They explain why Mitt Romney was labeled a flip flopper in the 2012 election. They explain why our politics have swung so dramatically to the extremes of the political spectrum. And they may well predict whether the Democrats control the White House again after 2016.

They, primaries and caucuses, are the process by which political parties nominate candidates for office.

Yet the terms “primary” and “caucus” are only important to three groups of people: (1) hopeful candidates such as Mitt Romney, (2) political junkies like this writer and (3) high school students studying for a civics exam as you once did. While these may seem like three disparate groups, their relationships — or lack thereof — have a profound impact on this country.

The vast majority of the country loses interest after their high school exams, allowing those like me to control the process. For Republicans, this has meant that nomination seekers must cater to the Tea Party.

While Mitt Romney was campaigning for the nomination, he faced seven serious contenders in 20 official debates. This, in addition to the millions of dollars spent against him by his own party, made him unable to sway enough voters to his camp later on in the actual presidential race. Right now, it seems, winning the nomination and the general election are mutually exclusive for Republican presidential candidates — a problematic situation for a healthy democracy.

Thankfully, GOP leadership has recognized their dilemma and has established a plan to fix it, according to CNN. First, there will be fewer official debates and participation in outside “forums” will be deterred. Second, the RNC will enact penalties against states that move their primaries earlier. Third, primaries that take place around Super Tuesday will now award their delegates proportionally; avoiding a winner-take-all system means that consistently strong candidates won’t face as significant challenges from challengers who sputter out after winning one state.

If passed by the RNC Rules Committee, this plan will make it more difficult for extreme viewpoints to leverage their way onto the main stage of national debate. Those most in line with states’ Republicans will get the nod.

Right now, that person is Chris Christie, who leads national polls by 6.2 percentage points, according to Real Clear Politics. State GOP leaders say that his recent controversy is unlikely to affect voters. Nevertheless, Rand Paul, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio are not far behind.

While it’s an admirable plan, there is a better way to reform primaries to encourage more moderate candidates: the jungle primary.

The jungle primary, more formally called the nonpartisan blanket primary, removes parties from the primary process. Rather than advancing one Republican and one Democrat (in addition to a slew of third parties), this system allows the top two vote-getting candidates to advance, regardless of party.

In more liberal California, where this system was instituted after the 2010 election, Democrats are likely to earn those spots. Take, for example, the 15th Congressional District, just east of Stanford.

In 2012, two Democrats faced off in the primary: incumbent Pete Stark and Eric Swalwell. Stark beat Swalwell by 6.1 percentage points in the primary while Swalwell defeated the third contender by 14.3 points. In the general election, Swalwell won because his more moderate positions appealed to Republicans, who had no one from their party to support.

In the district just south of Stanford, CA-17, incumbent Democrat Mike Honda is facing a 2014 challenge from another Democrat, Ro Khanna.

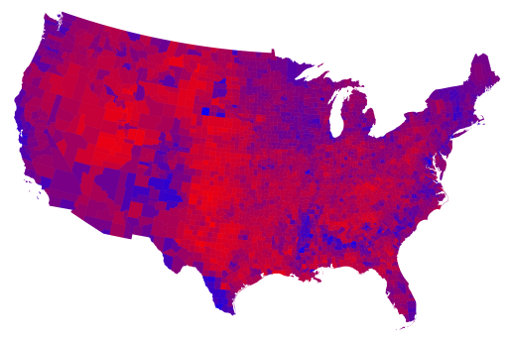

California, Louisiana and Washington have already enacted this system. Purple districts would especially benefit from their states following suit. Interestingly, many districts fit this description, as a map made by Mark Newman of the University of Michigan demonstrates.

Even if national reform of the Republican primary is likely to happen and will encourage more moderate candidates, nonpartisan primaries would do many states and voters more good.

In the end, however, the real answer lies with you and me.

While in Washington D.C., I met with a moderate member of Congress for class. I asked her why there are not more moderates in Congress. Her response was simple: Voters don’t elect them.

Though one is more far reaching, both of these changes will enable centrists to have a greater voice in elections. But, they will not just hand out this leverage; moderates and independents must be more active.

Young people especially have been disaffected by the recent hyper-partisanship. Our retrenchment from politics has not encouraged reform of primaries. But the solution is not to remove ourselves further. Indeed, it is the opposite. If we want change, we must make it ourselves.

Contact Nick Ahamed at [email protected]