Stanford’s national championship hopes disappeared on Saturday night in the Coliseum as Southern California defeated Stanford 20-17. USC played well, but even after a flood of miscues — inopportune penalties, turnovers and poor decisions — the Cardinal was still in position to drive down the field for the winning score. However, junior quarterback Kevin Hogan then threw a deflected interception to Trojan safety Su’a Cravens with just 3:03 remaining in the fourth quarter, and the Trojans took advantage of a short field yet again to set up Andre Heidari’s game-winning 47-yard field goal.

Before the interception, Stanford had plenty of time to set up a game-winning field goal of its own. The Trojans’ run defense had been ground to bits in the third quarter. After a solid 8-yard pass to junior wide receiver Jordan Pratt had given Stanford a second-and-2 situation at the Stanford 40-yard line, the Cardinal knew that it could probably run for a first on third down if needed. So Stanford took the opportunity to throw.

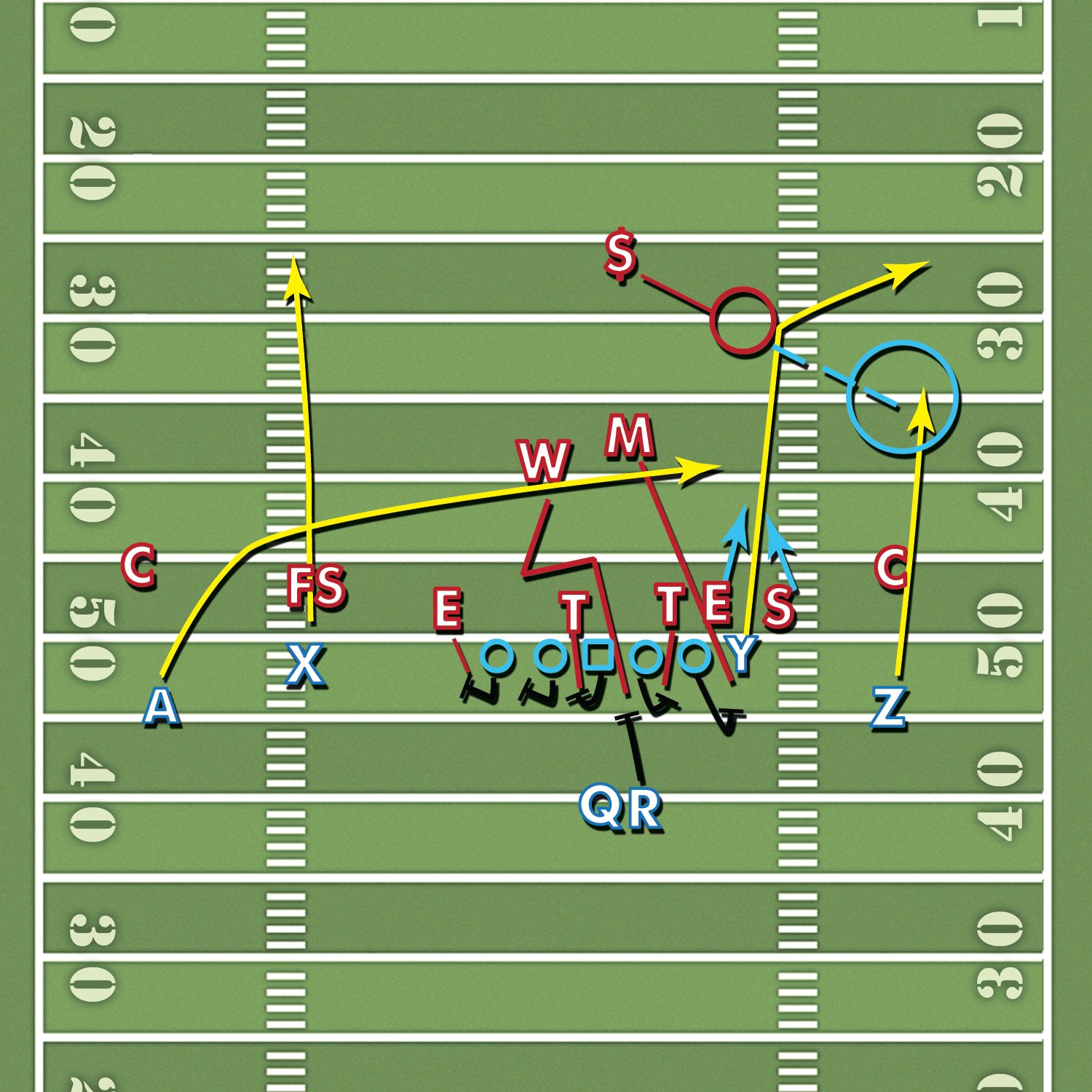

Stanford called two passing concepts, a drive on the left side and a smash on the right. The routes in the drive set a pick downfield, allowing a Stanford receiver to spring free, and the short cross was an outlet for Hogan in case he had to throw. The smash was designed to put a bind on the Trojan cornerback by attacking his area with two players, forcing him to leave a player open.

I don’t normally talk about pass protection because I have only so many words in this column. But here it was especially critical. Stanford called a 2-Jet/Frisco protection, a common line call in David Shaw’s West Coast offense. This meant that the center and the left side of Stanford’s line slid left, covering gaps instead of men. Meanwhile, the right side of the line did the opposite. This allowed Stanford to bring help to the left, where Stanford was expecting a blitz to Kevin Hogan’s blind side.

The play started inauspiciously. USC defensive coordinator Clancy Pendergast is a daring risk-taker with his blitzes, and Stanford got overwhelmed. Sophomore left tackle Andrus Peat made a mistake with his footwork, ended up in an extremely wide stance and didn’t have the physical leverage to handle USC’s weak side defensive end. Peat has been very good this year, so when senior left guard David Yankey slid left with him without a threat in sight, Yankey helped center Khalil Wilkes with the weak side tackle instead of Peat, and by the time he realized Peat was in trouble, it was too late.

On the right side of the line, instead of blitzing the strong-side end and linebacker (E and S), USC actually jammed senior tight end David Dudchock (Y), preventing him from getting a clean release and acting as a safety valve for Hogan. It didn’t matter on paper as Dudchock was running a corner route to the sideline, but the jamming delayed Dudchock and he couldn’t get the necessary depth downfield to isolate his defender, Cravens ($). This will become more important later. By taking senior right tackle Cameron Fleming’s man assignment out of the blitz, USC also froze Fleming for a second as he figured out what was going on, giving the blitzing middle linebacker (M) a window to get into the backfield.

The key to this play was the weak side linebacker’s (W) read blitz, the Check-Rain. If the center pass-blocked to the right, he would attack the left, in the gap between the occupied left tackle and guard. If the center pass-blocked to the left, as happened on this play, he would attack the right, between the occupied center and right guard. Either way, W would be free to rush. Stanford had anticipated this blitz by using senior running back Tyler Gaffney (R) in pass protection, but although Gaffney read the blitz correctly, he failed in his execution; his poor footwork and leverage allowed the W into the backfield anyway.

With three simultaneous failures, the pocket collapsed almost immediately and Kevin Hogan (Q) panicked. Jordan Pratt (A), Hogan’s safety valve, was wide open on the crosser for an easy first down, but Hogan wasn’t looking at him. Junior wide receiver Ty Montgomery (Z) looked wide open but was ineligible after being pushed out of bounds on the comeback. Hogan, already going down, desperately chucked a grenade in Montgomery’s general direction.

Montgomery tried to reach back for the ball when he didn’t really have a chance and deflected the ball towards Dudchock. And the ball still would have fallen harmlessly to the ground if Dudchock had not been jammed and taken a more direct route to the sideline to compensate for his poor timing. His route drew Cravens close to Montgomery — and thus in position to make the biggest interception of his life. I don’t mean to demean USC’s performance, because the Trojans still had to execute, and they did. But for Stanford, this play was a perfect example of Murphy’s Law: “If it can go wrong, it will.”

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.