“Promised Land: Jacob Lawrence at the Cantor, A Gift from the Kayden Family” showcases a diversity of works by Jacob Lawrence, one of the most prominent voices in the artistic portrayal of the African American experience. This diversity is seen in the media Lawrence experimented with, the various paintbrush and pencil styles he used and the number of pieces in each series of work. All these are strung together by the appearance of the black American. The consistent theme of the black experience in 20th century America reveals Lawrence’s experience growing up in Harlem and witnessing the civil rights movement in the 1960s. At the same time, Lawrence’s works are a celebration of labor and struggle and express his hope for a progressive and equal society.

The exhibition at the Cantor first takes viewers through narratives about the African American struggle, told through multiple pieces of work. “The First Book of Moses, Called Genesis” is a series of eight silkscreen prints depicting the events of Creation, while “The Legend of John Brown” is a series of 22 silkscreen prints that explores the life of the controversial abolitionist. Both series were commissioned when their original painting versions became too fragile for display. What followed was a two-piece print titled “New York in Transit,” a replica of the mosaic mural Lawrence designed for display at Times Square Station in New York City. In a recognizable Lawrence style, “New York in Transit” is colorful, bold and bustling.

What is unique about Lawrence, though, is his ability to pack multiple themes and narratives not only in series of works but in individual pieces as well. Using different combinations of watercolor, graphite, gouache and tempera, Lawrence conveys a backstory, a plot and his message all in a single piece.

“Ordeal of Alice” shows a young African American schoolgirl surrounded by subhuman creatures in bold contrasting colors that speak of loud, domineering and violent discrimination. She is pierced with arrows, symbolizing the pain being inflicted on black children by the ongoing resistance against racially integrated schools in the 1960s. The curved lines framing the image allude to a nightmare, allowing the viewers’ imaginations a space to think further.

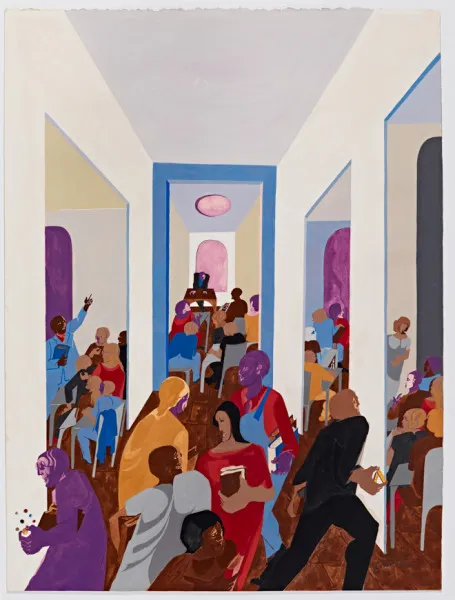

Another significant piece on display is “University,” a colorful, energetic piece that communicates Lawrence’s utopian ideal of a democratic institution of higher learning where all ethnicities are equally and actively engaged in learning. Similar to his other pieces, the human subjects in this piece are not constituted of colors filling in linear outlines, but are almost “generated” from colors, referencing how African Americans were seen as “colored” individuals. The builder figure in the middle of the painting, who has books tucked under his arm, catches the viewer’s eye immediately. While Lawrence celebrates labor in most of his pieces, the idea of social mobility and progress is further pushed here with education and construction coming together.

“Promised Land” serves as a testament to the struggle of the African American community in the 20th century. Lawrence painted his childhood heroes, the happenings he witnessed while growing up and his hopes for an open, equal and progressive society. Visitors to the exhibition can be promised a treat for the eyes and food for thought through the vivid narratives displayed.

“Promised Land” is on view until August 3 at the Cantor Arts Center.

Contact Bao Jia Tan at baojia ‘at’ stanford.edu.