margin of error has been a boon for the Ducks, who have routinely been among the nation’s top offenses since adopting the spread option attack. After Stanford aligned its defensive linemen in its guard-center-guard Bear front (a highly aggressive tactic popularized by the aforementioned Bears) last year, however, the Ducks’ spread actually allowed Stanford to break up the Oregon line.

Here, Stanford knew that by zone-blocking rules, Oregon’s linemen would block only players to their right. The Cardinal lined up three players over Oregon’s guards and center, forcing one-on-ones for these players, and aligned its players to take advantage of the zone rules. Here, the backside defensive end (E, red arrow) was shaded just outside the left guard, head-up with the guard’s left shoulder. Because the end is technically to the left of the guard, the guard will block the defensive tackle (T) and pass off the end to the left tackle.

Because of Oregon’s wide line splits, the tackle had a very difficult block to make: Stanford’s end was nearly a yard away and slanted away from him as well. Notice that Oregon’s outside zone resembled Oregon State’s slide protection from last game: With the Bear front, the geometry of the play was the same. Just as fifth-year senior defensive end Ben Gardner knifed through the Oregon State line to sack Sean Mannion last week, so Stanford’s line had a free shot at Mariota (see the red arrow) as he prepared to hand the ball off to one of Oregon’s dangerous running backs.

This alignment stretched Stanford’s front six more than I’d like, and last year the Ducks had some success when they attacked up the middle — where Stanford only had one second-level defender — instead of taking the ball to the outside. However, when the Oregon run game was pushed towards the middle, Stanford’s safeties ($ and F/S) were free to clean up anything that came through, allowing some gains but preventing long touchdowns.

With the outside runs held in check, the only big-play threat Oregon had left was its downfield passing game, and Stanford’s conservative Cover 4 coverage kept a lid on Oregon’s receivers as well — Oregon quarterback Marcus Mariota had an uncharacteristically shaky night, with only two completions of 20 yards or longer the entire game. Overall, Stanford allowed only two Oregon scores on fifteen drives.

The success of Stanford’s defensive front was undeniable: By generating penetration on the line of scrimmage, Stanford shut down Oregon’s best running play, and the Ducks were hobbled all night. How Oregon responds to the Bear front on Thursday will hugely influence Oregon’s national championship hopes — and perhaps keep Stanford’s alive.

Watch out for an extended preview of the Oregon offense later in the week. Readers are strongly recommended to follow the mysterious cabal of football geniuses that operate Fishduck.com — especially this piece here: http://fishduck.com/2012/11/how-stanford-stopped-the-oregon-offense-2.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.