When Cal baseball head coach David Esquer steps into the visitors’ dugout at Sunken Diamond on Tuesday night, he’ll be looking across the field at the classic cardinal and white pullover jerseys that he donned 30 years ago.

One of these jerseys will be donned by his lifelong mentor, Mark Marquess.

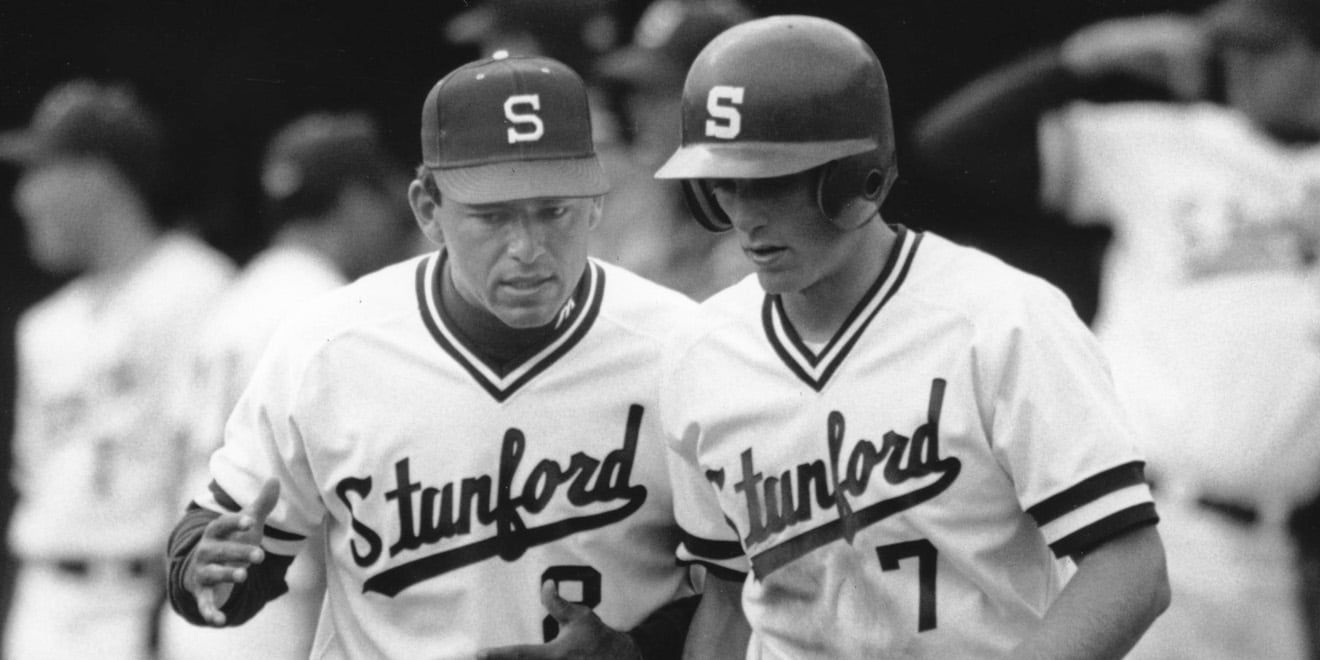

Esquer, currently in his 16th season as the head baseball coach at Cal, has strong roots on the Farm. He graduated from Stanford with a bachelor’s degree in economics and then earned his master’s in organizational behavior and was a student-athlete during the most exciting time in the baseball program’s history. As a senior in 1987, he was the starting shortstop on the Cardinal’s first NCAA championship team.

After a four-year stint in the minor leagues with three different organizations, Esquer returned to Stanford as an assistant coach under Marquess, his former head coach. He spent six seasons as Marquess’ assistant and combined with his four seasons as a player for 10 in total under “Nine,” Marquess’ nickname stemming from his longtime jersey number.

“He used to tell me he treated me like a son, but then he’d always say, ‘I’d better not say that, it makes me seem too old. I treat you like a younger brother,’” Esquer said. “He really did take an interest and invested in my development as a person and a player.”

“I remember having as many personal talks about life and we’d just be emptying trash cans around the field as I do him talking to me about how to coach players. And I know he was a person that I counseled with any job that I’ve taken and from getting married to having my first child.”

Esquer’s playing days under Marquess were tumultuous to start. He only had 45 plate appearances of his first three seasons at Stanford, as he was relegated to a backup role behind a host of star players. During his freshman and sophomore years, Esquer was behind an All-American double-play combination of shortstop John Verducci and second baseman Pete Stanicek. In his junior year, a freshman named Frank Carey won the starting job at short.

Entering Esquer’s senior season, the odds of him getting consistent playing time were also in question. Another freshman, Troy Paulson, who was the Orange County Player of the Year in his senior year in high school, threatened Esquer for the starting job at short. But Paulson went down in February with a season-ending injury, which Marquess recently recalled was the only reason that Esquer first got regular playing time.

When Marquess was asked by The Daily in 1987 how Esquer earned his way onto the field, the coach extolled his shortstop’s work ethic as the primary reason for his promotion.

“It’s what you like to see — a young man who [tries] hard and just made himself an outstanding player. He’s been a utility player for three years, but all those hours — nobody works harder than David. We practice for three hours, he stays out for another hour and a half; he’s done that for three years.

“Then he gets his opportunity, and yet it’s [still] not given to him. He has to beat out a talented freshman… Most kids would have given up.”

Recently, Marquess said that perhaps it was even better for Esquer that he wasn’t as talented as some of his infield teammates early on. He noted that, as someone who needed to prove something, Esquer needed to learn to work the hardest and that these lessons were especially important for him in his transition to coaching — he understood the process of players who weren’t always in the spotlight.

Esquer didn’t waste the opportunity he was given in his last year on the Farm. He hit .318 with 41 RBIs, 47 runs scored and 28 stolen bases in 68 games in 1987. Esquer showed up when it mattered most as well: He earned all-College World Series honors after hitting .350 with 6 RBIs, leading the team as the Cardinal won their first ever national championship.

Perhaps one of the key reasons why Marquess later hired Esquer as an assistant coach was because of this persistence, which was exemplified when he told The Daily back in 1987, “I always thought maybe I was a little weird, because I just like to practice.”

And so the tutelage continued when Esquer returned to the Farm in 1991. In a sense, though he had already graduated with two

degrees from Stanford, Esquer came back to earn a third while coaching under the mentorship of one of college baseball’s greats.

“Nine felt like he could push me as hard as a coach as he did as a player,” Esquer said. “Had I been a total stranger, maybe he was going to try to be polite and nice. He didn’t pull any punches, and I always felt like he was trying to make me a better coach just like he was trying to make me a better player.”

After six years at Stanford, Esquer moved on to Pepperdine for three seasons before he accepted his current job at Cal. Despite now being rivals with his former coach and colleague, he cherishes the deep relationship he shares with Nine.

“I tell a lot of my former teammates that I’m so fortunate…that I know a side of him that not everyone gets a chance to,” Esquer said. “He’s as good a family man, as strong a Christian, as humble a person as anyone would think. A lot of people get the wrong impression — think he’s a little aloof because he feels almost cocky — but it’s wrong.

“One of the reasons why I went into coaching was when I saw that having a family and being a good family person while doing it was possible, then I said I would do it. Coaching can be really hard on your family, and if it was full of divorce and broken families, I didn’t want to be a part of it. But the example he led for me — it can be done.”

The master and now extremely accomplished apprentice will clash again when the Cardinal and the Bears meet on Tuesday night. Even though they have been facing each other for 16 years, for both coaches, things are different when they see each other in opposite dugouts.

“You want to win as bad as you were competing against your own brother,” Esquer said. “I learned that here — that sometimes you compete more fiercely against your own family than you do against a total stranger.”

“It’s much more difficult to compete against people you know and like. You would like to be able to dislike him — it’s easier to try to beat them if you dislike him,” Marquess said. “You might like to beat your brothers and sisters, or whatever it is, especially when so much is riding on it. Nowadays, if you don’t win enough games, maybe you get fired. And that affects your family.”

Contact Jordan Wallach at jwallach ‘at’ stanford.edu.