Four of California’s top research universities, including Stanford, have joined forces in an effort to increase the presence of underrepresented minorities among faculty in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The California Alliance for Graduate Education and the Professoriate–a collaboration between Stanford, UC-Berkeley, UCLA and Caltech–will directly feature input from the School of Earth Sciences, the School of Engineering and some departments within the School of Humanities and Sciences.

“The idea is for the four institutions to work together to hopefully achieve something that each of us can’t get our arms around on an individual basis,” said Jerry Harris, associate dean for multicultural affairs and professor of geophysics at the School of Earth Sciences.

The history of the consortium

The collaboration was first proposed in 2010 by Mark Richards, executive dean of the College of Letters and Science at Berkeley, in an effort to boost the faculty presence of underrepresented groups–including African Americans, Hispanic Americans, American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders–to a level commensurate with national demographics. Currently, according to Harris, the “pipeline”–the process that begins with Ph.D. programs and ends with professorship–experiences less diversity at each step.

Richards initially reached out to Stanford seeking collaboration. After three years of collaboration, the National Science Foundation awarded the alliance $2.2 million last September.

The grant, which will last until February 2017, provides an opportunity for the participating universities to share successful practices in recruiting and retaining underrepresented minority groups. It will also allow graduate students, post doctorates and faculty members at the four institutions to network more regularly.

“A diverse group of smart people will trump a less diverse group of smart people,” Harris said. “Sometimes, people who are trained differently will take a different approach to a complicated problem. The interaction of these people together will lead to a better solution.”

Minority representation at Stanford

Tenea Nelson, assistant dean in the Office of Multicultural Affairs at the School of Earth Sciences, is a member of the consortium’s implementation team. She said that she envisions the alliance yielding increased mentorship programs, scientific discussions and more research collaboration among the four institutions, and expressed hope that the efforts will create a more supportive professional community for underrepresented minorities.

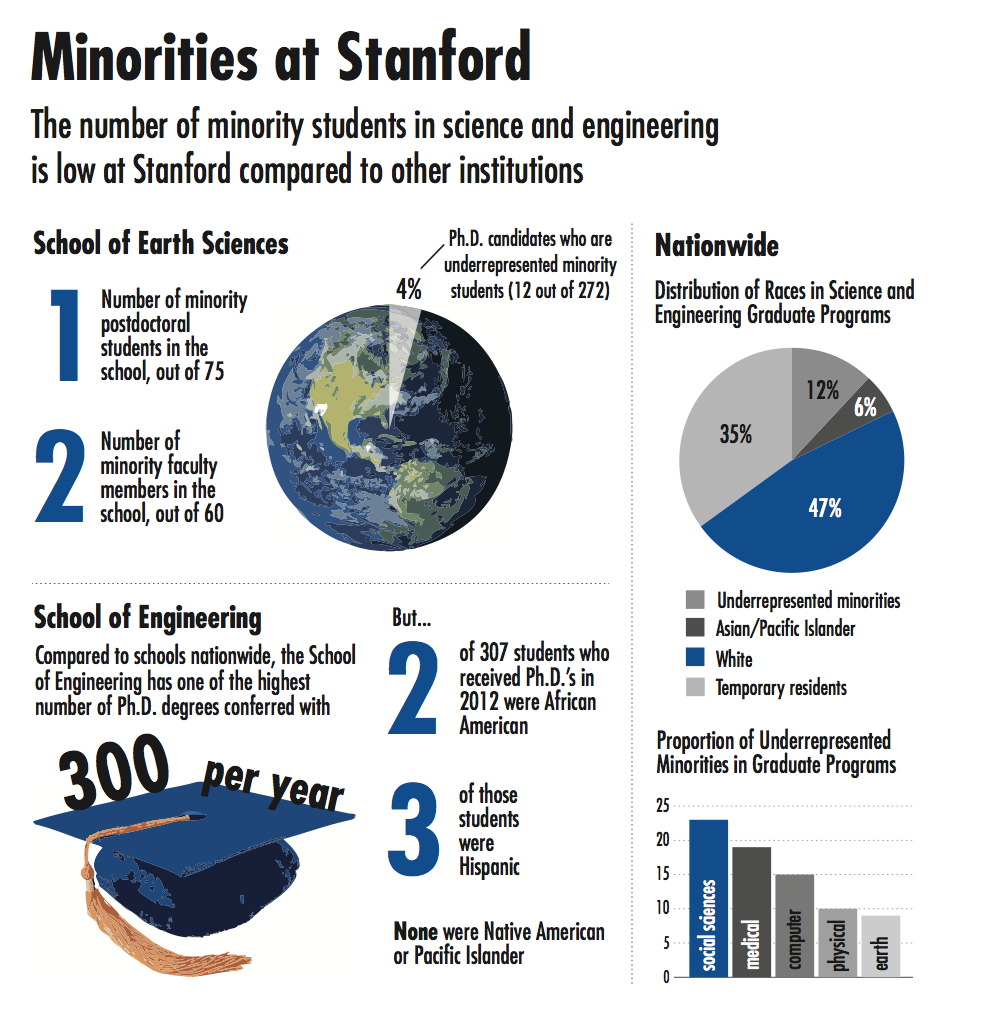

Currently, participation by underrepresented minorities in the “pipeline” at Stanford remains low. According to Nelson, in the School of Earth Sciences, 12 of the 272 Ph.D. candidates are underrepresented minority students. There is one minority student among the 75 post-doctorates and two minority faculty members out of a total of 60.

The School of Engineering faces the same problem, according to Noe Lozano, associate dean for engineering diversity programs and another member of the consortium’s implementation team.

According to Lozano, the School of Engineering confers an unusually high number of Ph.D. degrees each year–an average of 300 degrees, compared to other schools that award anywhere between 10 and 50.

There remains, however, a clear imbalance in the distribution of underrepresented minority students. In 2012, of the 307 students who received Ph.D.’s in the School of Engineering, only two were African American and three were Hispanic. None were Native American or Pacific Islander.

“We look like the nation at the undergraduate level, but at the Ph.D. level we’re nowhere near where we should be,” Lozano said. “It’s totally bimodular–two different worlds.”

Part of the problem, according to Lozano, is a diminishing “talent pool” of domestic students from which the School of Engineering is able to draw, forcing the School to accept more international students into its Ph.D. programs.

“If we didn’t have that [international component], we would have bigger problems,” Lozano said.

Although competition in academia is extensive for all students, regardless of race or ethnicity, it especially deters underrepresented minorities from considering professorship as a viable career option, according to Jeremy Brown, a fifth-year Ph.D. student and one of the few minority students in the geophysics department at the School of Earth Sciences.

“There are not so many jobs there, and the jobs that you might want at like Harvard or Stanford are very competitive,” he said. “Being a minority, you might feel like you’re not coming in at the same level as other candidates.”

Brown, who plans to work at a private company in the energy or gas industry after obtaining his degree, framed the path to professorship is a long and stressful one and explained that the alliance’s goal “to have people there that are also going through that [who] are minorities is a big deal.”

“If I had that community, I think it definitely would have made a big difference for me too,” he added.

Contact Vanessa Ochavillo at vochavillo ‘at’ stanford ‘dot’ edu.