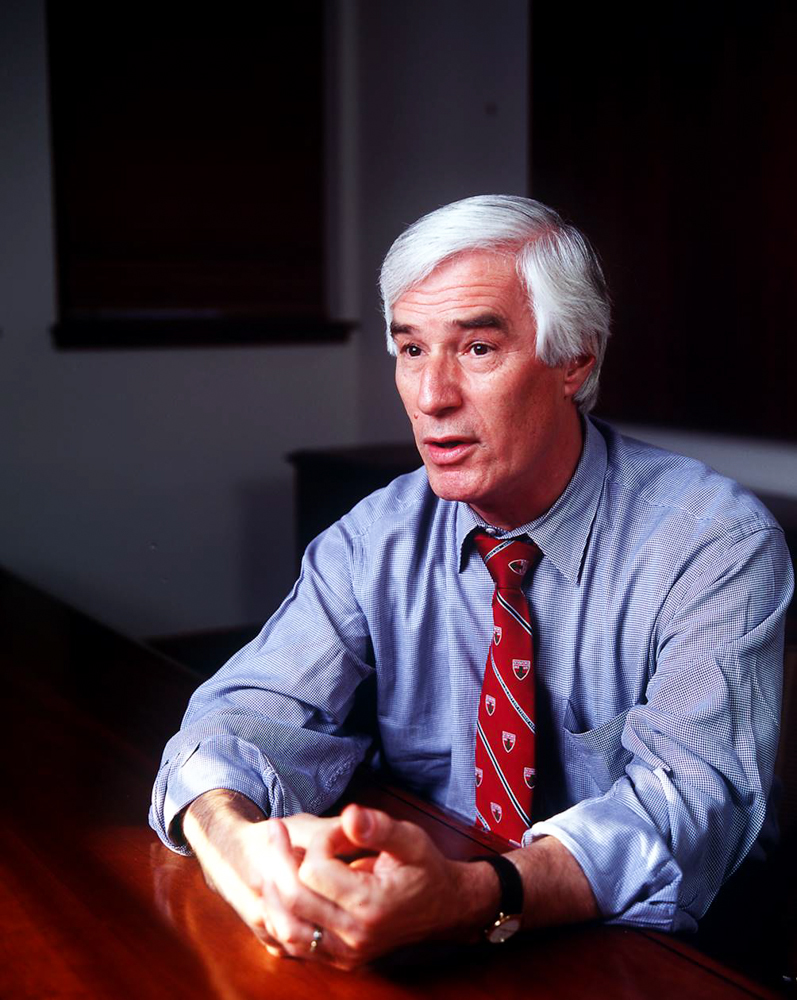

Gerhard Casper served as the ninth President of Stanford University from 1992 to 2000. Yesterday, he released a new book, “The Winds of Freedom,” that documents his time and experiences at Stanford through eight key speeches. Casper sat down with The Daily to discuss the book, his inspiration to write it and his time at Stanford.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): The year you became president, 1992, was a tumultuous time for Stanford. What do you think were the biggest issues facing Stanford then, and how was the University different then from what it is today?

Gerhard Casper (GC): Indeed. The biggest issues were on the one hand, the so-called indirect cost controversy [which is] when Stanford or any other university does research that is financed by the federal government and the university also recovers indirect cost overhead.

There was an auditor at Stanford, on campus, for the Office of Naval Research, which is our cognizant agency for indirect cost purposes. The local auditor had made allegations to his bosses back in Washington that Stanford had played loose and fast with the rules about indirect cost recovery. Now he also brought against the University a qui tam lawsuit, where the plaintiff sues on behalf of the United States government. It ended only in 1998 when the Supreme Court refused to hear the case. If we had lost that case, we’d have had an exposure of hundreds of millions of dollars.

Then there were issues that were more cultural. In 1989, the University had decided to adopt an interpretation of the Fundamental Standard, and it outlawed discriminatory harassment, fighting words, face to face [harassment], for racial and other reasons. It was, in a way, a fairly limited rule, but the politics of that time were very different because many people criticized the University for curtailing speech.

Finally, perhaps, another big issue that had gotten a lot of attention in the national media, and a lot of attention from Stanford alumni, was the [changes in the] humanities requirement in the [freshman] year.

TSD: What was the environment on campus like then compared to today?

GC: That’s an interesting question, and I often ask myself that. The early ’90s were really marked on campuses by what I might call identity politics and multiculturalism. There were various controversies where minorities insisted recognition by the universities qua their own identity, and there were some disputes, especially with Chicano students, in 1994. There was a sit-in the Main Quad, and a hunger strike. These matters more generally, of multiculturalism, were where the issues was not diversity as such, but whether beyond that the University should recognize separate aspects of various cultures represented.

TSD: When you talk about these issues, were there certain policy changes adopted by the University in response?

GC: Yes, though if you take a look at my book, you will see that it is not so much rules or policies, but my efforts to set a different tone. There were certain points on which I was very clear, though. For instance, the Chicano hunger strike, which attracted support from several hundred students at the time, they made certain demands. We looked at certain issues, but I rejected out of hand what was called the politics of ultimatum—it was very clear that at least as long as I was president, I would not make concessions under pressure.

We also toughened academic requirements at the time—we introduced the failing grade. Another major change that came, and that I worked on very much, did not involve a rule change, but rather we created the freshman and sophomore seminars, where every freshman and sophomore has the opportunity to take a seminar with a faculty member limited to 14 students, and that to me was very important for the intellectual environment.

TSD:What inspired you write a book now? What was the process like?

GC: In some ways, it was very peculiar. Shortly after I stepped down as president, I thought it would be interesting to take my major speeches and those dealing with academic freedom and talk about what I really thought and believed in, what motivated me to make these speeches and what the context was.

Each chapter at first has the text of the speech—I didn’t include all of my speeches in the book, since I made over a thousand speeches in eight years. Each chapter has the text of the speech, and then I explain the content that it was made in and discuss the subtext. Sometimes I have also added a postscript with related matters, and I found this format gave me a lot of space to add other issues and creativity that I might have not linked to the original speech.

Contact Nitish Kulkarni at nitishk2 ‘at’ stanford ‘dot’ edu.