The phrase “Silicon Valley” conjures up images of Facebook and Google and technology startups. But within the culture of programmers and bankers and venture capitalists lies a less publicized group: food entrepreneurs.

Stanford’s Food and Agribusiness Club hosted “Food Entrepreneurship 101: The Real Deal on Starting a Food Business” at the Graduate School of Business (GSB) this past Tuesday. The panel included founders Marc Manara (Kincao), Ching-Yee Hu (Sprogs Fresh), and Matt Gosselin (Pure Provisions). Austin Kiessig, a GSB graduate and former president of the Food and Agriculture Club, moderated the discussion.

Who they are

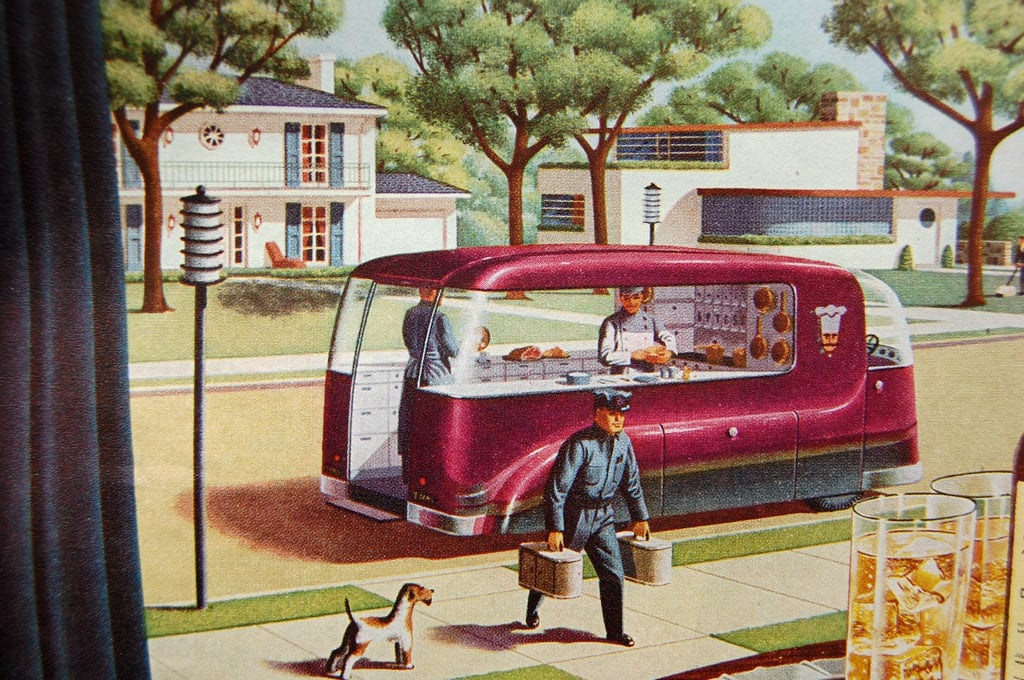

Kincao, which originated in Stanford’s LaunchPad class at the Institute of Design (d.school) and launched last year, aims to help its customers eat healthier by delivering nutritional and sustainable meals directly to their doorsteps. Sprogs Fresh’s first product is Rice Scooters, hand-held brown rice balls meant to feed “Healthy Foodies on the move.” Pure Provisions focuses on creating healthy, gourmet jerky.

While Manara has been working on Kincao since graduating from the GSB in 2013, Hu spent 10 years in the food industry before trying to start her own food company a year-and-a-half ago. Hu said her most recent adventure with Sprogs began around six or seven months ago when she realized that “the traditional food industry is broken.” Gosselin’s work in the food industry began on Wall Street at an investment bank and he drew on his experience with industry trends and investment to start Pure Provisions more than two years ago.

What customers don’t realize

Despite their diverse backgrounds, all three entrepreneurs offered similar insights about the food startup world, and moderator Austin Kiessig, who spent two years in the food industry and at venture-backed startups before working on a startup food venture of his own, also contributed to the discussion.

“There’s a visceral resonance of building a food business,” Kiessig said. “But it’s slower growth, it’s harder; it’s more of a slog. It’s more competitive than a lot of the tech entrepreneurship you see.”

Unlike technology companies, a few hours of coding cannot get a food startup running overnight.

“Even when I had budgets in the millions of dollars, there are a lot of physical realities that you don’t think of when you’re launching a startup software company,” Hu said.

Millions of dollars will be invested in packaging and flavor alone and as a result, small adjustments have huge costs. Buyers often do not realize the time, energy and money necessary to add a flavor or change a label.

“It might take three weeks to print the dye plate before you print the actual film and then you have to change the equipment to change the size of your bag,” Hu explained.

“There’s also an element related to safety that I think I really underestimated before I got into the industry,” Hu added. “You can kill someone. You can make someone incredibly sick. You can cause a woman to have a miscarriage. These are things that you have to take very seriously and be very cognizant of, and there are a lot of regulations and precautions that you have to take for that that slow you down.”

Hu also spoke about the transition from working in the larger food industry to starting with nearly nothing as a small company.

“It’s not glamorous stuff,” said Hu. “My friends are still senior executives at large companies flying in jets to do market research in Switzerland or tasting new flavors in Tokyo, and I am trying to figure out how to find a sticker that won’t stick to the bag so that you can open it.”

Gosselin spoke about another aspect that customers often fail to understand: the margin extracted from the product from when it leaves the manufacturing facility to when the customer purchases it. While the company usually has a margin of about 40 to 50 percent in order to cover the marketing costs of brand growth and product development, distributors may take an additional 20 to 25 percent. After distribution, retailers may take another 30 to 55 percent, Gosselin explained.

“If you can imagine that I can manufacture one of those bags for a dollar, the consumer is probably going to pay $5.50 or $6 for it,” Gosselin said. “By the time it gets to you, so much value has been extracted, and nothing’s changed about the product.”

He and the other panelists believe that the process of getting the products to market is an area ripe for entrepreneurship. Hu emphasized that this is especially true of fresh food. These are exactly the reasons why bad-for-you products end up on grocery store shelves. In comparison to the costs of organic, high-quality food, using processed and unhealthy additives helps bring the price down for big manufacturers.

Why they love what they do

Yet despite the financial and logistical hurdles of starting a food company, all three founders have not forgotten why they first entered the food industry.

Both Gosselin and Manara found the tangible results of their work rewarding. Manera explained that he enjoyed “being intimately involved in a product” while rapidly prototyping and working face-to-face with customers to improve their work.

“I love food, and this is a passion. That’s why I got into this in the first place,” Manera said. “We have a mission that fuels what we do every day … It’s fun to get up in the morning and go do what we do.”

Hu found the small scale “thrilling” and said that watching customers pick up her Scooters at her local grocery store was “the most exciting thing to happen in my day.” She also contrasted her current work with her previous experience in the large-scale food industry.

“It’s very refreshing because I’d gotten to the point in my previous year where I felt like I spent a lot of time generating Powerpoint propaganda,” Hu said. “Now the numbers are humiliatingly modest. I am on year two of no salary. I feel like a charity case sometimes … but there’s not a moment of my day that feels like BS.”

Kiessig summed up his love for the industry in one sentence: “I think food is the intersection of everything that matters.” Energy, the environment, public health, and even labor are all involved in the production, manufacturing, and consumption of food.

“Speaking from a personal standpoint, I think food is a good place for generalists who can do a bunch of things at once,” Kiessig said. “I didn’t have any really valuable skills … I don’t code. I don’t build things like an engineer would. But I can see the big picture and drive towards a goal.”

After all, food plays a necessary role in our everyday lives.

Hu joked, “No one’s going to stop eating.”

See part two here.

This post was originally published on thedishdaily.com before it was acquired by The Stanford Daily in summer 2014.