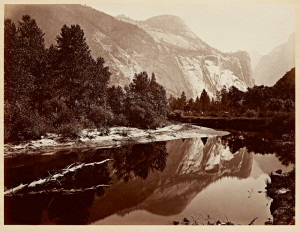

The 20th-century landscape photographs of the American West by Ansel Adams and Edward Weston may now be so familiar that we take them for granted, but almost a century before them, there was Carleton Watkins, whose grand vision of the West helped shape theirs.

“Carleton Watkins: The Stanford Albums,” currently on view at the Cantor Arts Center, features 85 vintage prints, beautifully framed and installed, and in superb condition. They have been kept unbound in oversized albums by their owners, and subsequently archived in Stanford University Library’s Special Collections Department—until now.

A native New Yorker who came to San Francisco in 1851 in pursuit of gold, the young Watkins found his calling in photography—a new medium at the time, born about the same time as the ‘photographicist,’ to use the artist/businessman’s term – by accident. Watkins would mine images rather than gold dust, producing, over 50-odd years, almost 10,000 photographs—reproduced in stereo cards and books of mammoth 18-by-22-inch plates—of the developing West. These iconic images, combining stunning topographic details and panoramic sweep, dazzled the world, winning Watkins international acclaim and, for a time, financial success.

The landscape painters Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Hill and William Keith knew Watkins and his work; the transcendentalist philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson declared that Watkins’ photos had proved giant sequoias no myth. The New York Times praised the images as “indescribably unique and beautiful.” The impact was not confined to artists and writers, however. Watkins’ 1861 photos of Yosemite were instrumental in aiding the passage of the 1864 Yosemite Grant Act exactly 150 years ago, preserving spectacular wilderness from development and setting a precedent for the later national parks system.

Where Adams and Weston present lyrical, even Romantic views of pristine nature, Watkins seems more realistic and modern. His photographs, commissioned by mining, ranching, manufacturing and railroad interests, were in fact admitted as documentary evidence in court cases, reportage without editorializing, despite their sterling aesthetic qualities.

The Cantor exhibition features 85 of the 156 prints that Watkins made in three albums for collector Mary “Mollie” Latham, wife of the banker who defeated Leland Stanford in California’s 1860 gubernatorial race. She later sold them to railroad magnate Mark Hopkins, whose son later bequeathed them to Stanford. Photos of her magnificent mansion help viewers imagine how Gilded Age aristocrats might have viewed “Photographs of the Yosemite Valley” (1861 and 1865-6), “Photographs of the Pacific Coast” (1872-6), and “Photographs of the Columbia River and Oregon” (1871).

The photographs are grouped by location, as Watkins presented them. Different works will resonate with different viewers, but the incredible detail captured in these large, 18-by-22-inch photos will impress even art mavens used to huge digital blowups.

We should also remember the heroic efforts needed in the mid-19th century to capture these images. The cumbersome wet-plate collodion technique required photo paper prepared with silver salts and egg-white albumen and heavy glass plates that were treated in the field with acids, ether, alcohol and silver nitrate. Watkins hauled 2,000 pounds of equipment, including his darkroom tent and custom-built “Mammoth Camera,” up treacherous mountain passes in horse- and mule-drawn carts in search of “the perfect spot.”

His early success, unfortunately, did not last. Plagued by bankruptcy and blindness, Watkins was committed to the Napa State Hospital for the Insane in 1910. He died there in 1916, and was buried in an unmarked grave. Stanford University would have acquired the photographer’s entire archive in 1906 had Watkins’ studio not been destroyed, just days before a planned curatorial visit, by the San Francisco earthquake. A century and a half later, Watkins’ images look both timely and timeless, The exhibition features digital enhancements from various Stanford departments and disciplines that are informative without being distracting. A lavishly illustrated (and bargain-priced) catalogue from Stanford University Press will be available shortly.

Contact Dewitt Cheng at dewittc “at” stanford.edu.