The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4,1968 had a ricocheting effect across the world and especially at Stanford. Although tragic, his death created an impetus for Stanford’s Black Student Union (BSU) to create change on campus.

At the convocation on campus for King’s death, BSU took the microphone from then-University Provost Richard Lyman and issued their 10 demands in response to King’s death. On that list of demands was the establishment of a black theme dorm.

For Grace Carroll ’71, the event, appropriately dubbed “Take the Mic,” was an important change from the undergraduate culture she had been experiencing at Stanford.

“What led up to ‘Take the Mic’ was the feeling of being isolated, that there weren’t many black faculty and staff members,” Carroll said. “It felt like the University sprinkled us around so that white students can have a black person in the dorm, but not understanding that African American students have specific needs that weren’t being addressed.”

In 1970, the University established its first black themed dorm in Cedro, where the percentage of black residents mirrored the University’s percentage of black students. The all-freshman dorm had an immediate impact on the class of 1974, the first class to have the option of living in black theme housing.

With William Dement, professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, as the residential fellow, the majority of the residents were assigned to the dorm as a result of their pre-med academic interests. Joy Simmons ’74 was a proud resident of Cedro and spoke fondly about her experience living in Stanford’s first black theme dorm.

“No one knew what to expect. It was all so new,” Simmons said. “For me, coming from a black high school, it was comforting and supportive to be with other Stanford students who were pre-med…we could hang together, grow together. Now when I look back, I see how magical that was.”

However, with a growing black student population, there was an increasing demand for a larger residential space for the black theme dorm. The following year, the dorm moved to Roble, where the percentage of black residents reached 30 percent.

Charles Ogletree ’75 lived in Roble for both his freshman and sophomore years as a resident and a staff member, respectively. What he appreciated most about Roble was that it provided an enriching academic, cultural and social environment for all students.

“There were evening classes taught on a voluntary basis by people like [Professor John Gibbs] St. Clair Drake,” Ogletree said. “There would be lectures from the Black Panther Party and students from the Nation of Islam. They would celebrate their religion, politics and culture in this dorm. Everything was open and available to every Stanford student and that was very important.”

Space continued to be an issue, however, and in 1974, the dorm made its final move to Olivo-Magnolia in the southwest corner of Lagunita Court. In 1976, the name of the dorm was changed to Ujamaa, which means “economic cooperation” in Swahili.

With a rich history serving as the dorm’s foundation, Ujamaa built and continues to build upon its legacy at Stanford.

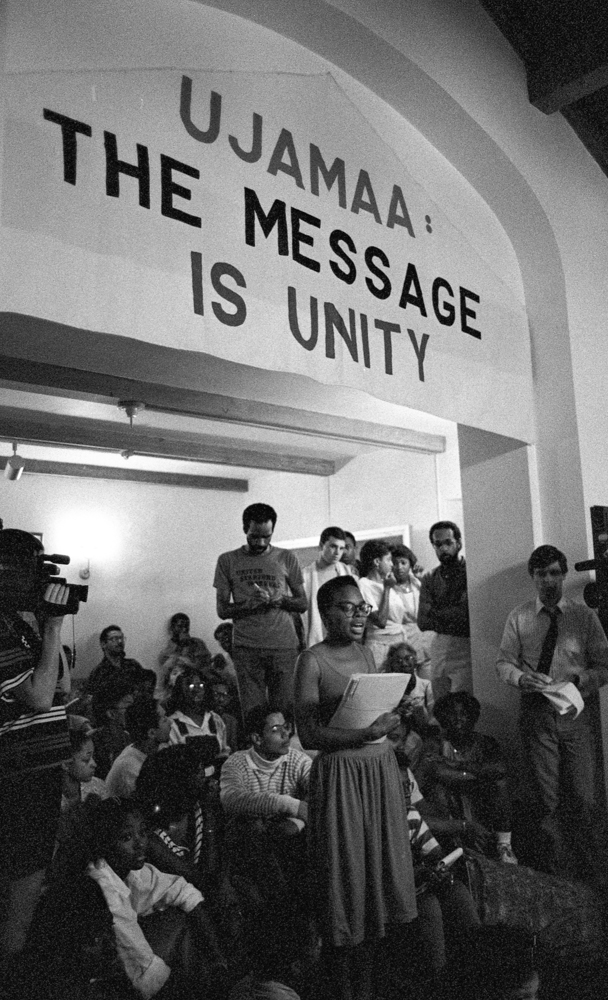

In 1988, Ujamaa provided the conversation and the initial stage upon which the University implemented its “Fundamental Standard Interpretation: Free Expression and Discriminatory Harassment” policy, more commonly known as the Grey Interpretation.

The implementation of the policy was prompted by an incident in Ujamaa, involving the posting of a black-face caricature of Beethoven on an altered Stanford Symphony flyer. This incident and a similar one occurring several weeks later in which “niggers” was scrawled across a party flyer sparked an outcry within the dorm that eventually led to a University investigation and, ultimately, to the issuance of the Grey Interpretation. The interpretation claimed that the use of racial epithets or their equivalent is a violation of the Fundamental Standard, the code of conduct for Stanford students

Even today, Ujamaa’s presence on campus is strongly felt.

With a required 50 percent of the dorm’s residents being black, Ujamaa is the only residence, and arguably the only space on campus, where black represents the majority.

Within that black majority, however, there is incredible diversity. Black residents come from across the world, represent several faiths and beliefs and are spread all along the spectrum of academic disciplines.

With such diversity among its residents, discomfort is to be expected.

“People are coming to this space never having lived in this kind of environment,” said Jan Barker-Alexander, current Residential Fellow of Ujamaa.

“It is not just students that are not black that might not be comfortable,” Barker-Alexander said. “Even the black students are uncomfortable, because many of them have not been in this situation to engage in race, class, gender and sexuality in this space. I think that discomfort is good because it helps you grow. It pushes you to learn.”

As a white resident who lived in Ujamaa for three years, Milton Achelpohl ’13 has heard the criticism that white people feel uncomfortable in Ujamaa. He thinks that the discomfort is important.

“For me as a white student, I am learning about the world through a different narrative, a different lens, which is just as important because it builds upon and challenges what I have already understood about the world and myself,” Achelpohl said.

Today, the dorm continues to host educational programs, presented by upperclassmen, every Thursday for its residents and for the broader Stanford community. With an average attendance of 65 students from both inside and outside Ujamaa, the programs engage the Stanford community in conversation about topics and issues impacting the African diaspora.

The Ujamaa community hopes that this dialogue will help ease discomfort and open up discussion to the Stanford community.

“Going to these programs and having talks with [Barker-Alexander], it quickly showed to me that Ujamaa is not just a place for African Americans,” said Bryant Johnson ’17, a resident of Ujamaa. “It is a place to spread to individuals the wonders of the African diaspora.”

Contact Chelsey Sveinsson at [email protected].

Correction: In the 14th paragraph, the article incorrectly implied that there was more than one black-face Beethoven poster. The Daily regrets this error.