For the last two years or so, the new hot tactical philosophy across all levels of football has been the run-pass option (RPO), better known as the “packaged play.” Cal runs packaged plays constantly, and it did just ring up 495 yards of offense on Stanford’s defense last Saturday in Stanford’s glorious Big Game victory, so it’s only appropriate that we discuss RPO packages today. (Glorious! Six wins on the bounce!) It’s also only appropriate that we discuss why the RPO is so controversial, because, well…cough, cough, Cal.

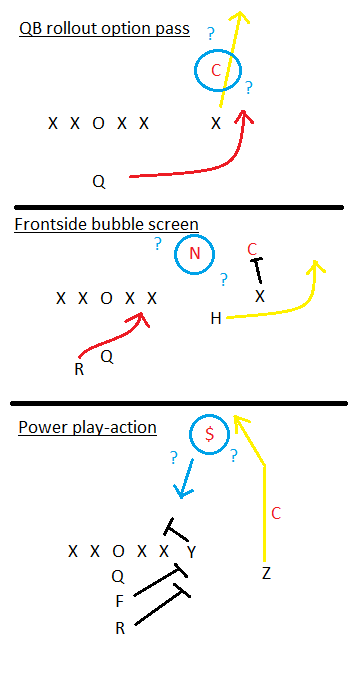

However, the rules force offenses to ultimately declare a run or a pass after the snap, and that’s why it’s easy for defenses to react quickly to an unfolding offensive play. The offensive pass interference rule bans receivers from blocking before the ball is actually thrown. And if you are going to throw the ball, the illegal-man-downfield rule is designed to stop you from committing your offensive line to the run. Ineligible receivers (99 percent of the time, this means offensive linemen) can’t be more than three yards downfield. But three yards is a lot of leeway. You can still block downfield and throw the ball, and it’ll look a lot like a play-fake.

It’s not just spread option teams that use RPOs. Run-first offenses like Oregon use RPOs, pass-first teams like Oklahoma State use them — even Stanford uses them, particularly in Kevin Hogan’s “in-case-of-emergency” QB Power package.

(Word to the wise: David Shaw is a very modern offensive coach. He relies so heavily on his base offense for two reasons: first, because his offense is so good that he can get away with it, and second, because he knows that opposing coaches can watch his game film too, so the fancy stuff should stay in the playbook and off the field as long as possible.)

Because RPOs are so popular these days, the NCAA considered giving linemen just one yard of freedom instead of three after the end of last season. Clearly, the NCAA decided that changing the rules wasn’t worth it. I wholeheartedly agree. The solution, if the situation even needs a “solution,” is to enforce the rules already on the books, and to only change the rules if the rules are nonsensical or blatantly unbalance the game.

Unfortunately, I’m also going to highlight one of the reasons why a number of people think that RPOs should be banned: because they can encourage teams to break the rules and dare the refs to throw flags on every play. I don’t like harping on about no-calls — regardless of whether Stanford wins or loses — but I saw Cal sending illegal men downfield often enough that I want to make a point of highlighting that tendency today. There’s nothing inherently wrong with the run-pass option, but I don’t think Cal runs it in a way with which I’d be comfortable.

I’m not saying that Cal got special treatment compared to other teams that run packaged plays. I am, however, going to diagram two RPOs in which Cal blockers broke the rules — and these two RPOs helped set up 10 points for the Golden Bears.

***

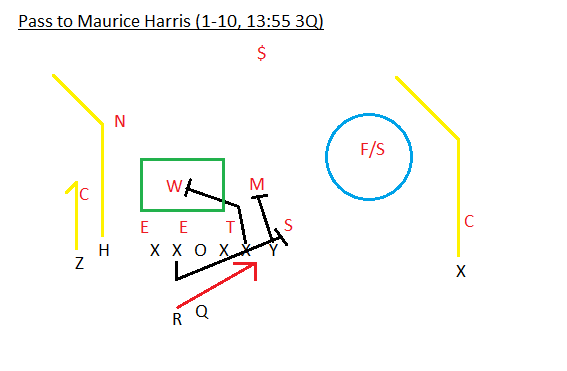

Both plays I’m discussing today are standard frontside traps with a deep post tacked on top. The backside guard pulls out of the formation and hammers the end man on the line of scrimmage, and the player that would ordinarily block the end man moves forward to block a linebacker. Both of these plays are also run in an illegal fashion, and in ways that make it considerably easier for Cal to move the ball.

Everything so far is kosher. Whitfield is trying to play two roles at once, which is a tough situation for any player. But Cal forces Whitfield to more meaningfully respect the run by blocking for a run play, which should rule out the possibility of a pass. At the snap, linebacker Blake Martinez (W) actually drops behind the magic 3-yard line when he realizes the play is an RPO, likely because anybody who’s watched Cal film can tell you that Cal…erm…toes the line…with illegal men downfield. Cal’s right tackle Deion Oliver blocks him anyway. That’s a signal for the safeties to crash the run.

Oliver isn’t flagged, Whitfield sees that Cal has its blocks set and moves towards the tackle box, and Harris (X) gets his one-on-one matchup against Alameen Murphy (C). With a star quarterback like Jared Goff throwing the ball and a 6-foot-3 wideout versus a 5-foot-11 corner, that play’s an advantage for the Golden Bears. But if Whitfield hadn’t focused on the run and instead bracketed the post route, the advantage would have flipped to Stanford. Instead Cal marched into the red zone.

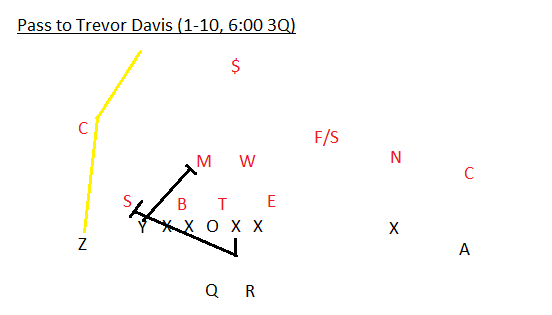

This is the same play as the previous one, but it presents an even easier read for Goff, because Whitfield is on the opposite side of the field. Goff will throw the skinny post to Davis (Z) unless Stanford shifts to Cover 2. Two high safeties would give Dallas Lloyd ($) a better angle on Davis, but it would also give Cal a six-on-six matchup in the box, making a run play more viable. (Strictly speaking, it’s already six-on-six, but Whitfield can recover to the box if Cal runs the ball.)

Again, everything is legal until the snap. But after the snap, tight end Raymond Hudson (Y) makes contact with linebacker Jordan Perez (M) when Goff still has the ball in his hands, and five yards beyond the line of scrimmage to boot. (Even if it had been four yards, the NFL five-yard contact zone does not apply to college football.) This isn’t an ineligible receiver downfield penalty, as Hudson is perfectly eligible, but it is offensive pass interference.

With Davis one-on-one with Terrence Alexander (C) and Lloyd too far away to provide meaningful safety help, Goff finds a window and gets Cal to the Stanford 5. Cal would have gotten eight yards easily if Dykes had just called a trap, but the post was more enticing.

The skinny post was the right call at the right time, and in this case, Stanford’s defensive back alignment ($ deep, as usual, and F/S shifted to the wide side of the field) played into Cal’s hands. The run-pass option element of this play was essentially nonexistent. I get why referees might be loath to throw flags on a play that would have been successful with or without the penalty — you can argue that Lloyd would have been able to react quickly and bracket the post if Cal’s line had pass blocked instead of trapping, but at the end of the day, this was just a good call by Dykes. But this fact raises the question: Why not just run a standard play instead of stretching the rules? Ultimately, the way Cal ran this play is a symptom of a larger problem with how Cal chooses to run its offense.

***

I’ve just criticized Cal and Sonny Dykes, so let’s be fair to Dykes. If I said this to his face, he’d likely ask in response: If a play is chronically no-called, is it really a rule?

We all know about the Seattle Seahawks playing tough press coverage with their cornerbacks, daring referees to call defensive pass interference, and we all know about the New England Patriots doing the same with their receivers on the offensive side of the ball. But many fans may overlook the extent to which rules are stretched on every single play. At the very least, they may overlook stretching the rules when it comes to their own team.

A lot of Stanford fans appear to have ignored Stanford holding on Christian McCaffrey’s magnificent kickoff return touchdown — although that TD falls under the same category as the Trevor Davis reception, where the illegal act had no direct effect on the outcome of the play. And for the most part refs are pretty generous with the rules too. I’d say that most holding isn’t called — and when it’s flagged, it’s often after one or two warnings by the refs. In that case, limited holding becomes in a strange way acceptable.

Moreover, even if Cal broke the rules, its wideouts still had to get open. Goff did most of his damage against soft zone coverage (David Shaw hates the term “bend-but-don’t-break” because it sounds “passive,” but if Stanford’s gameplan on Saturday wasn’t bend-but-don’t-break, nothing is), but Harris and Davis got open against what amounted to man-to-man coverage. They did their jobs. They got open. It’s not as though RPOs are guaranteed touchdowns. You still have to work for your points; you just have to work less.

Nevertheless, Cal made hay out of sending guys downfield and never got penalized for the privilege at all. Cal picked up 8 penalties for 63 yards, but look at the play-by-play for yourself — not a single one of Cal’s penalties involved illegal blocking in the tackle box, and yet that kind of blocking was an important component of Cal’s offensive scheme.

Sure, Stanford won. And sure, it might not be sporting to point out Cal no-calls in a game that Stanford won. I’ll admit that I’d be able to sleep at night if Stanford were the team running illegal run-pass options in its base offense — if the team was chronically not flagged, it might as well be legal. But at the risk of sounding sanctimonious, I’m still not a fan of what Cal’s trying to do, because it’s against both the letter and the spirit of the rules. And while pushing the boundaries of what we normally expect is part of football, I think Cal can do better. The Pac-12 can start by throwing some flags.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.