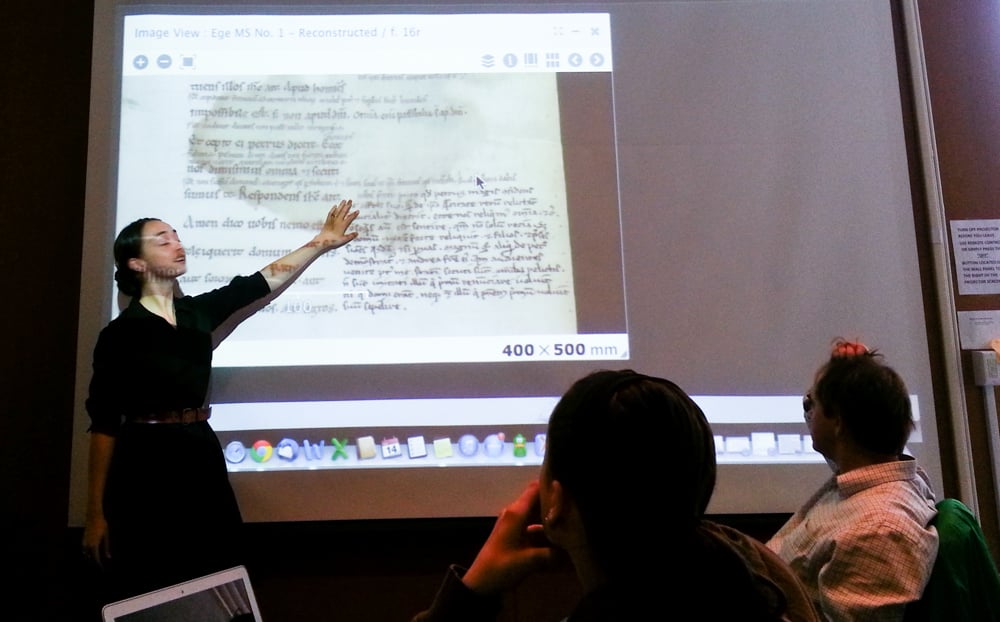

Students convened this past Friday at Meyer Library to use digital technologies in the study of medieval texts and fragments, in the inaugural meeting of the University’s Medieval Manuscripts Club.

Digital Medieval Manuscripts Fellow Bridget Whearty Ph.D.’13, who along with Digital Medieval Projects Manager Ben Albritton runs the club, framed the group as a means of satisfying varied student interests in medieval literature—from those held by classics majors to those of “Game of Thrones” fans—and giving students the opportunity to discover new passages.

“There are these amazing opportunities to work with these books that have never really been studied or [haven’t been] studied as much as, say, Chaucer,” Whearty said. “So what do we do to get it in people’s hands and get them playing with it?”

Whearty emphasized the club’s open nature, noting that participation requires neither previous knowledge of ancient languages like Latin or Greek nor experience with paleography (the study of ancient writing systems).

Elaine Treharne, co-director of Stanford’s Center for Medieval and Early Modern Studies, said the club reflects a general effort “to enhance the medieval division at Stanford” and to help students understand the relationship between primary source material and modern editions.

Treharne also singled out students’ use of Transcription Paleography and Editorial Notation (T-PEN) software—which offers a constantly expanding database of images of texts from institutions around the world—to examine manuscripts as a “fairly new” twist in a broadly practiced area of study.

Albritton, who also manages Mirador, Stanford’s open-source manuscript viewer, described the club as part of the larger goal of fitting the software to the needs of scholars who access the manuscripts.

“It’s nice to have that sort of check as we work through the tools and see what people are doing with them,” he said. “Finding out what breaks, what doesn’t work, what people need, informs the next round of technological development.”

Students at the first meeting used the interface mainly to transcribe a phrase by identifying tiny letters from previously unstudied “marginalia” —scribes’ margin notes—in digitalized leaf from a previously unstudied copy of the Bible.

Young Xu ’17 said he felt a sense of accomplishment after completing the transcription, noting that in his Latin class most unusual abbreviations are glossed over for the reader rather than offering the chance for independent resolution. He also noted the importance of transcription from the original manuscripts.

“I think there is some essential work to be done that puts this Latin into a readable Latin that we can all work on,” he said.

Whearty emphasized the importance of exposing students to unsolved questions in medieval literature.

“I can promise you, we will discover things that no one alive knows—that’s real,” she said.

Contact Andie Waterman at andiew ‘at’ stanford ‘dot’ edu.