“Give me the statistic that makes a guy take an extra rep in the offseason because he is sick of being on a losing team, or makes him work that one bit harder to make the game-saving tackle as the backside safety.”

Football Editor Joey Beyda gave me that challenge earlier this week while we were debating whether or not the Cardinal is due for a loss against USC after winning each of the last four matchups.

The question, in its entirety, boils down to whether teams become more likely to beat their rival after losing to that rival for a few years in a row. Joseph thought they were; I thought they weren’t.

For the analysis, I looked at the last 30 meetings of each of the top-25 college football rivalries, according to Yahoo! Sports. I replaced LSU-Arkansas, which is the only rivalry of the 25 that hasn’t been played continuously over the past 30 years, with Stanford-USC in honor of tomorrow’s big game. By looking at every winning streak in each of the rivalry, I calculated probabilities of a team winning a rivalry game given how may consecutive losses it had suffered going into that edition of a game.

Due to data constraints, I counted streaks of five or more losses as just five losses in the probabilities. This intuitively gels with the question, as there are very few college football players who have six years of eligibility, so any player on a team with at least five consecutive losses to its rival has only been a part of the team while it is on a losing streak, so a streak of more than five games is equivalent to streak of exactly five games in any of the players’ minds.

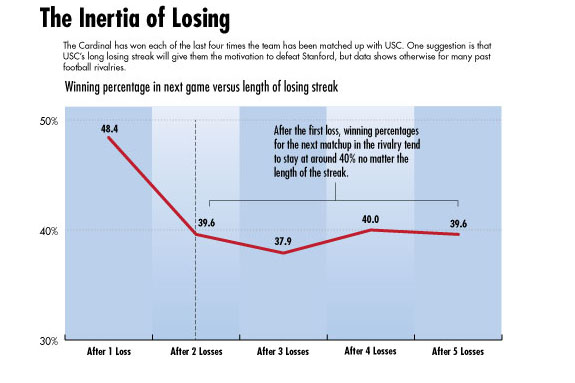

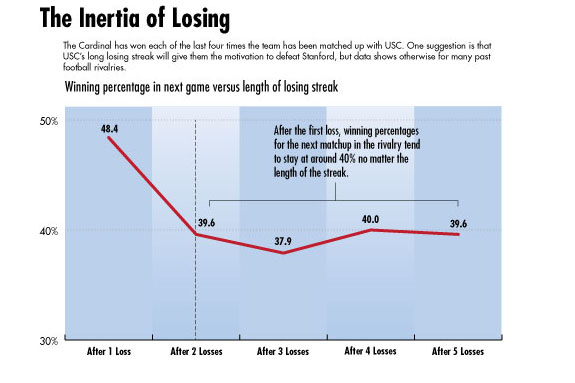

The results of this data are intriguing. At first, it seems that poor Joey Beyda is very wrong. As the chart shows, there is a negative correlation between length of a losing streak and winning percentage for that team. In simpler terms, the longer a losing streak that a team is on to its rival, the lower the chance that the “underdog” will win the next game.

Looking further into the data, it is worth noting that at no point does the winning percentage drop below 37.9 percent (which corresponds to a losing streak of three games). That certainly speaks to the competitiveness of the rivalries on the list — even during a stretch of dominance by one team the underdog still has a solid chance of scoring an upset.

This conclusion gets even more credence when you ignore losing streaks of only one game. Ignoring this data makes sense in the context of the rivalries chosen. As most of these rivalries are very competitive and alternate between the home stadiums of both teams involved, the most likely outcome would be each team winning at home for corresponding losing streaks of one game each. The data supports this hypothesis, as a team on a one-game losing streak has almost a 50-percent chance (48.4 percent, to be exact) of winning.

Looking at the remaining data, the downward sloping trend disappears. For losing streaks of two games or longer, the team on the downturn has around a 40-percent chance of winning the next game. This holds whether the streak is of two, three, four or five or more games.

This result has many different interpretations. The one most relevant to the Stanford-USC matchup this Saturday: Don’t think Stanford is in the clear because it has a four-game winning streak — USC is just as likely to beat the Cardinal this year as it was in each of the last two seasons.

Curiously, this 40-percent chance corresponds almost exactly to what current models that relate point spreads to win probabilities would say about tomorrow’s matchup: a 3½-point underdog (like USC) has approximately a 40-percent chance of winning the game.

So while these results are limited in scope, this quick analysis has uncovered some interesting trends for further exploration and, hopefully, has shined a bit of light on what to expect tomorrow night.

Contact Sam Fisher at safisher ‘at’ stanford.edu.