What a game.

Goodness gracious, what a finish. Thirty seconds and three timeouts, with Stanford stuck on its own 27-yard-line? No problem.

The thing about wins like these is that when all is said and done, you can easily point to the reasons why Stanford defied the odds to beat then-No. 4 Notre Dame on Saturday. Notre Dame hadn’t really stopped Stanford all night. A blitz-happy Fighting Irish defense was always getting close to Kevin Hogan, but Hogan was not rattled. Notre Dame’s secondary, depleted by injuries, was particularly weak down the middle – and Devon Cajuste had set the Irish on fire the entire game. Also, the prevent defense isn’t really a great play when you stand to lose with a field goal. Was it really that inconceivable that Stanford could connect on a couple long throws against soft zone coverage?

But even though hindsight is 20/20, that insight doesn’t change the fact that most people – myself included – thought the Fighting Irish were going to win the game. Well done, Stanford.

***

Let’s take a look at the 27-yard completion to Cajuste that got Stanford within field goal range. One thing I don’t think we could have predicted was that ND defensive coordinator Brian Van Gorder was going to do utterly un-BVG things with the game on the line. Brian Van Gorder blitzes. It’s what you pay him to do.

So why was Van Gorder running a prevent defense on Notre Dame’s last stand? The prevent defense is terrible. Moreover, it’s a passive defense, which is not very Brian Van Gorder. Last year Van Gorder stopped Hogan cold on Stanford’s last-ditch drive with a daring blitz. This year Van Gorder blitzed and blitzed…until the game was on the line. (Check out the video here.)

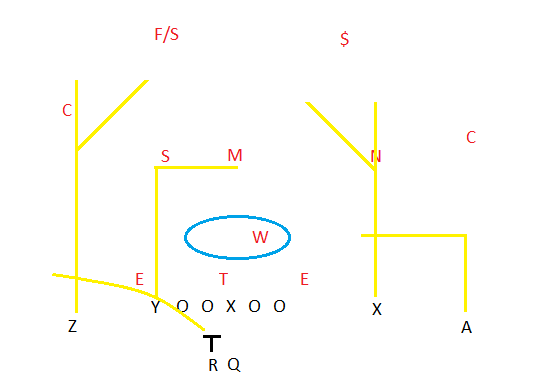

First off, let’s look at the players that opened things up for Cajuste (X) down the middle. McCaffrey (R) doesn’t do very much on this play (he just checks for a blitz and releases to the flat), but he distorts Notre Dame’s defense right at the start. Notre Dame drops linebackers Jaylon Smith (S) and Joe Schmidt (M) deep to cover Austin Hooper (Y), first because Hogan is well known for his chemistry with Hooper, and second because if Stanford ran an RB screen for McCaffrey on the left, Stanford would pick up about 15 yards easily unless ND devoted that extra man to Hooper. But when you have four guys around the pocket and two safeties deep, and then put two defenders on Hooper, there’s only three men on the other three receivers. And it’s a little difficult to stop Cajuste one-on-one when he’s got a full head of steam.

Cajuste’s route is dictated by the defense: He runs up the field against Cover 2 (a middle-of-the-field-open “MOFO” read) and heads upfield against Cover 1 or Cover 3 (middle-of-the-field-closed/“MOFC”). The route name is instructive. It’s formally called a seam route. Some West Coast offense coaches just call it “win.” Win your matchup and run towards space. After the game, Cajuste told me that all he was thinking about during the play was how he could “bend the route” – the middle of the field was open, so that’s where he ran.

After the snap, no deep pass is easy, but this one was easier than most. Van Gorder clearly does not trust nickelback Matthias Farley (N) and his safeties – in other words, the defensive backs that patrol the middle of the field, where Cajuste has historically done the most damage. Notre Dame is giving Cajuste massive cushions even before the play begins. And in the prevent, ND’s backfield is so spread-out that if Hooper could hold ND’s linebackers 10 yards deep on his dig route, Cajuste is going to get open behind them. ND is also setting up the defense so far down the field that Cajuste can hit top speed.

Free safety Max Redfield (F/S) focuses on the route on the left sideline. Strong safety Elijah Shumate ($) messes up in coverage; since Farley is playing with outside leverage and funneling Cajuste inwards, Shumate needs to aggressively cover Cajuste on the inside, and doesn’t. For his own part, Farley gives Cajuste too much space and Cajuste adjusts by breaking inwards a little earlier than Farley expects.

“We got to close down inside-out on that seam route,” Notre Dame head coach Brian Kelly admitted after the game. “I thought we probably played it a little bit too much outside-in, worried about backing up. We got to be more aggressive to a seam route.”

With space, Hogan and Cajuste made the play look easy. “I didn’t even see the ball coming,” Cajuste explained. That’s chemistry right there – that’s the legacy of five years of practice for the Hogan-Cajuste duo. Hogan hit Cajuste in stride 14 yards deep and Cajuste dragged Notre Dame defenders down the field for another 13. Two plays later, Conrad Ukropina sank Notre Dame’s national championship hopes.

All credit to the Fighting Irish. They battled through a lot of adversity and somehow got to No. 4 in the country. They were a great team, with a dominating offense and (for most of the season) a very solid defense. Notre Dame huffed, and puffed, and when it was about to blow the house down it decided to run the prevent defense.

Both teams deserved to win the game. But only one team could, and it ended up being the one that wasn’t giving Devon Cajuste massive holes in zone coverage.

***

Some points on David Shaw’s decisions at the end of the game.

During the game, I’ll admit that I was utterly shocked by – if not apoplectic towards – Shaw’s decision to hoard his timeouts on Notre Dame’s clock-killing final drive. Shaw said that the coaches talked about what to do with the TOs, and decided that they were going to ride or die with the defense. Somehow Stanford got away with it.

It became increasingly clear with hindsight that:

1) Even if Shaw was rightly confident in Stanford’s red zone defense, not calling timeouts was excessively risky. To be fair, Stanford’s red-zone TD allowed percentage is 44 percent, which is otherworldly. And ND has had red-zone problems all season long. But that TD percentage is artificially depressed by the fact that most teams are operating on three downs on offense. For Notre Dame, it was TD or bust, and Brian Kelly was working with four downs. Moreover, it was clear that Notre Dame was not going to be limited by the clock – it had two timeouts left on its final drive. Notre Dame was methodical on offense even in the final minute of the game. Stanford was not going to win by forcing Notre Dame into a hurried, last-ditch prayer to the end zone. The Irish have a fantastically well-drilled offense – and they are going to be downright terrifying next season.

2) To be fair to Shaw, calling timeouts on defense would have imposed a very real opportunity cost on the offense. Shaw wanted to save timeouts in order to throw posts and seams into the middle of the field, because that was where the big-play opportunities were – and first downs down the middle like Cajuste’s win route in crunch time don’t stop the clock for very long. Moreover, throwing deep down the middle is easier than throwing deep down the sideline. It’s fair to say that Shaw’s decision-making, though perplexing, made some sense. That doesn’t mean that Shaw made the right decisions, but these decisions weren’t baseless either.

If you want to complain about a coaching decision, I’d say that Shaw’s decision to run Christian McCaffrey up the middle on Stanford’s penultimate play was the real shocker. McCaffrey did a great job on Saturday of grinding out yardage, even when the yards weren’t blocked for him, but running up the middle is rarely a recipe for a solid gain. Even Power, Stanford’s signature play, is off-tackle. Just because Ukropina converted a 45-yarder doesn’t mean that his odds of success wouldn’t have been much higher if he had been kicking a 35-yarder instead.

But I don’t know who made the call on that play. It might not have been Shaw. The decision is more complicated than you might expect.

The best way for Stanford to pick up yardage would likely have been speed out routes, and at the very least, Stanford could have taken more time to gauge how much of a cushion Notre Dame was giving Stanford’s wideouts on the outside. But completing out routes would have forced Ukropina to kick the ball from a hash mark. Running the ball up the middle was the only way to guarantee that Stanford would center the field goal attempt. And if the kicker wants the ball in the center, he gets the ball in the center. I’d have preferred a slant route if Stanford was going to center the ball. But all in all, if Stanford handles kickers like many football teams, the decision to center the ball or go for extra yardage would ultimately have been Ukropina’s to make.

Contact Winston Shi at wshi94 ‘at’ stanford.edu.