*Glenn Wilson is a pseudonym used to protect the identity of the subject of the story.

In June 2013, Glenn Wilson*, a graduate student in the School of Engineering, walked outside his Escondido Village apartment to find his 3-year-old daughter playing in lead paint chips that University officials told him “weren’t harmful.”

He spent the next two years trying to get Stanford to take responsibility for exposing Escondido Village residents and dozens of construction workers to dangerous amounts of lead. Instead, Stanford downplayed the extent and risks of resident exposure and rehired the companies involved in the incident, according to an investigation by The Stanford Daily.

‘Chunks of paint, just, everywhere.’

Before the ’70s, lead-based paint was in high demand across the United States. Its density made the paint easier to use than oil-based alternatives, and lead paint was endorsed by the United States government up until 1978, when it was discovered to be a major health hazard. By that point, lead paint was ubiquitous — so much so that the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continues to warn homeowners that homes and condominiums built before 1978 are likely to be painted with lead paint.

According to the EPA, undisturbed lead-based paint poses no health risks. However, health concerns arise as soon as the painted surface is disturbed. Even a surface scratch could lead to paint chips flaking off the wall, leaving residents exposed to dangerous amounts of lead. Health risks include behavioral and learning problems, nerve disorders and seizures. In 1991, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services called lead paint the “number one environmental threat to the health of children in the United States.”

Wilson, a 20-year veteran of the construction industry, was all too familiar with the dangers of lead paint exposure. In one of his earlier jobs as a union laborer, Wilson witnessed his coworkers sandblasting lead-based paint off a steel bridge. He said that their project manager was not wearing proper respiratory equipment, as mandated by the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Association (OSHA) for all lead paint stripping projects. Less than half a year later, the project manager passed away from medical problems tied to lead poisoning.

In 2009, Wilson was accepted to a Stanford graduate program and was assigned housing in Escondido Village (EV). Upon moving in, Wilson said, he was handed a federally mandated notice from Student Housing detailing the presence of lead paint in residences.

Wilson was concerned about the possibility of living in a lead-painted residence with his wife and his young children, but his concerns were soon set aside as he focused on his graduate research.

Five years later, in the summer of 2013, Residential and Dining Enterprises (R&DE), the University auxiliary that runs housing and dining, began a long-planned renovation project in Escondido Village. Part of the renovation project involved San Jose Construction (SJC), an R&DE contractor, stripping lead paint from 42 EV buildings.

Multiple EV residents said they were not informed of the potential for dangerous lead paint dust or told to take any precautions.

During the renovations, workers sealed windows and doors with plastic sheeting, but residents said that the sheeting was not particularly effective, with construction dust still making its way into residences. To complicate matters further, according to multiple residents, it was an unseasonably warm period, with temperatures regularly breaking 100 degrees. Some EV residents, having not been made aware of the lead paint stripping by Stanford, tore open the sheeting in an effort to bring fresh air into their apartments, which did not have air conditioning.

Wilson remembered a particularly hot day at a friend’s apartment when he realized the risks posed by the construction. Like many in EV, the friend had poked holes in the plastic sheeting on his windows in an effort to counter the heat. Wilson said that much of the apartment was covered in a fine layer of construction dust, as were most common areas outdoors. He thought back to the 2009 notice detailing the presence of lead paint and was suddenly ill at ease.

“It was like postage-stamp chunks of paint, just, everywhere,” Wilson said.

The lead paint that killed his project manager was now lying on his doorstep, on his friend’s kitchen table and on the playground equipment used by his 3-year-old daughter.

During any removal of lead-based paint, the remover must continually dampen contaminated surfaces to avoid allowing lead-based particles to escape, according to the California Code of Regulations, the state law that covers lead paint safety. The Code’s Title 8, Section 1532.1 states that employers “shall prohibit the removal of lead from protective clothing or equipment by blowing, shaking or any other means which disperses lead into the air.”

Contractors, however, pressure-washed old paint off the buildings in Escondido Village, spreading lead-based paint chips across EV and coating apartment interiors in a layer of dust. The dust covered Wilson’s belongings, his toddler’s high-chair and the table at which they ate every meal, despite the plastic sheeting.

On June 26, 2013, Wilson sent an email to Stanford Housing detailing his concerns of the lead paint dust hazard. Housing did not respond. Almost two years later, Stanford has yet to take action against those responsible for the incident. To this day, Stanford continues to use the same painting contractors for other projects.

“At no time was there a threat to the health and safety of residents at Escondido Village from the summer 2013 painting project,” said Lisa Lapin, University spokeswoman, in an email to The Daily.

Responsibility in the subcontracting process

In order to provide the best quality work on larger construction projects, the general contractor will often subcontract out portions of the work to companies that specialize in a particular area of construction. Subcontracted work ranges from electrical wiring to paint removal and reapplication. In the process of dividing up a job, the responsibility for completing the work both adequately and safely passes to the Project Manager of the subcontracted company.

For the Escondido Village renovation project, R&DE contractor SJC subcontracted the stripping, disposal and repainting work to Sunnyvale-based Monroe Painting.

On July 1, Wilson contacted the Santa Clara County Department of Health (SCC-DOH) and left a message for the Senior Environmental Health Specialist, Lisa Flores, who never called him back. The Daily confirmed this with Flores, who remembers never returning the call.

On July 29, Wilson followed up with SCC-DOH and reached out to Cal OSHA, the local arm of the federal agency responsible for ensuring compliance with the laws regulating the use of lead paint. OSHA received the following complaint of hazardous working conditions at Monroe Painting: “Employees are scraping off lead-based paint without wearing any protective equipment. Paint chips are on the ground and are not disposed of properly.”

Meanwhile, Monroe Painting continued to power-wash lead-based paint off buildings without protective equipment.

On July 31, 2013, OSHA had still not responded to Glenn Wilson. After calling dozens of Stanford administrators with no response, Wilson submitted a HelpSU in a half-exasperated, half joking last-ditch attempt to provoke a response from the University. Eventually, Kip Fout, Stanford’s Asbestos & Lead Health Program Coordinator, who works in the Environmental Health and Safety (EH&S) department, responded. EH&S is responsible for minimizing safety, health, environmental and regulatory risks on campus. The department is tasked with overseeing every construction project on campus and has rigorous contractual standards.

Fout found what Wilson had been claiming all along: construction crews had power-washed the building exteriors, in violation of EH&S regulations. EH&S issued a stop order and sent an abatement crew, Restoration Management, to clean up the toxic debris created by Monroe’s workers.

“We don’t perform a lot of sampling for lead,” Fout said. “We’re overly protective. We presume everything has lead.”

If a contractor doesn’t want to treat paint as containing lead, Fout explained, they have to prove that there’s no lead in it. According to Fout, Monroe Painting violated their contract.

Monroe Painting did not respond to requests for comment.

Health concerns and workers’ rights

Glenn Wilson was suspicious that Stanford would neglect to take the issue seriously enough to take proper steps to clean up the toxic damage. On July 7, 2013, Wilson and a friend collected samples from soil and sand around Escondido Village residences to submit for lab testing for lead contamination.

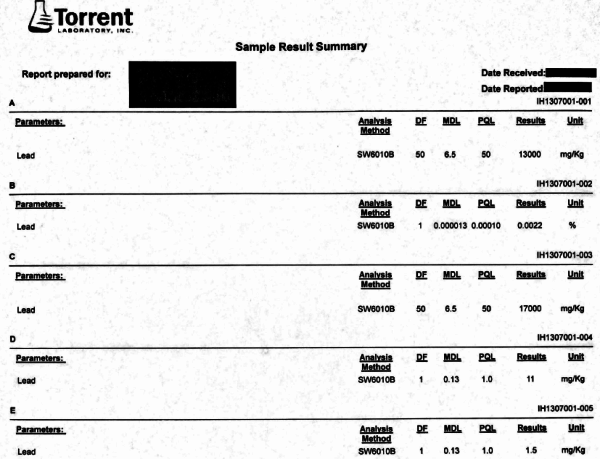

On July 9, they sent five samples to Torrent Laboratory to test for lead contamination. Three weeks later, the test results arrived in the mail. Two of the five tests came back positive for hazardous waste, showing lead levels above 1,000 mg/kg. In smaller concentrations, traces of lead were found in all five soil samples.

Even the smallest incident of lead exposure carries health risks. In emails sent to EV residents on Aug. 14, Donald Smith, Environmental Toxicologist at the University of California Santa Cruz, wrote: “The CDC has done away with a ‘threshold of concern’ approach in light of the evidence showing measurable effects on cognitive function in children with blood lead levels well below 10.”

After seeing the results of the lab testing, Wilson and his friend wrote separate emails to Student Housing urging the department to take the incident seriously. “The levels of lead are demonstrably hazardous, and it is clear that the chips have been scattered throughout the area, both visibly and invisibly,” wrote his friend. Their emails cited previous communications in which Housing had dismissed the issue. Four days later, a Housing Associate responded to the pair’s concerns by explaining that nothing could possibly be amiss, because “the workers would be doing abatement if the paint were dangerous.”

Unaware of their exposure, workers would return home to their families in the evenings coated in a toxic dust.

Troubled by Stanford’s lack of reaction, Wilson reached out to the Stanford’s Student and Labor Alliance (SALA), an organization devoted to protecting the rights of support workers on campus. Despite years of experience working with Stanford administrators, SALA was also unable to obtain a satisfactory response from the University.

Even if they are aware of hazards on the job, workers often find it impossible to exercise their right to a safe workplace out of fear of losing their job, retaliation by their employer or, if they are undocumented, being discovered and deported. According to Andrea Hale ’15, a member of SALA, such fears are common to workers on campus.

“My understanding is that if you speak out about something… you’ll just be fired, for whatever other reason,” Hale said.

Fout explained that the painters placed at risk were employees of Monroe Painting, SJC’s subcontractor. Because Stanford did not directly employ Monroe Painters, Fout said, the University had neither the power to follow up with workers nor the legal authority to require workers be tested for lead exposure.

Cleanup

Under Fout’s direction, EH&S initiated an immediate cleanup of Escondido Village, contrary to Student Housing’s initial stance that nothing was amiss.

Wilson and his daughter watched from their backyard as the abatement “outside contractor” crews picked up lead-based paint chips — some of them with their bare hands — from the public open spaces of EV.

Fout explained that no license is required to clean up lead-based contaminants, and the decision to provide workers with personal protective equipment is based on an exposure assessment done by the company contracted to do the abatement work. In this case, he said, “the risk of exposure picking up paint chips is relatively low.”

On Aug. 2, 2013, Residential and Dining Enterprises finally announced the lead exposure — and R&DE’s cleanup efforts — in an email to EV residents:

“It has been brought to my attention by some thoughtful residents that the actions of a painting contractor in Escondido Village may have disturbed some older paint,” wrote Mike VanFossen, who was, at the time, the Project Manager from Student Housing overseeing the project. “Some small paint chips or flakes have fallen away from the mats laid down to catch the material on the patios, and we will be making immediate efforts to clean up that residue.”

VanFossen wrote that there was no reason to believe there had been “problematic” exposure to the lead-based paint. He cited Wilson’s test results as proof: “As further reassurance, some testing has already been done, and several of the tests came back negative.” There was no mention of the two tests that came back positive.

History of issues with lead exposure

Lead exposure has been an issue for Stanford in the past. In October 1994, Stanford paid $166,265 to settle with Sarah Dennison-Leonard J.D. ’94 and her family over a lawsuit alleging their 1-year-old daughter had been exposed to lead paint at the family’s graduate residence in Escondido Village.

The plaintiffs alleged that Stanford had violated Proposition 65, the 1986 Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act, declaring that Stanford had “failed to give clear and reasonable warning to student families residing at Stanford’s Escondido Village Housing Complex and to the parents of students enrolled in Escondido Village Childcare facilities who have allegedly been exposed to lead.”

“They denied everything,” Charles Dennison-Leonard said. “[Stanford] had galvanized swing sets but they had painted them, and that was one of the exposures. Paint was flaking off into the sand pit.” Dennison-Leonard said that Stanford had not adequately cleaned up the paint, citing Stanford’s action to change the sand in the sand pits after the settlement in 1994 without removing the swingset.

Wilson maintains that, by not responding to his complaints, Stanford violated Section 10 of the settlement agreement, which states, “Stanford agrees to inspect apartments within five working days of a report to the Escondido Village Facilities Office by a resident of peeling, flaking or bubbled paint, and promptly notify the resident of the results of the inspection in writing.”

The fallout

Seven years ago, Glenn Wilson applied to the Engineering Department at Stanford hoping to study how the construction process could better address workers’ needs. He imagined Stanford would model relationships between laborers and management and exemplify safe, responsible construction.

He never imagined his children would be exposed to lead.

Almost two years after the paint removal in EV, Monroe’s trucks still appear on campus. Wilson pulls out his iPhone and scrolls to a picture of a Monroe Painting truck. “I took this photo last week,” he said on May 7, 2015. While R&DE has the power to stop working with companies that violate rules and regulations dictated in their contract, Monroe’s trucks still appear on campus.

Fout maintains that Monroe Painting is to blame for the incident, yet the contracting process gives Stanford the power to dictate the rules and regulations construction companies have to follow. Moreover, as a private entity, the University can elect not to award jobs to contractors who regularly violate such regulations.

Glenn Wilson said he has spent the last two years trying to get Stanford to take responsibility for exposing hundreds of EV residents and dozens of construction workers to dangerous amounts of lead. Two years ago, Glenn Wilson contacted the Dennison-Leonards to ask for guidance in his dealing with the University.

“I can’t say that we were surprised, when we were contacted two years ago in 2013,” Charles Dennison-Leonard said. “The most important thing to Stanford was to deny wrongdoing and stonewall.”

“We did hope that the problem would just be dealt with instead of contained from a publicity approach. So there’s a little disappointment.”

Taylor Brady contributed to this report.

Contact Reade Levinson at readel ‘at’ stanford.edu.