Stanford lost to Utah. They are now 5-5 and below .500 in conference. Against Utah, they couldn’t move the ball in regulation, and they gave up twice as many scores in overtime as they did in the previous 60 minutes. In a game where touchdowns were at a premium, Utah defensive lineman Nate Orchard’s sack of Kevin Hogan to open the second overtime essentially doomed the Cardinal to a field goal; Utah scored a touchdown on the next possession, turning Orchard’s sack into a game-winning play on defense,

Some people may question why the Utah record holder for single-season sacks was left completely unblocked on one of the most important plays of the game. However, looking at the film of the game, Orchard going unblocked was the entire point. Here’s why.

***

People don’t normally criticize the idea of option football; Stanford runs it, Oregon shredded Stanford with it. And the basic structure of the option is that a player goes unblocked. in other words, purposefully leaving a player unblocked is a settled and accepted part of offensive football. This play, while not an option play, follows that principle.

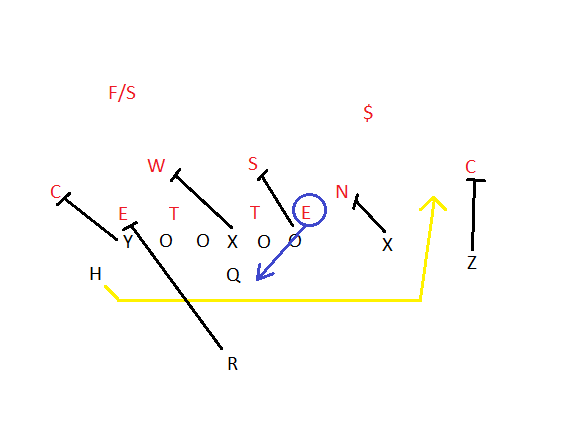

Stanford ran one of my favorite concepts in football. It’s a zone slice fake with the wing leaking backside. Translating football to English, this means that the offensive line and tight end fake a zone running play to the left. The H-back (typically a tight end, but in this case running back Christian McCaffrey), comes across the formation, ostensibly to block the backside defender on the defensive line (Orchard, circled in blue) – a very popular blocking strategy across all levels of football. Meanwhile, Remound Wright (R) heads to the left to sell the zone fake, and McCaffrey actually sneaks beyond the formation and to the flat, where Hogan will pitch him the ball.

It’s not like Orchard was going to cover McCaffrey, so on paper, not blocking Orchard simply frees up an offensive linemen to block somebody else. In this case, right tackle Kyle Murphy headed upfield and sealed the Utah linebackers away from the play, something he wouldn’t have been able to do if he was blocking Orchard. These linebackers were the main threats to McCaffrey on the backside.

The play worked as designed, in that McCaffrey found himself on the right side of the field with nobody within 10 yards of him. If Hogan had gotten the ball out in time, Stanford probably would have gotten a critical first down. Unfortunately, Orchard rushed into the backfield, and with the quarterback lined up under center and looking backwards to sell the fake to Wright, Hogan didn’t see Orchard coming until it was too late.

Was this necessarily the right play to call? I am obviously biased in favor of yes, despite the final outcome. And while it would have been difficult for Hogan to get the play off, I still contend that it was possible. (Online readers, see for yourselves.) Maybe the play would have been more sound from shotgun, but I’ll admit that I’m not getting paid six or seven figures to coach football, and so I’ll defer to the coaches on this one.

***

As we approach the end of the season, I just want to talk about how I choose my plays for this column.

I get that the play I chose was not necessarily the most important one in the game. After all, while Orchard made it incredibly difficult for Stanford to score a touchdown on that drive, the Cardinal didn’t know that they would need a touchdown to keep the game alive. Orchard’s sack yardage pushed Jordan Williamson’s field goal spot to over 50 yards out, and no kicker will reliably score from that distance – indeed, late in the fourth quarter, David Shaw punted on fourth and long instead of kicking a 51-yarder – but with no other feasible option but to kick, Williamson’s desperation field goal in overtime at least got points on the board. So this play didn’t immediately end the game.

In fact, most of my readers will probably ask about two other plays: Travis Wilson’s touchdown pass to Kaelin Clay to open overtime, and the game-winning toss to Kenneth Scott. But they’re not really that interesting to break down, because they’re primarily matters of execution and not of scheme.

The Clay touchdown was a botched coverage on a common smash pattern; Clay beat the guy in front of him, a player who had essentially no safety help, on a corner route to the sideline. Jordan Richards was playing 25 yards deep in the middle of the field, but he couldn’t catch Clay, who was 20 yards away from him; no college player should be expected to do that.

The Scott touchdown involved Scott isolated on the far right on an island, one-on-one, against Alex Carter. Carter had no safety help; Scott lined up too far away from the strength of the Utah formation for Stanford to justify that. As I watched the play in real time, Carter expected a slant, as he should have, and lined up with inside leverage to stop the in-breaking route. Scott probably fooled Carter with a double move, faking a corner fade before breaking on the slant, which caused Carter to lose his inside leverage. A second later, Wilson found Scott wide open in the end zone. Hate to see a guy lose a battle one-on-one, but sometimes that happens. Stanford held Utah to 7 points in regulation, and let’s remember that the Cardinal don’t even get to overtime at all without Carter. Onwards to Cal.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.