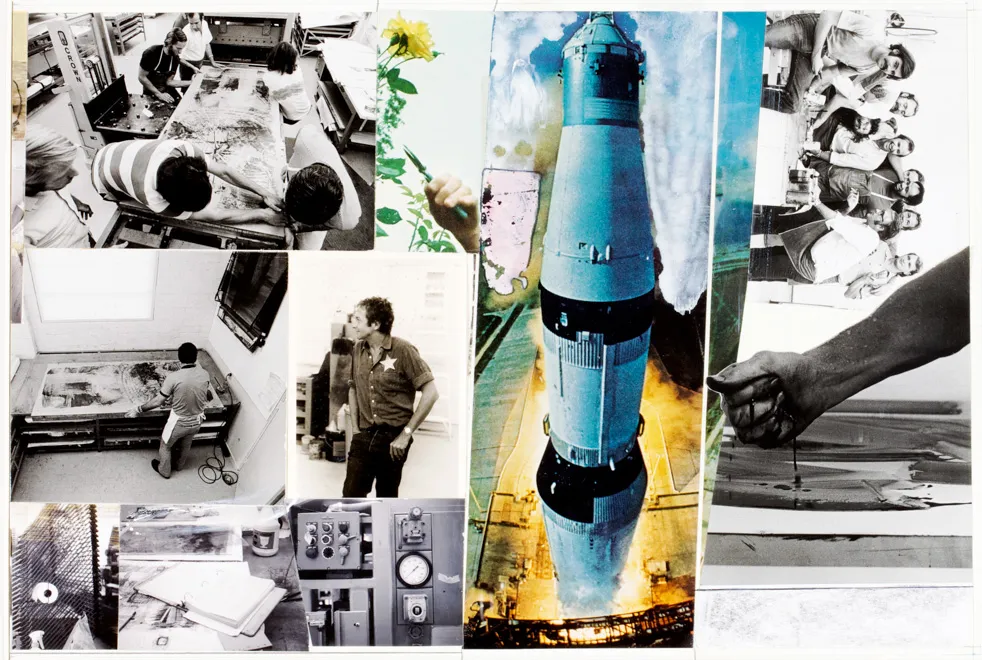

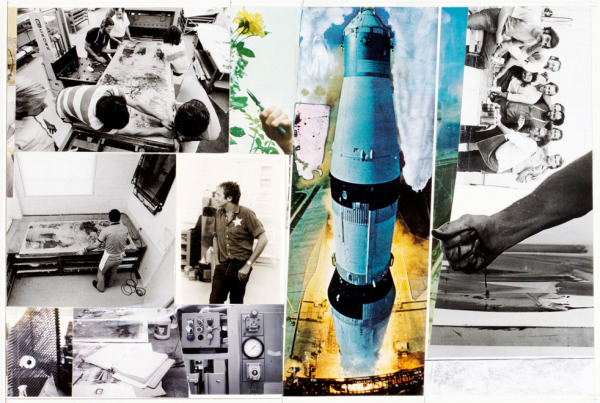

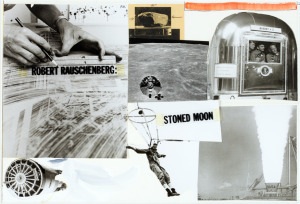

As part of a campus-wide initiative called Imagining the Universe, “Loose in Some Real Tropics” delves into the relationship between visual arts and cosmology. The Cantor Arts Center exhibit showcases American pop artist Robert Rauschenberg’s “Stoned Moon” projects, a series of lithographic prints, collages, photographs and drawings that documented the aeronautic milestones achieved by NASA during the Apollo era.

James Merle Thomas, guest curator for the exhibit, sat down with The Stanford Daily to answer some questions explaining his interest in the Rauschenberg exhibit and the aesthetics of the Apollo era.

The Stanford Daily (TSD): What sparked your interest in Rauschenberg’s work, and what inspired you to take on this project of curating the exhibition?

James Merle Thomas (JMT): I actually graduated from Stanford; I completed my Ph.D. in the art history department about a year ago, and my research, when I was at Stanford, was about exploring the relationship between artists in the 1960s and NASA. More generally speaking, I was interested in the connection between art and science in the 1960s. This project evolved organically from my ongoing interest in that time period.

TSD: Why are you drawn to the aesthetics of NASA and the Apollo era, and why is it important that we understand its significance?

JMT: There are two parts to this question. The first is that most people don’t actually remember NASA and the Apollo era firsthand. We experience it only through pictures and films. Rauschenberg’s interpretation of those events does the very important job of showing us a very different kind of narrative. It’s less about heroic astronauts planting flags; it’s more about understanding the look and feel of the whole era. Rauschenberg’s project raises questions about the role that a large federal agency like NASA should play in government and the roles that art and science should play in relation to one another.

TSD: How does the Rauschenberg exhibit relate to some of the other projects you’ve worked on?

JMT: I’m broadly interested in projects that bring together art, politics and technology in some combination. For example, many of my dissertations involved artists like Robert Irwin and James Turrell as they interacted with psychologists who were employed by NASA. There’s a sort of historical part to that. At the same time, I’ve worked for almost a decade now in the field of contemporary art and have organized large exhibitions of contemporary art from all over the world, ranging from African photography to Chinese video art to sculpture by European avant-garde artists. In this case, I wanted to very thoroughly research a project that has not really been understood and bring together all of the different parts (lithographs, collage work, transfer drawings and photographs) into a show.

TSD: Why is it important to note the relationship between visual arts and the sciences, especially cosmology?

JMT: When you start looking closely at the images that NASA produces of the universe, you realize that it’s never a straightforward photograph. At some point, someone needed to make decisions about [the] contrast used and the colors that were assigned to the data, so that we could visualize something. This is a very contemporary way of thinking about aesthetics and art and the way we look at the universe. That’s actually very similar to what Rauschenberg was doing with his work in the 1960s, and it’s similar to the way that maybe someone would make a landscape painting in the 19th century — for example, we can understand the American West through a landscape painting of Yosemite. In that way, I’m really interested in understanding Rauschenberg’s work as a historical narrative.

TSD: What are some other creative endeavors you plan to work on? Do you have any future plans for projects at the Cantor Arts Center?

JMT: Cantor’s been a wonderful partner, and I’ve welcomed the opportunity to work with them in the past. I have a very good relationship with the Cantor [Arts Center at Stanford University]. I’ve organized some small shows for them in the past, including one for the artist Frank Stella. I organized some of his lithographic prints from the 1960s in a similar, much smaller show a couple years ago. As for future plans, I’m currently working on a book about artists who worked with NASA in the 1960s, and I’m co-producing a documentary film about NASA in the Virgin Islands in the 1960s.

“Loose in Some Real Tropics” is on view until March 26, 2015 at Cantor Arts Center.

Contact Eric Huang at eyhuang ‘at’ stanford.edu.