A team of Stanford researchers recently found that smaller amounts of a particular protein are necessary to prevent cystic fibrosis than had been previously believed, in a research effort that also produced a new and more effective sweat test for measuring patients’ protein levels.

Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder characterized by thick, viscous secretions that affect the lungs, the pancreas, the liver or the intestine. It is one of the most widespread life-shortening genetic diseases, affecting one in 3,500 newborns in the United States.

In developing the new sweat test, the Stanford research team took advantage of a key property of sweat glands.

“It is extremely fortunate that the sweat gland has two ways of producing sweat,” noted Jeffrey Wine, professor of human biology and the team’s leader.

One of these mechanisms does not require CFTR, the protein that is defective in cystic fibrosis; the other one, meanwhile, reflects the amount of functional CFTR in a linear manner.

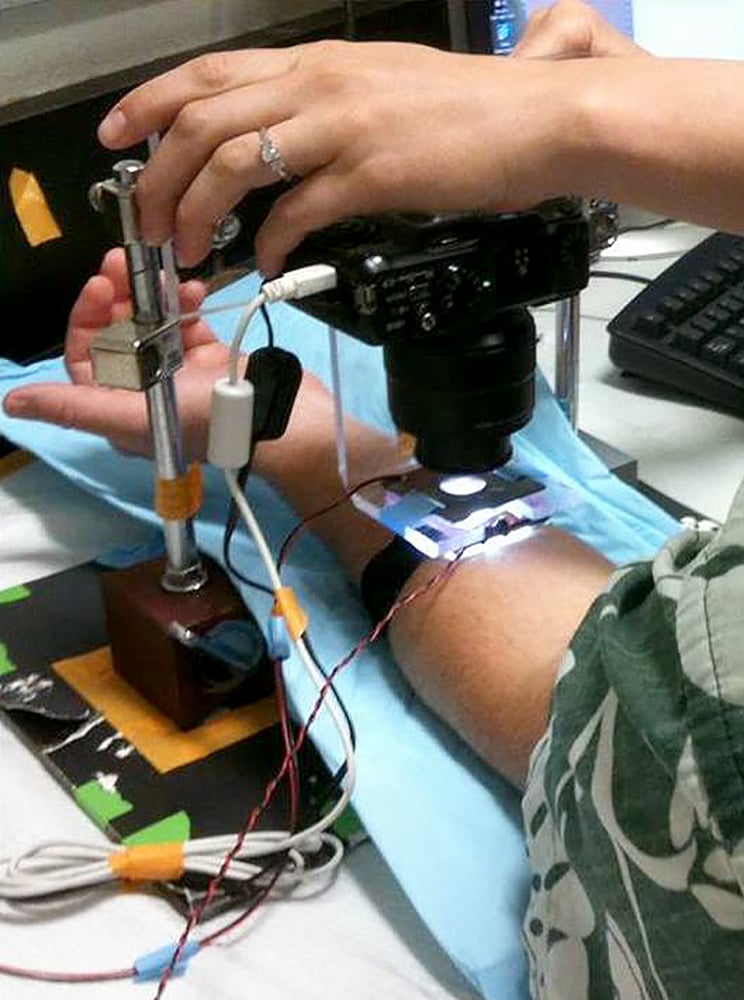

The sweat test developed by the research team is carried out using an apparatus designed by the research team. According to Jessica Char, a psychology research assistant and primary author of the study, an oil reservoir is placed on a small circular patch of skin on the subject’s arm. LED lights are placed around the circular patch of skin, illuminating the circumference of the sweat bubbles, and a digital camera placed above the circular patch of skin monitors the secretion of sweat.

Through injections of different chemicals, the researchers stimulate the glands to produce sweat or block the secretion of traditional sweat. The team was also able to develop a blue water-soluble dye that allowed them to visualize these bubbles. The ratio between the volume of CFTR-dependent and independent sweat bubbles is subsequently measured.

According to Wine, the newly developed test is more useful because it allows researchers to obtain up to 50 measures from the same patient, as opposed to classic sweat tests that measure the ratio between the total amount of sweat of two different types produced in an individual and only provide one data point per patient.

Using these new methods, the group investigated the effect of Ivacaftor, a drug used to treat cystic fibrosis in patients who have a mutation that occurs in up to five percent of cases of cystic fibrosis. They found that Ivacaftor increases the amount of functional CFTR by up to nearly 10 percent compared to the healthy control group.

Wine noted that — since big clinical trials indicate that the symptoms of patients on Ivacaftor are greatly alleviated — the team’s research offers the first suggestion that not much functional CFTR is needed to support better health.

In the future, the team plans to further improve and refine their sweat test device.

“We want to get away from all this apparatus and convert this sensor into some kind of solid state sensor,” Wine said. “We would like it to be the case that a trained nurse could slap this on a patient’s arm and analyze the data.”

Contact Silviana Ilcus at smci ‘at’ stanford ‘dot’ edu.