(Courtesy of Steve Castillo/USA Today)

Stanford researchers have taken a big step in developing a pure lithium battery. The new battery, which may not reach the market for three to five years, would allow an electric car to have a 300-mile range and would triple the time a cell phone’s battery would last before needing to be recharged.

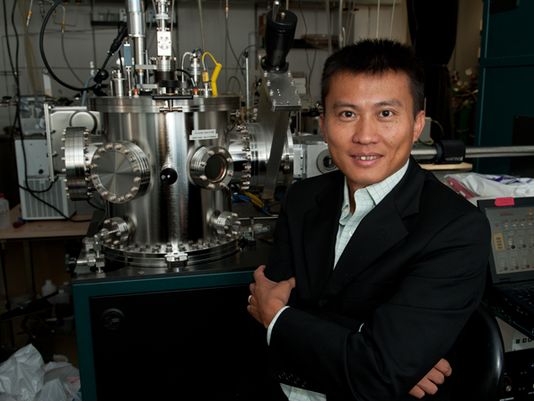

The team of researchers working on the battery included Steven Chu, former Secretary of Energy and professor of physics and molecular and cellular physiology, and Yi Cui, associate professor of material sciences and engineering.

In a breakthrough, the researchers said in a paper published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology that they have found a promising strategy to accomplish what battery designers have been trying to do for decades: design a pure lithium anode.

Cui, leader of the research team, said in a Stanford announcement that lithium has the greatest potential.

“It is very lightweight, and it has the highest energy density,” Cui said. “You get more power per volume and weight, leading to lighter, smaller batteries with more power.”

Chu, who is also a Nobel laureate in physics, recently resumed his professorship at Stanford after leaving the Obama administration.

“If we can triple the energy density and simultaneously decrease the costs four-fold, that would be very exciting,” Chu told the Stanford News Service.

Guangyuan Zheng, the first author of the paper and a doctoral candidate in Cui’s lab, said that engineers had given up trying to overcome the challenges of using lithium in anodes. The recent battery fires in Tesla cars and on Boeing 787 Dreamliner jets are examples of the challenges of lithium ion batteries.

“[We] found a way to protect the lithium from the problems that have plagued it for so long,” Zheng said.

In the paper, the authors explained that they are overcoming the problems posed by lithium – namely overheating, chemical reactions and buildup – by building a protective layer of interconnected carbon domes on top of their lithium anode.

The team called this protective layer “the nanosphere,” and it resembles the shape of a honeycomb. This new layer creates a flexible, uniform and non-reactive film that protects the unstable lithium from the drawbacks that have made using it such a challenge.

In addition to co-authoring the paper published in Nature Nanotechnology, Cui heads a team of scientists from the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory (SLAC), which is making and testing new types of lithium-ion batteries.

According to a recent announcement in a SLAC news release, Cui said that his lab is also working on making another possibility for a better battery: a sulfur cathode to replace today’s lithium-cobalt oxide.

Contact Jacqueline Carr at jacquelineecarr ‘at’ gmail ‘dot’ com.