Stanford is a defining example of how the issues most important to us nobody really understands. Take the most famous example, the so-called Stanford bubble, a term so ubiquitous that the Admissions Office is now using it in its recruiting strategies. What is the Stanford bubble? Like the term syndrome in medical parlance, the term “Stanford bubble,” along with “duck syndrome” and “techie-fuzzy” is something that we say to describe phenomena that nobody really understands. Put together, these three concepts can be used to describe any kind of dissatisfaction we might have with a campus that ultimately makes it distasteful to have distaste for any aspect of it.

Why can’t we be unhappy about Stanford? There are two ways to approach it, one fundamentally repressive and the other fundamentally accepting. I said earlier that plenty of Stanford applicants deserve to enter the University, while only a few of them actually will. That is true. But the full truth is that while plenty of applicants deserve to enter Stanford University as it actually is, nobody deserves to be here as we imagine it.

If you’re taking that as a negative towards Stanford, you’d be wrong. Stanford is a great place. Yet I ask everyone here — what did you envision Stanford as being when you first stepped on this campus? I assume that your view is different now.

To generalize, the popular conception of Stanford seems to be the place where everything is perfect. The great universities of the East Coast are generally cast as institutions that are imperfect but that nevertheless have a certain weighty dignity to them. Stanford markets itself as a place that has no drawbacks — one that can actually be all things to all people.

What’s the point of selling Stanford’s resources? It allows Stanford to sell ourselves to ourselves. Naturally, people dream of Stanford in the ways that suits them most — the way that allows them to imagine their own dreams being realized, the way that ultimately allows them to feel best about themselves. Before we become students here the University is a blank slate, and we almost always see fit to make it our blank slate. Stanford, we imagine, will give us the tools to accomplish all our dreams, to do everything we could have ever imagined and then some. In doing so, it will, in short, make us perfect, and confirm our own hidden hopes of perfection. I admit that I was one of these people. It happens. It’s quite unavoidable.

But I can’t help but feel a little squeamish when the University tries to confirm these dreams after we arrive, even though they cannot all be true. It wasn’t long ago that I was sitting in Memorial Auditorium for New Student Orientation and the keynote speaker confidently declared, “Stanford validates who you already are.”

If there’s anything that the University should do, it should be to directly deny that thesis. We aren’t perfect, and our perfection then can’t confirm the University’s perfection. We can become better because of the resources that Stanford provides us, for sure. There are plenty of foibles we ourselves would acknowledge that we hope that college will eradicate. But what often goes unnoticed is that there are also always things fundamental to ourselves and our own aspirations that are flawed and that must change. It is inherently selfish to think that Stanford can only be wonderful if it conforms to your own sense of who you are and what Stanford should be.

What, then? We blame the limitations of Stanford. We place our problems on the Stanford bubble. The thesis of our notorious bubble is that our opportunities are not limitless, as we had dreamed, but ultimately circumscribed by our isolation. Similarly, the so-called techie-fuzzy divide supposedly describes our own internal circles of distrust, where the culture of the University forces us to be either one or the other — thus blaming our issues on society limiting our options and desires, when in reality we are mostly free to study as we choose.

The infamous duck syndrome, then, is a quintessentially passive-aggressive mode of complaining about these two fundamental complaints, and it’s not healthy. It’s not healthy because it allows the wounds caused by the fall of our aspirations to fester. But because it also involves that stiff-lipped silence on the outside, it also allows us to dodge the fact that our aspirations say everything about ourselves. If our aspirations fail when every opportunity is available to us, as we know is false and yet still fear might be true, then something is wrong with us. And everybody is scared about being wrong.

We are in denial and in full blame-society mode at the same time.

***

People say that in paradoxes such as this, you should take a stance. Not all stances are good, however, and in particular, being okay with being wrong is not the answer.

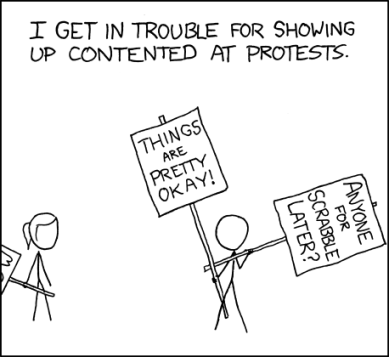

It is okay to be disappointed. It is okay to realize that the University is not and could never have been the sum total of our wildest hopes and dreams. Stanford is a great place even if it isn’t perfect, and there are plenty of wonderful people here who are wonderful even if they aren’t perfect themselves. I think Stanford is awesome. Most people here would agree, and I suppose that’s why although the student body is pretty liberal, the mood of the campus is fundamentally conservative. Regardless if a student has disavowed duck syndrome or is fully invested in it, his/her motto is probably that of the xkcd cartoon pictured here: “Things are pretty okay.” We’re cool with what we have. With a few exceptions, such as (possibly — I haven’t asked him) the columnist who shares the Monday opinions page with me today, Stanford students are pretty happy with the way things are.

We can be happy here even if we aren’t perfect. But though we have to recognize this truth in order to understand the University for what it is, such a truth cannot be our final goal. That sentiment veers towards the complacency of indifference. And indifference is a far more insidious redefinition of who we are and what we seek to be. It is not a cause for celebration when D.J.R. Bruckner writes of a “new cynicism” in The Los Angeles Times. “What you hear and see is not rage, but injury, a withering of expectations,” Bruckner pointed out. He wasn’t happy. Nor should we be.

Our degrees are nice to have, and the University’s imprimatur opens doors. We can’t disagree on that point. But if we are complacent, it would be far better for the University to give our spots to people who actually want to do something meaningful with the opportunities we have been given. Stanford’s imperfections are only acceptable because they teach us that we have to redefine our aspirations — that we now have to seek out the new new horizon. It is only okay to realize that we are not perfect ourselves as long as we acknowledge that perfection is still a goal worthy of our efforts, hopes and dreams.

***

One last musing on indifference.

I write this on Easter Sunday, a day when Christians commemorate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. Christianity teaches that Jesus chooses people to join Him in that resurrection if they only place their faith in Him and His calling. Protestants believe in salvation by faith alone; Catholics delay the process a bit with the doctrines of purgatory and good works, but at least to my theologically untrained eyes, despite differences in principle, it seems like both paths eventually arrive at the same point.

Salvation through faith is a beautiful belief. It preaches not just redemption but universal redemption, and indeed the pastor who is raised in the faith from birth is every bit the same as the thief who embraces the faith in his last moments, dying in agony, impaled on the cross in one life and saved in the next.

Yet the fundamental lesson of Christianity is that surety in salvation is not enough. Even if we believe that resurrection is certain, we cannot simply settle for that. To believe that God loves us despite our shortcomings is faith; to believe that God’s love makes our shortcomings okay does a great injustice to that love. For if we loved Christ we would want to become better, if only for Christ’s sake.

What Christianity teaches us is that despite having every reason to be complacent, we absolutely shouldn’t.

Happy Easter.

Winston Shi would like to make it clear that he would rather play Cards Against Humanity than Scrabble, for what it’s worth. Contact him at wshi94 “at” stanford.edu.