Stanford beat Notre Dame on Saturday for the fourth time in the teams’ last five contests. The 27-20 result was surprisingly close — Stanford had been favored to win by over two touchdowns — but a win is a win, and the Cardinal is now 14-5 in one-possession games since David Shaw took over as head coach.

The Cardinal is very effective at beating its opponents into exhaustion with a consistent running game. Against evenly matched opponents, fatigue late in the game is often the deciding factor. Conversely, when Stanford has lost, it has typically been when opponents have stacked the tackle box with eight players to overwhelm Stanford’s run-blocking schemes. Quite frankly, at some point, a team can only punish eight-man boxes by throwing the ball; while people love to condemn pass-happy teams for not being able to run the ball, the same holds for run-heavy teams that cannot throw it.

Kevin Hogan was not elite on Saturday night, throwing two interceptions, but he was good enough (8.8 yards per attempt) to make passing a viable option. That, in turn, opened up opportunities in the run game such as Anthony Wilkerson’s 20-yard touchdown run in the third quarter.

Stanford was facing third-and-9, so Notre Dame had to be thinking “pass” anyway. But the Cardinal was in the Notre Dame red zone, and a decent run might set up fourth-and-manageable. Even if the run failed, a field goal was a reasonable consolation prize. Notre Dame defensive coordinator Bob Diaco opted to hedge his bets and put his strong safety ($) at an intermediate level of the defense — not inside the tackle box, but close enough to hopefully avert a disaster. However, Notre Dame could not outnumber Stanford at the point of attack.

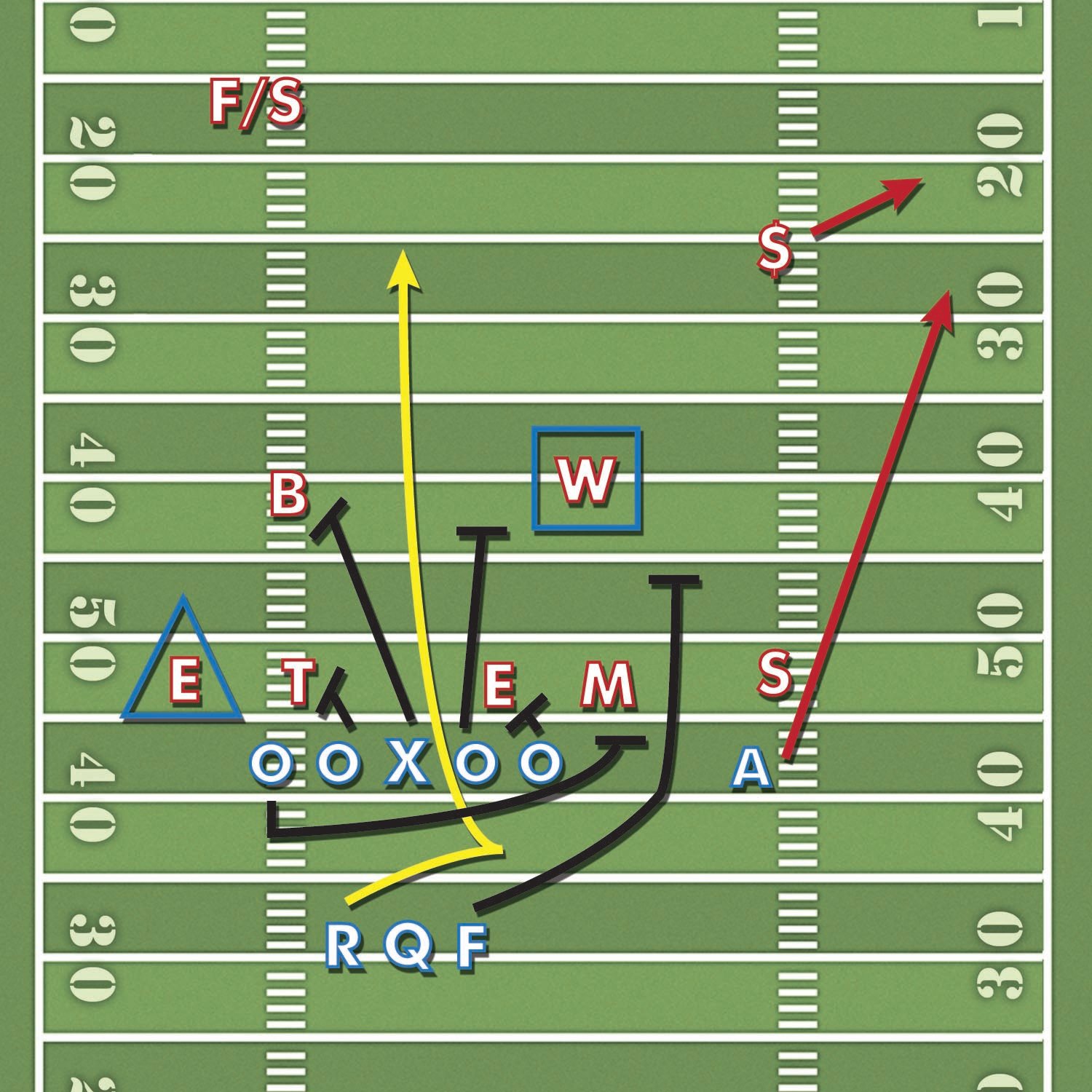

Against this alignment, David Shaw called a very interesting run play: a read-option trap. (Wide receivers and cornerbacks have been omitted for clarity.)

The read-option component of the play was quite typical. Quarterback Kevin Hogan (Q) read the backside defensive end (blue triangle); if the end crashed the handoff, Hogan would take the ball outside, and if the end stayed home, he would hand the ball off to Anthony Wilkerson (R). This allowed left tackle Andrus Peat to block somebody else.

This was not, however, the ubiquitous zone read. Both the classic zone read and this option play option off of a backside defender: The play goes one way, and the quarterback basically threatens a bootleg to the opposite side. If the defender correctly sits back and forces the handoff, the offense’s free blocker is on the wrong side of the field — if the defense aligns properly, there is very little that the blocker can do to affect the outcome of the play. Stanford took advantage of this many times against Oregon.

How did Stanford use Peat, then? The Cardinal had him run the trap.

The trap block punishes aggressive defenders by initially leaving them unblocked and then sideswiping them with a blocker pulling across the formation. A defender not actively watching for the trap would easily get caught off balance. The unlucky defender in this scenario was Notre Dame’s middle linebacker (M), who was setting the edge of the formation. By pushing him out of the way with Peat, Stanford hoped to open up a massive hole in the defensive front. Fullback Ryan Hewitt (F) went along with Peat to lead block for Wilkerson in case Notre Dame decided to blitz the hole.

The best part of this play, however, was that Stanford took advantage of Notre Dame’s alignment to create a perfect cutback lane as well.

Notre Dame wasn’t expecting a run up the middle on third-and-long, so the Irish had left it open. The Irish only had two linebackers behind the line, and because center Khalil Wilkes wasn’t being covered by a lineman, he immediately hit the second level, blocking the first defender to the left (B). All that was left for Wilkerson was to read Notre Dame’s weakside linebacker (W, blue square). If the W blitzed through the cutback gap, Stanford would have three blockers on two Irish defenders on the playside, leaving Hewitt free to block a safety for approximately a 10-15 yard gain. If the W went outside to meet Hewitt, Notre Dame had nobody left for a cutback up the middle.

Mathematics opened up possibilities, and against a great offensive line like Stanford’s, Notre Dame going with two high safeties might as well have been the kiss of death. Bob Diaco thought that he was being conservative by putting two safeties deep. But Stanford didn’t just convert the third down; it scored.

Wilkerson correctly read the play and cut upfield. After receiver Devon Cajuste (A)’s run drew away Notre Dame’s strong safety ($), only the free safety (F/S) was left between Wilkerson and the end zone. Focused on the passing game, the F/S was too far away and couldn’t get to the run in time. Wilkerson hit full speed by the time the safety realized what was going on, easily broke the tackle and coasted into the end zone.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.